INFRA

INFRA

INFRA

INFRA

INFRA

INFRA

Much of the discussion around Intel Corp.’s current challenges understandably is focused on manufacturing issues and its ongoing market share skirmish with Advanced Micro Devices Inc.

But the core issue the chipmaking giant faces is it has lost the volume game, forever. When it comes to silicon, volume is king. As such, incoming Chief Executive Pat Gelsinger faces some difficult decisions.

On the one hand, he could take some logical steps to shore up the company’s execution, outsource a portion of its manufacturing and make incremental changes that would please Wall Street and probably drive shareholder value when combined with the usual stock buybacks and dividends.

On the other hand, Gelsinger could make much more dramatic moves, shedding its vertically integrated heritage and transforming Intel into a leading designer of chips for emerging multitrillion-dollar markets that are highly fragmented and generally referred to as “edge opportunities.”

We believe that Intel has no choice. It must create a deep partnership with a semiconductor manufacturer aspiring to manufacture on U.S. soil, and focus Intel’s resources on design.

In this Breaking Analysis, we’ll put forth our prognosis for Intel’s future and lay out what we think the company needs to do to, not only maintain relevance, but regain the position it once held as perhaps the most revered company in tech.

Let’s explore some of the fundamental factors we’ve been tracking that have shaped and are shaping Intel today, and our perspectives.

First, it’s important to point out that Gelsinger is walking into a really difficult situation — some might say chaotic — with lots of uncertainty.

Intel’s ascendency and manufacturing dominance was propelled by personal computer volumes and its corresponding development of an ecosystem the company created around the x86 instruction set. Why is volume is so critical in semiconductors? It’s because the player with the highest volumes has the lowest manufacturing costs. Although much has been written about achieving economies of scale with smaller fabs, the math around learning curves at volume is clear and compelling.

Most people are familiar with Moore’s Law, but much of the theory around volume economics can be explained better with Wright’s Law, named after Theodore Wright – T.P. Wright – a prominent aeronautical engineer who in the mid-1930s published a critical paper, “Factors affecting the costs of airplanes.” The law projects manufacturing costs as a function of cumulative production volumes.

Wright discovered that for every cumulative doubling of units manufactured, costs will fall by a constant percentage. The law articulates the benefits of moving up the experience curve (and consequently down the cost curve) and is highly applicable to semiconductor manufacturing. The law quantifies in manufacturing terms what Amazon Web Services Inc. CEO Andy Jassy often says about the evolution of cloud computing:

There’s no compression algorithm for experience.

In semiconductor wafer manufacturing, that cost decline from Wright’s Law is roughly 22% for a doubling of production. That means that when your cumulative production doubles, you get the benefits of lower costs from experience. When you consider the economics of manufacturing a next generation semiconductor technology – for example going from 10-nanometer to seven-nanometer technology — this becomes huge. The cost of setting up 7nm tech is much higher relative to 10nm, so the constant in Wright’s Law becomes critical.

Now if you can add to that the benefits of putting more circuits on a chip, your end costs of delivering processors can drop by 30-33%/year. The combination of learning curve effects and circuit density confers major advantages to the volume leaders. Consequently, if the time it takes to double volume is elongated, the learning curve benefits get pushed out, and you become less competitive from a cost standpoint. You can reach a stage where it will be impossible to implement new technology, because the volume is not sufficient to go down the learning curve quickly enough. That has happened in hard disk drives.

And that is what’s happening to Intel.

Intel famously missed mobile by passing on Apple Inc.’s iPhone opportunity. Intel, as did most, underestimated smartphone volume by 100 times. As a result, it handed its volume advantage to its competitors. Personal computer manufacturing volumes peaked in 2011 and that marked the beginning of the end of Intel’s dominance. One can’t help but recognize the irony that 25 years earlier, IBM Corp. had unwittingly handed its monopoly to Intel and Microsoft Corp.

Moreover, because Intel has a vertically integrated approach to design and manufacturing, its designers are limited by constraints in the manufacturing process. What used to be Intel’s ace in the hole, the best and lowest-cost manufacturing, has become a headwind. This no doubt frustrates Intel’s chip designers and cedes advantage to a number of competitors, including AMD, Arm Ltd. and Nvidia Corp., along with their volume manufacturing partners such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. and Samsung Ltd.

Other evidence of Intel’s decline from prominence can be seen when observing what some of the highest-profile innovators are doing in chip design, choosing to work with alternative suppliers and in many cases diversifying away from Intel. Apple, for instance, chose its own design based on Arm for the M1. Tesla is a fascinating case study to: It chose Arm-based components and its own design instead of chips from Mobileye (acquired by Intel). AWS, probably Intel’s largest customer, is developing its own chips, many using Arm components. And just last month it was reported that Microsoft, Intel’s duopoly partner in the PC era, was developing its own Arm-based chips for the Surface PCs and servers.

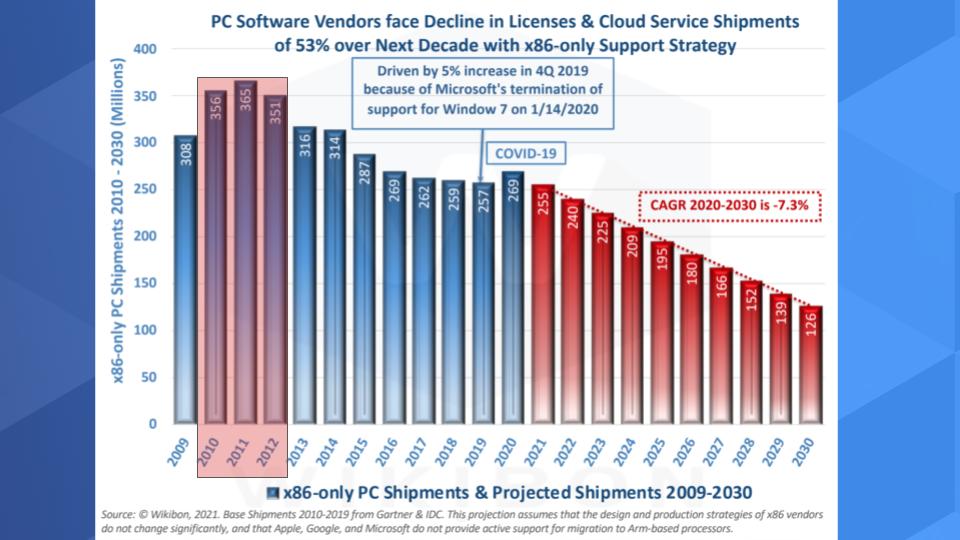

To stress the point, this chart above shows x86 PC volumes over time. The red highlighted area shows the peak years. PC volumes actually grew in 2020, in part thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic and the accompanying demand for laptops to support remote workers. But the rules of the volume game were already reset by mobile, and a decades-long victory march to the cadence of the Moore’s and Wright’s laws are gone.

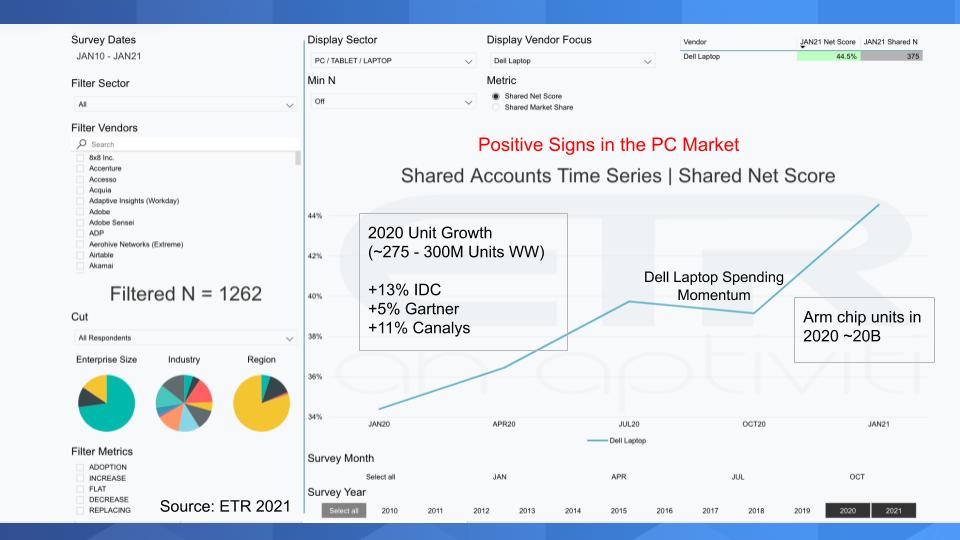

Below is a snapshot of Enterprise Technology Research’s data showing Dell’s laptop Net Score or spending momentum for 2020 into 2021. Dell’s client business has been very good and profitable for the company. Frankly it has been a pleasant surprise. PCs are doing well, as you can see by the unit growth on the insert. Approximately 275 million maybe as high as 300 million PC units shipped worldwide in 2020, up double digits by some estimates.

But in the all-important volume semiconductor manufacturing game, PCs are no longer the king. Collectively, Arm chip units surpassed 20 billion worldwide last year. Comparing Arm chips shipped with x86 PCs is not apples-to-apples, but the numbers speak for themselves:

The wafer volume for Arm chips dwarfs that of x86 by a factor of 10 times.

Back to Wright’s Law. How long will it take Intel to double wafer volumes? Gelsinger understands this dynamic probably better than anyone in the world – certainly better than we do.

Moreover, if you look at the performance and price-performance of Arm compared with x86, the picture continues to favor Arm, quite dramatically. Arm design to production cycles are faster, the technology is climbing the learning curve faster and riding the cost curves down at a more accelerated rate.

As you look out to the future, the story for Intel’s PC dominance also does not look promising.

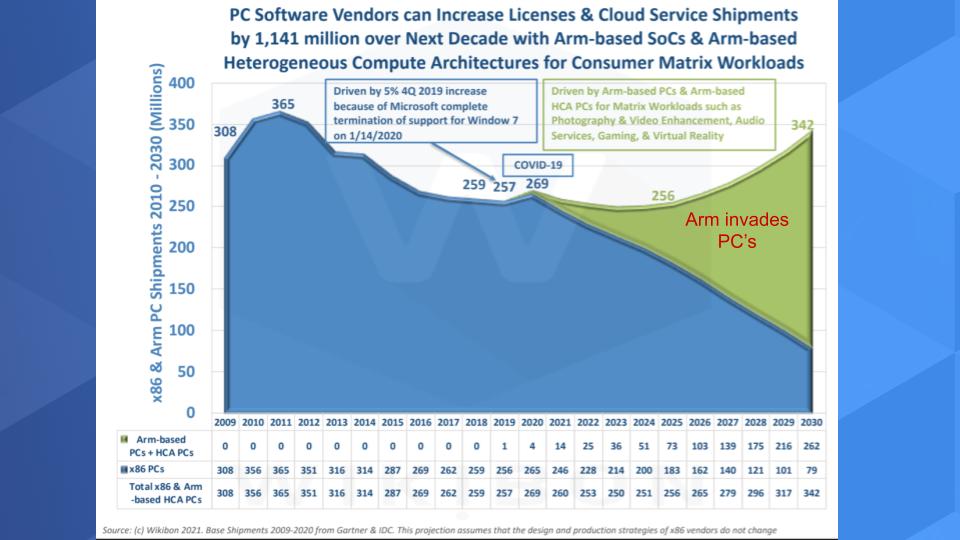

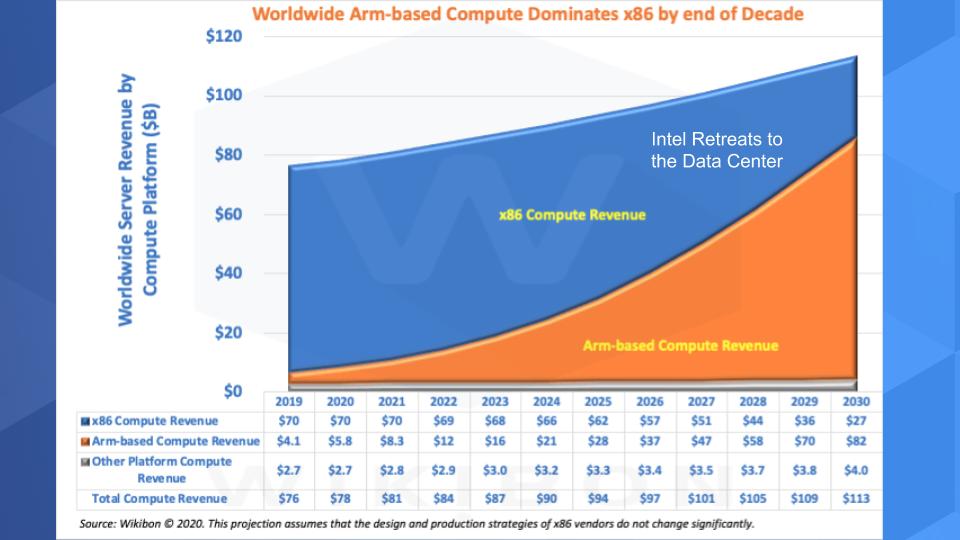

The chart above shows Wikibon’s 2020 forecast for Arm-based compared with x86-based PCs. It also includes some other devices, but you can see what happens by the end of the decade. As we’ve seen with the M1 at Apple, Arm is slowly eating away at PCs and much better-positioned for these emerging devices that support things such as video and virtual reality systems.

So again, the volume game is over for Intel and with it, the company’s manufacturing cost advantages. It will never win it back.

Yes, and that business generates much higher revenue per unit. But even so, we still see revenue from Arm-based systems surpassing that of x86 by the end of the decade, as shown in the chart below. Arm compute revenue is shown in the orange area, with x86 in the blue.

That means to us that Intel’s last moat will be its position in the data center. It has to defend that at all costs.

But that’s a near-term play. We don’t think Pat Gelsinger is a defensive-minded general. On the contrary, he’s a masterful strategist who thrives on forward momentum. More on that later….

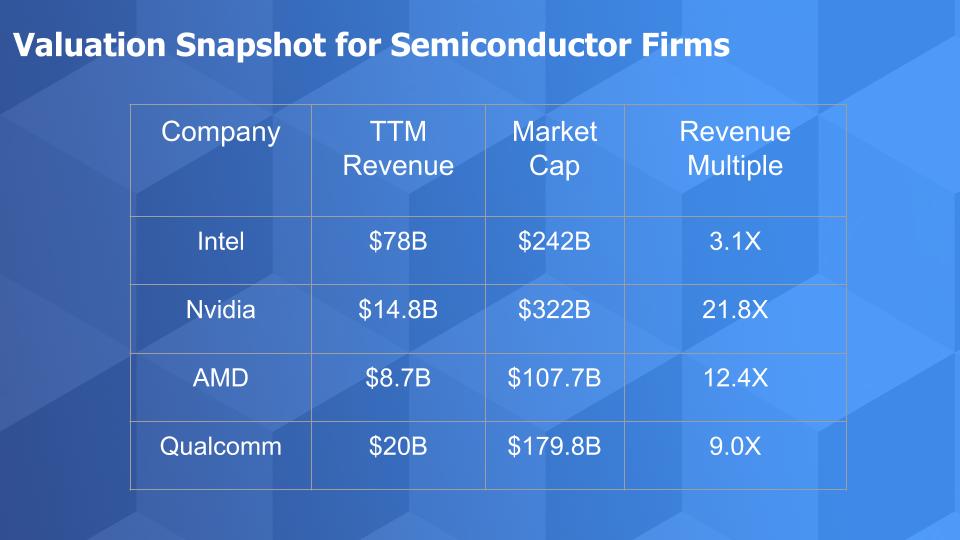

Financial markets know there’s something wrong, and you can see it reflected in the valuations of semiconductor companies.

The chart above compares the trailing-12-month revenue and market valuations for Intel, Nvidia, AMD and Qualcomm Inc. And you can see at a TTM revenue multiple of three times, compared with about 22 times for Nvidia and about 10 times for AMD and Qualcomm. Intel is lagging behind.

The graph below shows Intel’s performance for the past 12 months compared with the Nasdaq and you can see the major divergence. The stock reacted very well to the appointment of Gelsinger, which is no surprise. It’s hard not to be sanguine about Pat’s decision to return to Intel.

The questions people are asking are: What’s next for Intel? How will Pat turn the company’s fortunes around? How long will it take? What moves can he and should he make? How will they be received by the market and internally within Intel’s culture? Will things get worse before they get better?

These are serious questions! And people are split on what should be done. We’ve heard everything from “Pat should just clean up the execution issues and not make any major strategic moves” to “Intel should do a hybrid outsourced model to aggressively move out of manufacturing.”

Here are some recent headlines and comments within that sum up the sentiment:

Intel Will Likely Turn to Taiwan Semiconductor for Chips. Here’s Who Benefits Most (Barrons).

Microsoft Designing Own Chips for Servers, Surface PCs (Bloomberg).

Intel Has Fallen Behind Rivals and the Rest of Tech. Why Its Stock Can Rise Again (Barrons).

Intel is Replacing CEO Bob Swan. Investors are Cheering the Move (Barrons).

Following are a sampling of the comments from the articles and quotes from various analysts:

Intel has indicated a willingness to try new things, and investors expect the company to announce a hybrid manufacturing approach in January. Quoting CEO Swan, “What has changed is that we have much more flexibility in our designs, and with that type of design we have the ability to move things in, and move things out…and that gives us a little more flexibility about what we will make, and what we might take from outside.”

Let’s unpack that a bit. Intel has a highly integrated workflow from design to manufacturing and production. But to us, the designers are artists and they would be helped by the flexibility one would think would come from outsourcing manufacturing to give designers more options to take advantage of 7nm or 5nm process technologies, versus having to wait for Intel manufacturing and live by its constraints. It used to be that Intel’s process was the industry’s best and it could supercharge a design or even mask certain design challenges to maintain its edge. But that’s no longer the case.

Here’s the sentiment from an analyst from Citibank analyst Daniel Danely:

Danely is confident that Intel’s decision to outsource more of its production won’t result in the company divesting its entire manufacturing segment. He cited three reasons: 1) It would take roughly three years to bring a chip to market; 2) Intel would have to share IP; and 3) It would hurt Intel’s profit margins. He said it would negatively impact gross margins by 10 points and would cause a 25% decline in EPS.

To this we would say: 1) Intel needs to reduce its current cycle time to go from design to production from three to four years down to under two years; 2) What good is intellectual property if it’s not helping you win in the market? and 3) Profitability is nuanced, as the UBS analyst Timothy Arcuri explains:

“We see no option but for Intel to aggressively pursue an outsourcing strategy…” He wrote that Intel could be 80% outsourced by 2026. Just going to 50% outsourcing he said would save the company $4B annually in CAPEX adding 25% to free cash flow.

So maybe Gelsinger has to sacrifice gross margin and earnings per share for the time being, reduce cost of goods sold by outsourcing manufacturing, lower his capital expenditures and fund innovation in design with free cash flow.

We completely agree that in the near- to mid-term, Intel’s fortunes won’t be magically reversed, but we believe Gelsinger needs to look in the mirror and ask:

What would Andy Grove do?

Grove’s motto, “Only the paranoid survive,” is famous. Less well-known are the words that preceded that quote:

Success breeds complacency. Complacency breeds failure.

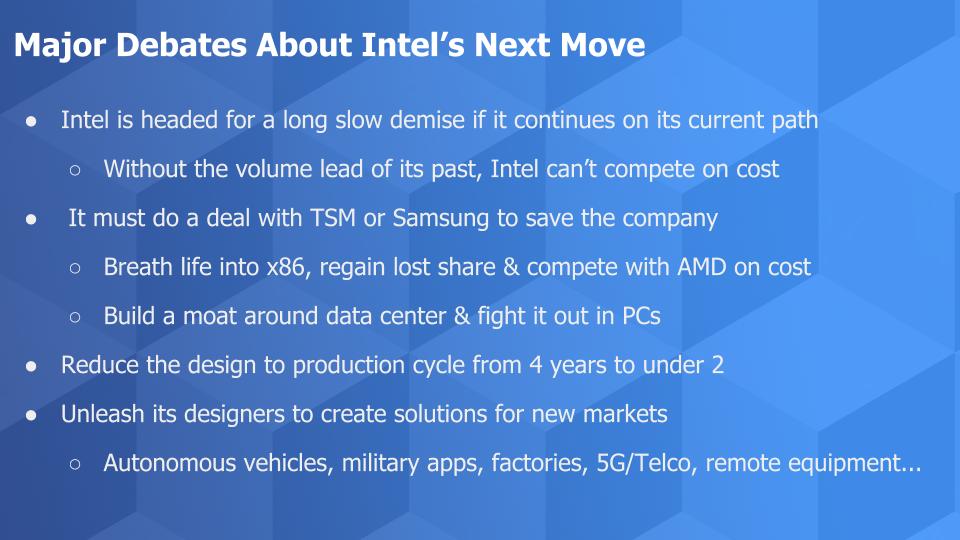

Intel in our view is headed on a path to a long, drawn-out failure if it doesn’t act. It simply can’t compete on cost as an integrated manufacturer because it doesn’t have the volume. Period.

So what will Pat Gelsinger do? We’ve done close to 30 interviews on theCUBE with him. And we just don’t think he’s taking this job to make some incremental changes to Intel to steady the ship and get the stock price back up. Why would that excite Pat Gelsinger? That’s definitely not what Andy Grove would want. And Gelsinger’s certainly not in it for the money.

No, Gelsinger is a visionary with a deep understanding of tech, architectures, trends, markets, people and society. He’s a dot connector. And he loves Intel– he’s a legend at the company where he spent 30 years.

Here’s what we strongly believe. We think Intel must do a deal with TSMC or Samsung – perhaps a joint venture or some type of innovative structure that both protects its IP and secures its future. Both of these manufacturers would love to have a stronger presence in U.S. markets where Intel has many manufacturing facilities. They may even be willing to take a loss to partner more deeply with Intel.

In our view, Intel needs to get to 5nm within two years to remain cost-competitive and defend its base.

It can’t do this in our opinion without a strategic manufacturing partnership. If it tries to go it alone, the costs of introducing next-generation technologies will be so expensive it will bankrupt the company. How’s that for paranoia?

To be clear, we believe that core Intel should get out of the business of manufacturing semiconductors. Set up a JV and spin the venture off so you can profit but focus the core company on design.

That will allow Intel to compete better on a cost basis with AMD, defend its data center revenue — and fight the good fight in PCs, better preparing for the coming onslaught from Arm.

Intel should put a laser focus on reducing its cycle times and unleashing its designers to create new solutions. Let a manufacturing partner who has the learning-curve advantages enable Intel designers to innovate and extend ecosystems into new markets. Autonomous vehicles, factory floor use cases, military, security, distributed cloud, the coming telco explosion with 5G, AI inferencing at the edge. Just think about the opportunities for Intel in 5G, which the company has pegged as an $18 trillion opportunity.

Bite the bullet and give up on yesterday’s playbook and reinvent Intel for the next 50 years. That’s what we’d like to see and that’s what we think Gelsinger will conclude when he channels his mentor.

We sincerely wish the best for Pat, the people at Intel and the continued success of a great American company.

Many thanks to David Floyer for his contributions to this post and his excellent research on this topic over the past seven years.

What do you think? Please comment on our LinkedIn posts. Other ways to get in touch: Email david.vellante@siliconangle.com and DM @dvellante on Twitter. Remember these episodes are all available as podcasts wherever you listen. And don’t forget to check out ETR for all the survey data.

Here’s the full video analysis:

Support our mission to keep content open and free by engaging with theCUBE community. Join theCUBE’s Alumni Trust Network, where technology leaders connect, share intelligence and create opportunities.

Founded by tech visionaries John Furrier and Dave Vellante, SiliconANGLE Media has built a dynamic ecosystem of industry-leading digital media brands that reach 15+ million elite tech professionals. Our new proprietary theCUBE AI Video Cloud is breaking ground in audience interaction, leveraging theCUBEai.com neural network to help technology companies make data-driven decisions and stay at the forefront of industry conversations.