BIG DATA

BIG DATA

BIG DATA

BIG DATA

BIG DATA

BIG DATA

You might have noticed the recent surge in “Data for Good” programs, where organizations devote some resources to doing something perceived to be good for people, or the environment or other causes that aren’t in the scope of their normal business strategy.

Some software vendors have picked this up and run annual award programs for customers that submit their qualifications to be noticed for these activities. I’ve been personally involved in quite a few of these and can say, categorically, a lot of it is nonsense. And that’s sad in a world that really needs the efforts of those who can most afford to be helpful.

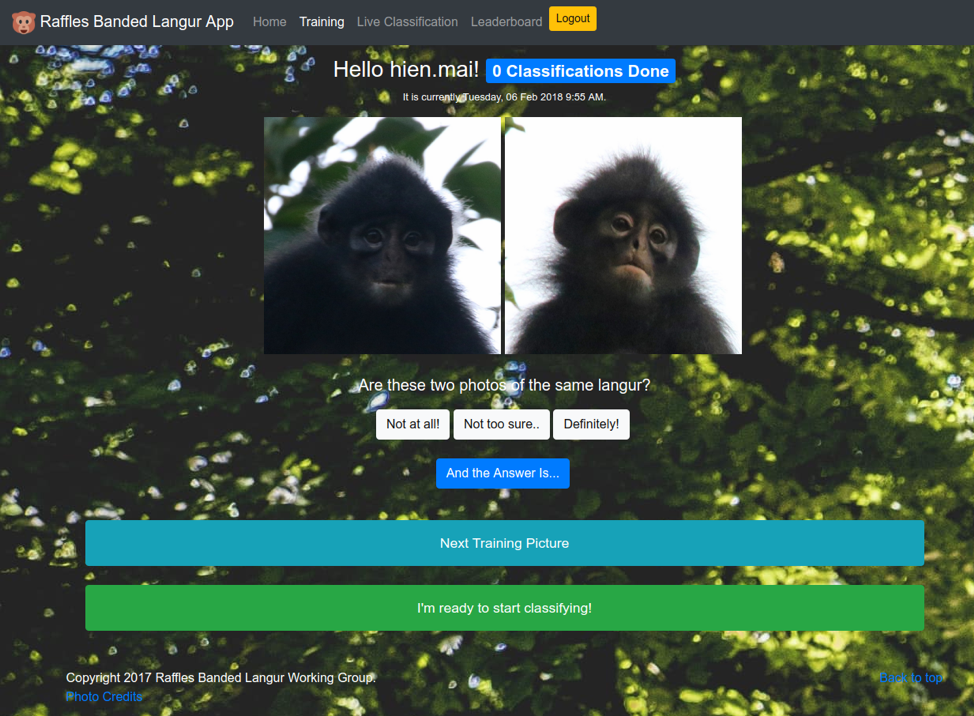

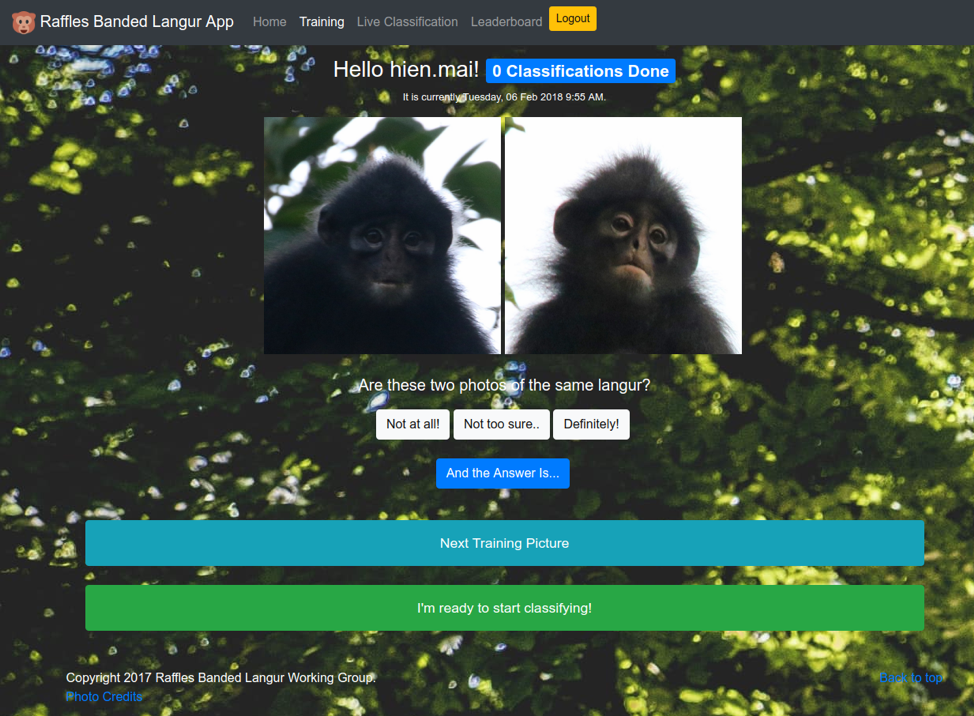

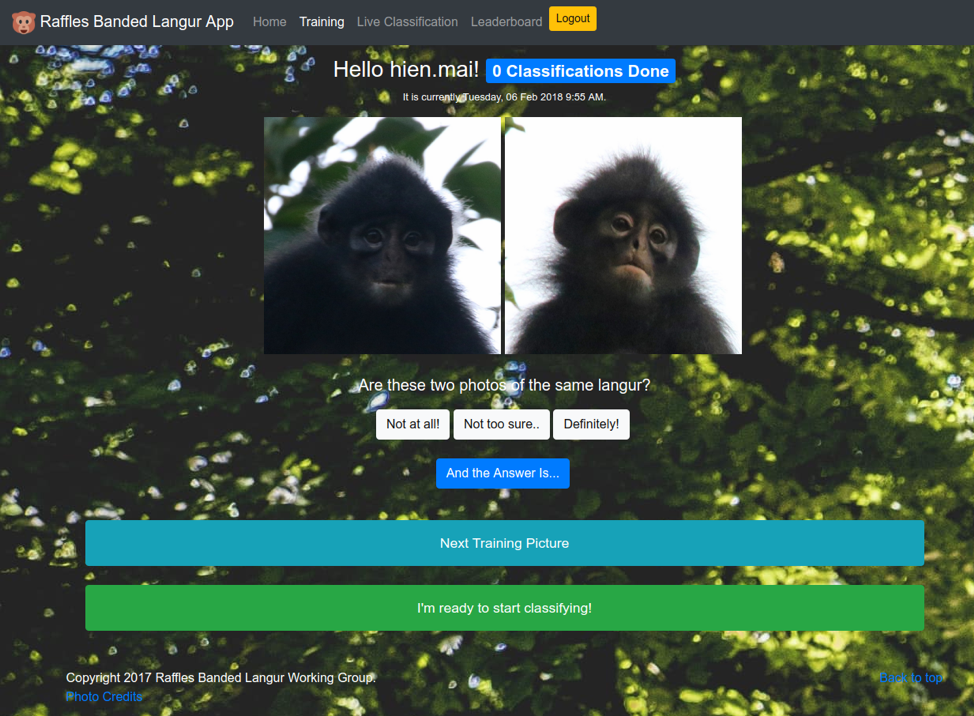

But there are some bright spots too. Take DataKind, for example, whose projects include leveraging data to protect Singapore’s endangered Banded Leaf Monkey (pictured) and using satellite imagery to generate awareness and funding for refugees.

According to the site, you can “join thousands of data do-gooders, mission-driven organizations and data lovers around the world eager to use data science in the service of humanity. If you’re an organization proposing a project, we’ll review your needs and let you know if we can help. If you’re signing up to volunteer, we’ll review your skills and keep in touch as projects come up that are a fit for your background.”

But a lot of the “for good” I see is pretty thin.

First, when I see a submission, I watch out for three things that cause me to cast a jaundiced eye to the application. The first and most obvious one is a thin, pro forma presentation that is clearly cut and pasted from some of its internal content. Stepping out of your normal business takes some commitment and resources and, most of all, has to show, in a verifiable way, that there has been some positive, planned-for impact. These submissions are usually full of “will happen,” or “can lead to,” and other vague predictions about the outcome, but nothing verifiable.

The second case is where an organization seems to want to get an award for doing what they are already supposed to do, such as hospitals, health insurers and government agencies. One that I judged recently was the Cleveland Clinic. Cleveland Clinic is, by its own definition, a nonprofit academic medical center, that provides clinical and hospital care and is a leader in research, education and health information. Its submission for an award was based on the proposition that it was using data to save lives.

Isn’t that what it’s supposed to do?

But there is a dark side to the Cleveland Clinic. It’s a tax-exempt organization that, like many hospitals, fought to preserve its not-for-profit status in the years leading up to the Affordable Care Act. As a result, it doesn’t have to pay tens of millions of dollars in taxes, but it is supposed to fulfill a loosely defined commitment to reinvest in its community. Since its founding, the community where Cleveland Clinic is situated has been deteriorating for decades.

That community is poor, unhealthy and — in the words of one national neighborhood-ranking website — “barely livable.” A third of the residents have diabetes. It’s the paradox at the heart of the Cleveland Clinic, as it lures wealthy patients and expands into cities such as London and Abu Dhabi. Its stated mission is to save lives, but it can’t save the lives in the neighborhood that continues to crumble around it, as it continues to condemn and raze parts of it to expand.

A third type of submission is an organization that is so truly not using data for good but, quite the opposite, twists the benefit of their mission to be “for good.” Monsanto made everything from Agent Orange to Roundup, for which it was recently given its first liability verdict of $289 million. Monsanto scientists have done more to conceal the deadly harm their products have wreaked on people than all the tobacco companies combined. But they did not submit an application for Roundup but for their biotech business “working with others to address the word’s food challenges.” There is a shorter name for genetically modified organisms or GMOs.

The bulk of Monsanto’s application described its very advanced, technologically speaking, application of what we call the “industrial internet of things.” Farmers buy seed from Monsanto with the promise of greater yields, but only if they scrupulously follow the protocols through the tilling and weeding, planting, growing and harvesting seasons. All the farm equipment is equipped with sensors that record whether the farmers are watering, weeding and the like at precisely the right amounts and times.

When the trucks that haul away the corn and soybeans, and the silos that store it, are massively instrumented and become a big-data analytics program at scale, one would have to give Monsanto high marks, except for two things: First, there is a strong possibility that GMO will not only not solve the world’s food supply; in fact, it may destroy it. And second, it aggressively lobbies against GMO labeling. I gave it a zero.

The good news about doing good is that there is a lot of it and it’s growing. One could argue that, just like a hospital, many nongovernmental organization shouldn’t be recognized for doing what they are supposed to.

But there is one that not only was the first to appear and have a major impact but is using modern data technology at the core of how it pursues its mission. Thorn: Digital Defenders of Children, previously known as DNA Foundation, is an international anti-human-trafficking organization that works to address the sexual exploitation of children. Despite the fact that Thorn was started by some very visible celebrities, Demi Moore and Ashton Kutcher, it is an effective tool in wide use, not just a celebrity feel-good front.

Thorn provides its product, Spotlight, free to law enforcement. It is an advanced cognitive-computing-based analytical tool to be used to organize and provide intelligence quickly within the chaotic online commercial sex market. It is smart enough to reveal information that is intentionally concealed and changing. Spotlight was built to support the investigative efforts of law enforcement to find child sex trafficking victims on the Internet.

I’ve seen other submissions that were a little more prosaic but still in my mind qualify as data for good. The City of Louisville used good data management and analysis to cut the time it took to get plows and salting on the road with a major storm, something that clearly has a positive impact on people in the city.

Kudos as well to IBM Research for the paper “An End-To-End Machine Learning Pipeline That Ensures Fairness Policies.” As machine learning drives more and more of daily experience, this issue of bias is reaching critical mass.

Bottom line: There are endless opportunities to use data for good, even some that can generate revenue.

THANK YOU