NEWS

NEWS

NEWS

NEWS

NEWS

NEWS

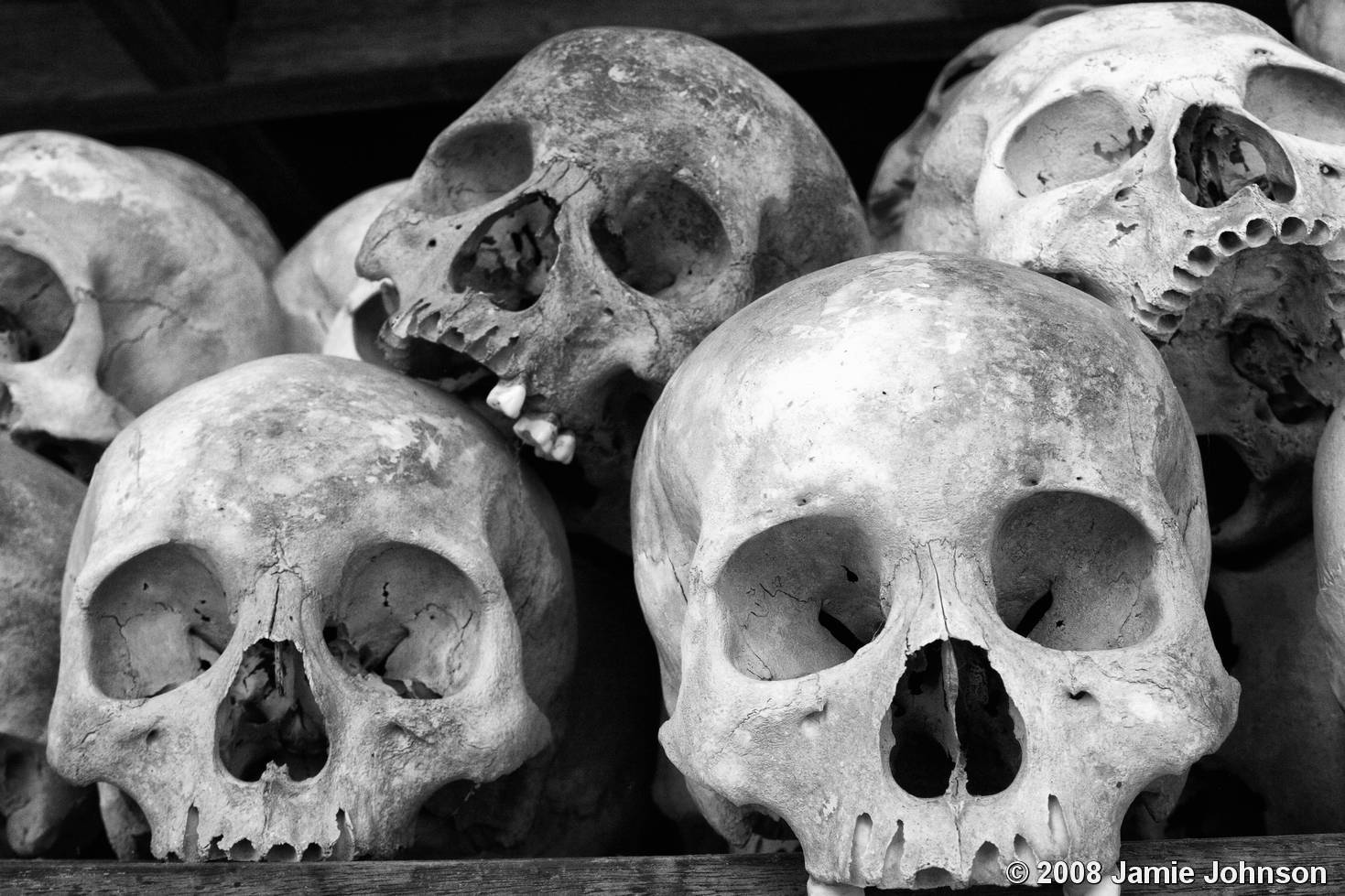

![]() Back in 1945, when Allied forces finally overrun Nazi Germany and the full horror of the Holocaust was revealed, the leaders of the world’s democracies vowed that genocide on this kind of scale would never happen again.

Back in 1945, when Allied forces finally overrun Nazi Germany and the full horror of the Holocaust was revealed, the leaders of the world’s democracies vowed that genocide on this kind of scale would never happen again.

What hollow words they were.

Since then, we’ve witnessed at least half a dozen more genocides where over 100,000 people were killed. These include the expulsion of Germans from occupied countries after WWII, the partition of India, the Cambodian Genocide, the Bosnian Civil War, the Rwandan Genocide, and the current Darfur crisis. Indeed, the systematic murders in Darfur continue to this day, whilst in Syria, President Bashar Assad and the rebels are well on the way towards racking up a similar score.

It’s not that people haven’t tried to prevent these genocides from taking place. Various organizations, such as Genocide Watch, United to End Genocide, and the Genocide Prevention Program, have been founded in the last two decades to try and stop mass-murders of this kind, but for all their good intentions they simply haven’t had the means to end the violence.

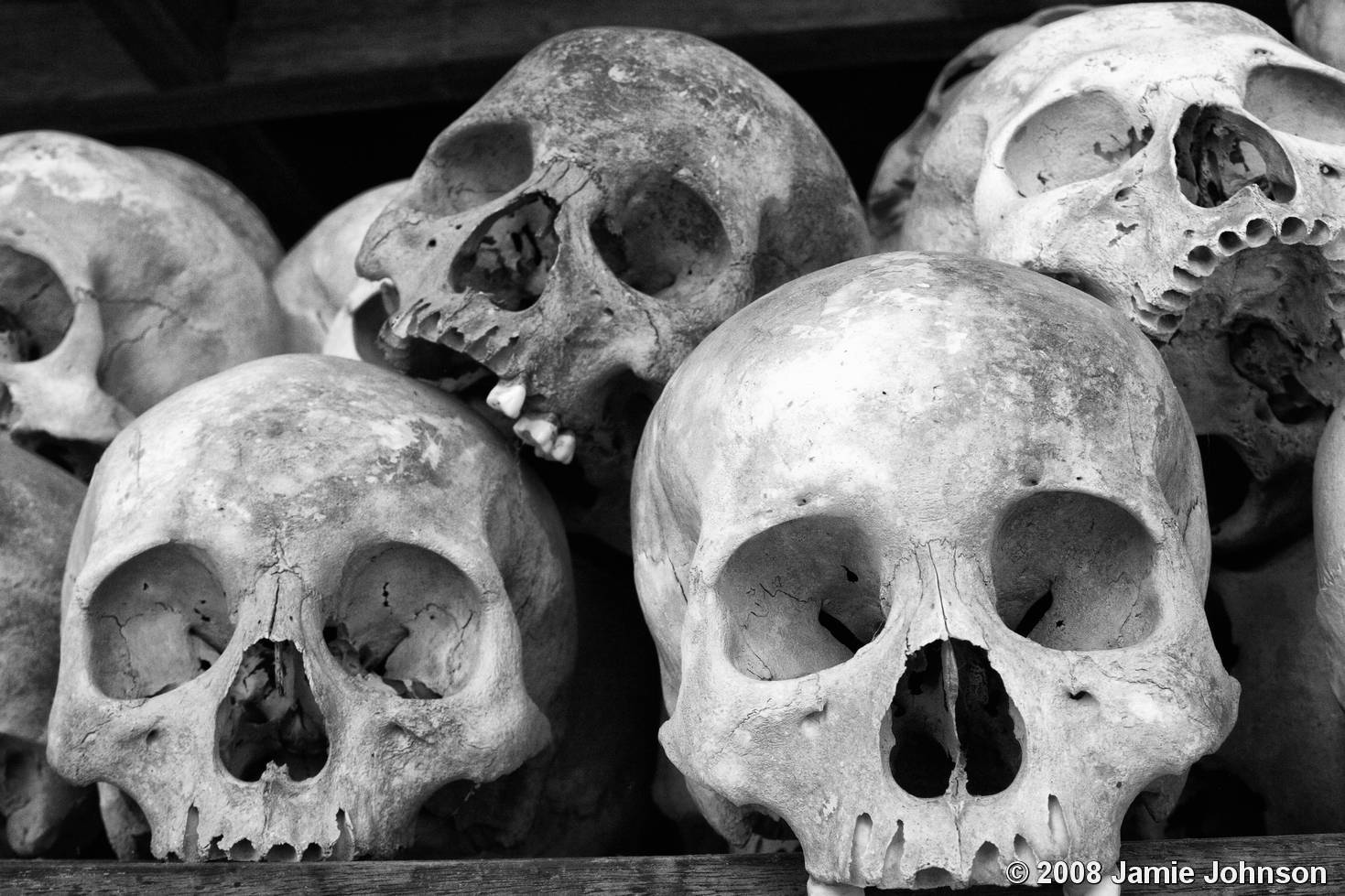

![]() Is there any chance for technology to succeed where good intentions have failed? That’s precisely what the latest anti-genocide group likes to think, and it’s been attracting plenty of buzz since it announced itself last month.

Is there any chance for technology to succeed where good intentions have failed? That’s precisely what the latest anti-genocide group likes to think, and it’s been attracting plenty of buzz since it announced itself last month.

The Sentinel Project, a Toronto-based NGO, has hit on the novel approach of using Big Data in order to try and spot the early warning signs of genocide, so that governments and international agencies can take action before the killing starts. To do so, its setup a revolutionary hate-speech tracking database, called Hatebase, to monitor the occurrence of hate-fuelled language around the world.

Hatebase is like an urban encyclopedia for the uninitiated, made up of a vast collection of abusive slurs and terms corresponding to race, religion, class, disability, sexual orientation and gender. The database includes information on which language(s) the terms are spoken in, the countries where they’re used, and their meaning.

What Hatebase is trying to do is to encourage people to sign up and report any incidents of hateful speech in their areas, in order to discover trends that could indicate ethnic violence is about to take place. People are encouraged to report anything directed against them, or anything they witness, that could be considered “hate speech”. In addition, people can also report websites, radio stations and other forms of media that promote hatred.

Hatebase maps incidents of hate speech around the world

The idea is that action can be taken when these trends start to sound alarm bells. In theory, there’s every chance it could work, even if the concerned governments don’t do anything to prevent the killing. NGOs for example, could use the information to try and counter websites promoting hate, or else they could warn communities that are at risk, using the data to direct target groups to ‘safe areas’.

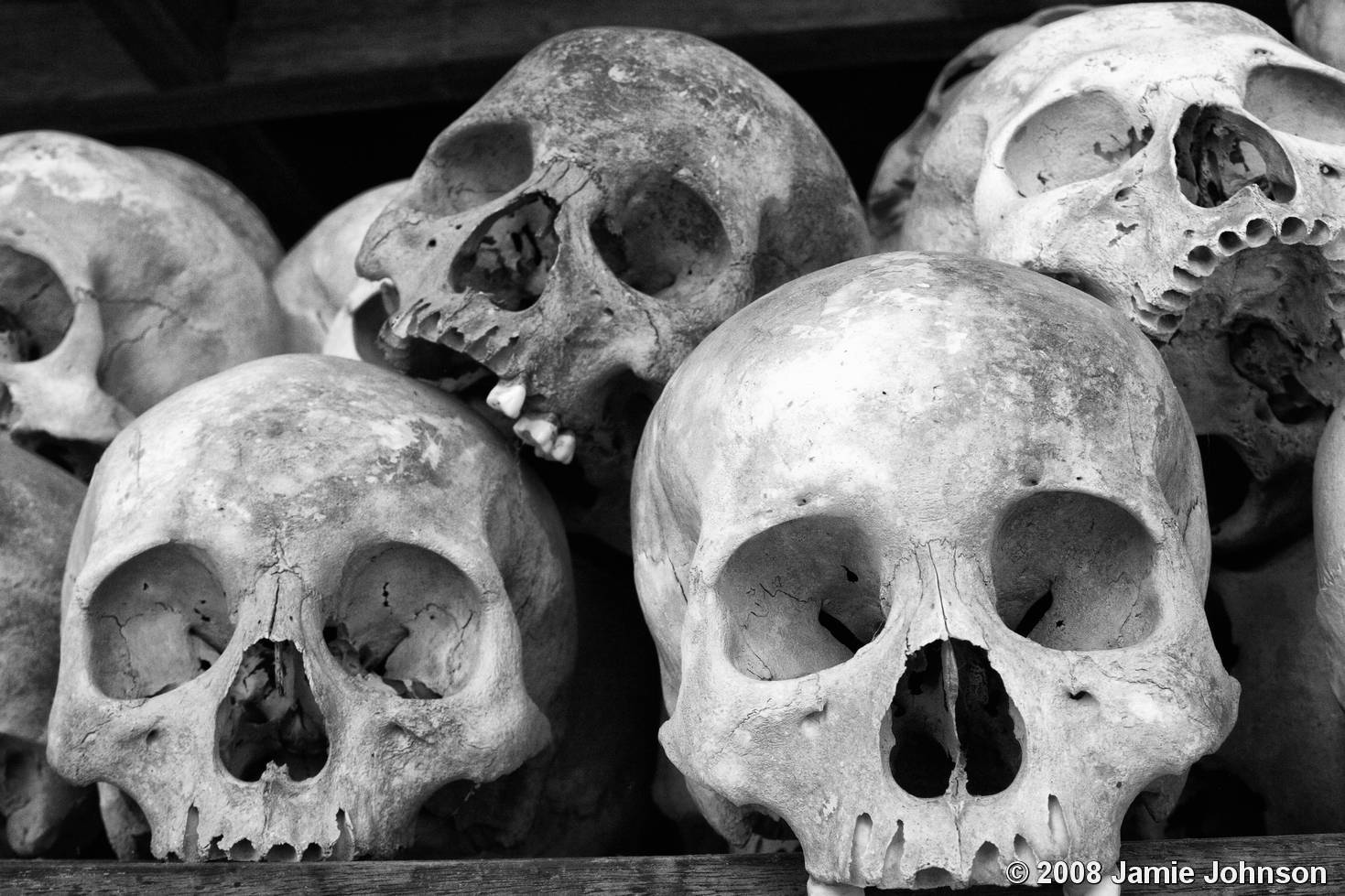

![]() Genocide Watch has outlined a guide to genocide, the so-called “eight stages of genocide”, which states that mass murder inevitably begins with the “classification” and “symbolization” of a target group. Classification refers to the split or separation of “us from them”, while symbolization represents the name calling once that split has occurred. After these two steps, things spiral out of control with “dehumanization”, which denies that the target group is even human.

Genocide Watch has outlined a guide to genocide, the so-called “eight stages of genocide”, which states that mass murder inevitably begins with the “classification” and “symbolization” of a target group. Classification refers to the split or separation of “us from them”, while symbolization represents the name calling once that split has occurred. After these two steps, things spiral out of control with “dehumanization”, which denies that the target group is even human.

In an interview with Foreign Policy magazine, Hatebase creator says that the real value of the database is in being able to spot real-world uses of hate speech.

“As soon as you have logged incidents of hate speech you can start mapping that stuff, looking at frequency, severity, the migration of terms geographically. There’s a whole lot of value when people start mapping it against the real world.”

Quinn points to a real-world example:

“If you were following events in Rwanda in the early 90s, you’d want to start looking for the word “cockroach” as a metric. That’s exactly the sort of thing we’re gunning for.”

One of Hatebase’s biggest challenges will be in trying to determine just which trends of hate speech are a precursor to possible violence. Unfortunately, as most of us have experienced, there’s a certain amount of ethnic hatred in every country. The difficulty lies in distinguishing this ‘background noise’ from more systematic and organized hatred that could ultimately lead to killing.

Sentinel Project Executive Director Christopher Tuckwood tells Wired.co.uk that they can get around this by using other sources of data to determine when and where hate speech trends are a concern.

“Hatebase gives us a reference point for what we should be listening for — picking that signal out of the noise — and then help with quantifying it. The real trick is to then connect those hate speech trends with other real-world phenomena.”

As an example of this, Tuckwood points to the recent reports of violence against the Baha’I minority in Iran, which correlates with an upsurge in reports of anti-Baha’I statements made by Iranian officials.

“Once we start to see early correlations between language and physical actions taken against a particular minority, we can do more accurate forecasting,” says Tuckwood.

The Nazi’s anti-Jewish propaganda was a sure sign of impending violence

Launched on March 25, Hatebase is still very much in its early stages. Very few incidents have been reported so far, but as the developers add further functionality in the coming months, they’re hopeful that it may one day become a valuable tool for NGOs and other groups trying to prevent violence.

Support our mission to keep content open and free by engaging with theCUBE community. Join theCUBE’s Alumni Trust Network, where technology leaders connect, share intelligence and create opportunities.

Founded by tech visionaries John Furrier and Dave Vellante, SiliconANGLE Media has built a dynamic ecosystem of industry-leading digital media brands that reach 15+ million elite tech professionals. Our new proprietary theCUBE AI Video Cloud is breaking ground in audience interaction, leveraging theCUBEai.com neural network to help technology companies make data-driven decisions and stay at the forefront of industry conversations.