BIG DATA

BIG DATA

BIG DATA

BIG DATA

BIG DATA

BIG DATA

More than eight years into the modern era of artificial intelligence, the industry has moved past the awe of generative AI 1.0.

The novelty is gone and in its place is scrutiny. Enterprises are less impressed by demos and more impatient about outcomes. Market watchers are increasingly skeptical about vague narratives, and the commentary has shifted from “Look what AI can do” to “Show me the money, give me visibility and control.”

This dynamic is backstopped by our central premise that the linchpin of AI is data; and specifically data in context. The modern data stack of the 2010s – cloud-centric, separation of compute and storage, pipelines, dashboards and so on — now feels trivial. The target has moved to enabling agentic systems that can act, coordinate and learn across enterprises with a mess of structured and unstructured data, complex workflows, conflicting policies, multiple identities and the nuanced semantics that live inside business processes.

The industry remains excited and at the same time conflicted. To tap an oft-cited baseball analogy: The first inning was academic discovery in and around 2017 – papers explaining transformers and diffusion models. But most people weren’t paying attention. The second inning was the ChatGPT moment and the AI heard ‘round the world, which has brought excitement and plenty of hype.

Welcome to the third inning of the modern AI era. In this special Breaking Analysis, we assess the shift from the shock of “What is this gen AI thing?” to “How do we make it work for us?” And how can we get agents to reliably take action to deliver the productivity gains the tech industry has promised?

To do so, we’re pleased to host our fifth annual data predictions power panel with collaborators from the Cube Collective, members of the Data Gang, and some of the industry’s leading data analysts. With us today are five industry experts focused on data and related topics: Sanjeev Mohan of Sanjmo, Tony Baer of DB Insight, Dave Menninger of ISG Software Research, Kevin Petrie of BARC, and Andrew Brust of Blue Badge Insights.

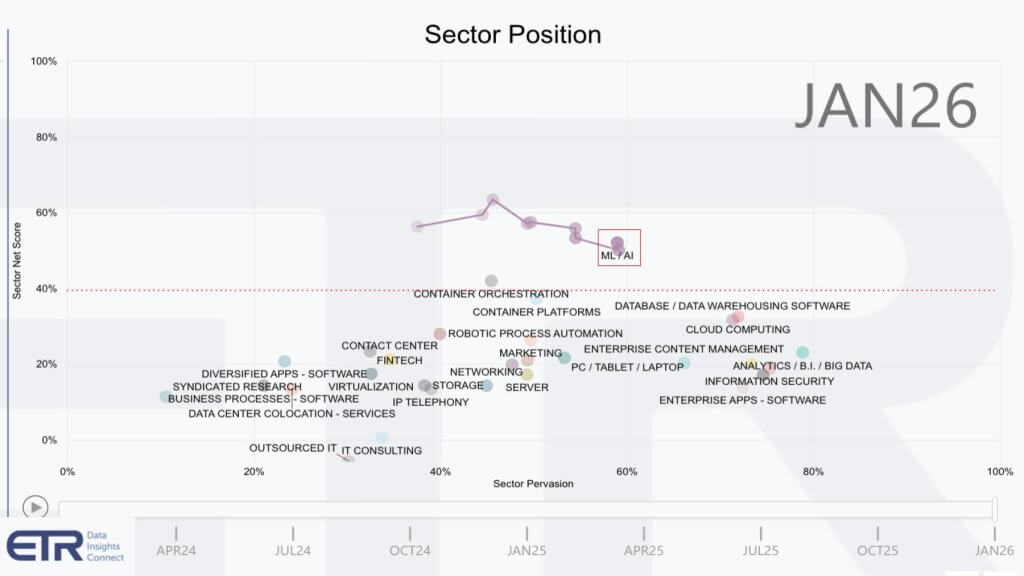

Now as is our tradition, before we get into it, we want to share some survey data from our friends at Enterprise Technology Research to underscore how much the industry has changed. ETR performs quarterly spending intentions surveys of more than 1,700 information technology decision-makers. And I want to isolate just on the machine learning/AI space to show you how things have changed.

This graphic shows spending by sector. The vertical axis is Net Score or spending momentum within a sector and the horizontal axis is Pervasion in the data set for each sector based on account penetration. Here we go back to April 2024. That red line at 40% indicates highly elevated spending velocity and if you didn’t know it already – ML/AI stands above all sectors, despite a recent modest deceleration in spending momentum.

Perhaps the tapering in momentum is an indication that we still need better AI. A Workday survey this week showed that 85% of respondents said AI saved one to seven hours a week, but more than a third of the time savings is lost to correcting errors, rewriting and verifying content, and just 14% reported consistently positive outcomes from AI.

Nonetheless, the ETR data is showing steady progress over the last six months.

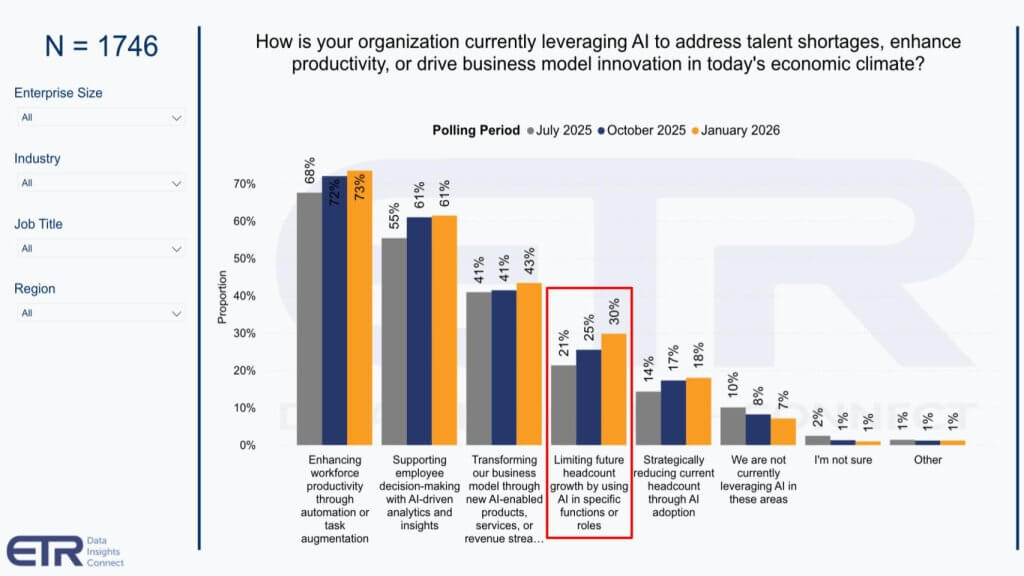

When asked how they’re leveraging AI, more than 1,700 customers continue to cite productivity, decision support and business transformation as the leading benefits, with gradual increases in citations. But look at the meaningful uptick since last July in future headcount avoidance. Moving from 21% of the sample in midsummer to 30% today.

Finally let’s look at some of the players in the mix – a few of them we’ll talk about today.

Same dimensions with spending velocity on the Y axis and account penetration on the X; but some notable changes. We’ve inserted a chart in the lower right corner so you can see how the dots are plotted – Net Score and Ns in the survey – remember anything above that red dotted line indicates highly elevated momentum.

The point is the industry continues to shift before our eyes and customers must squint through the noise and place bets amidst all the chaos.

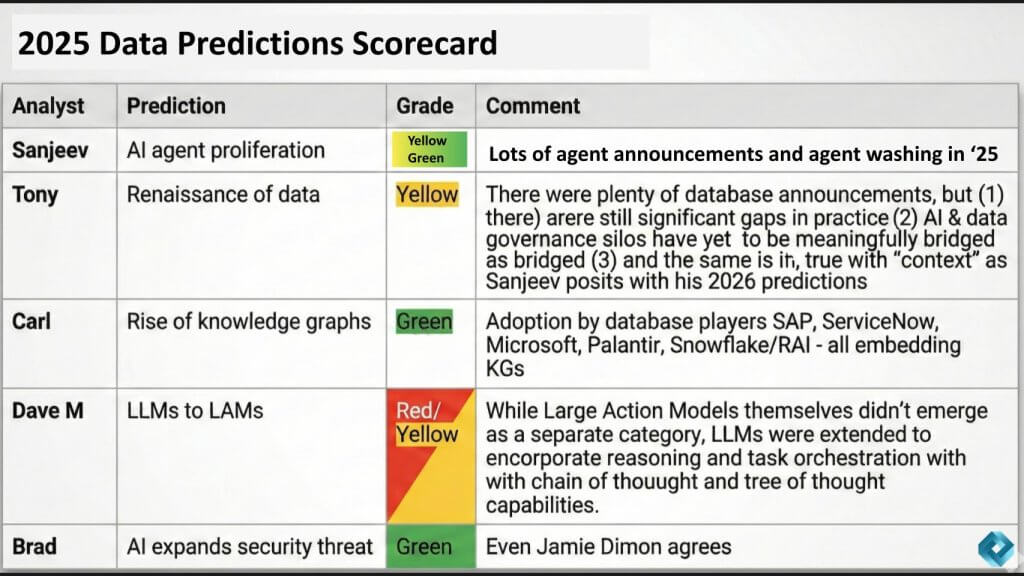

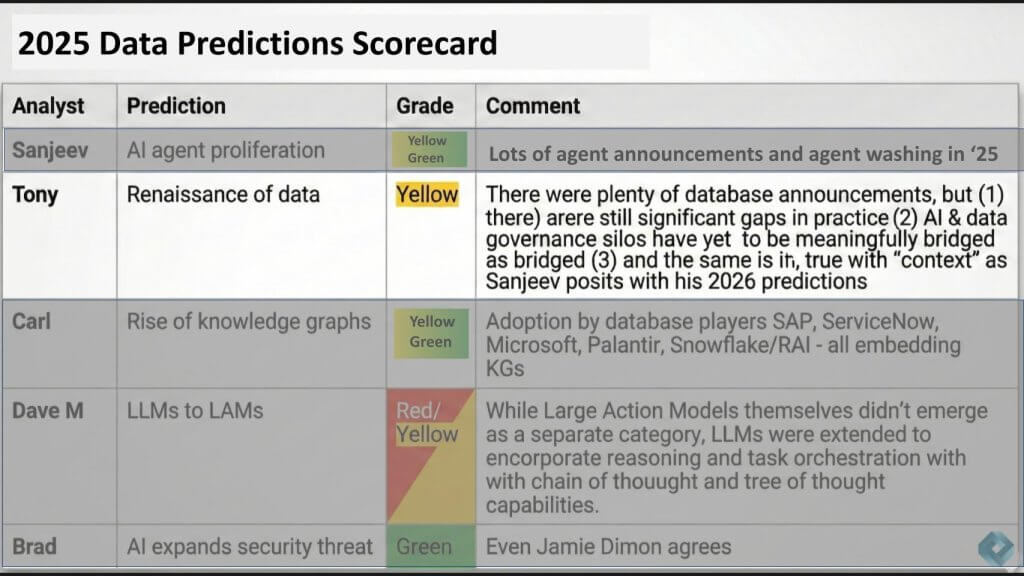

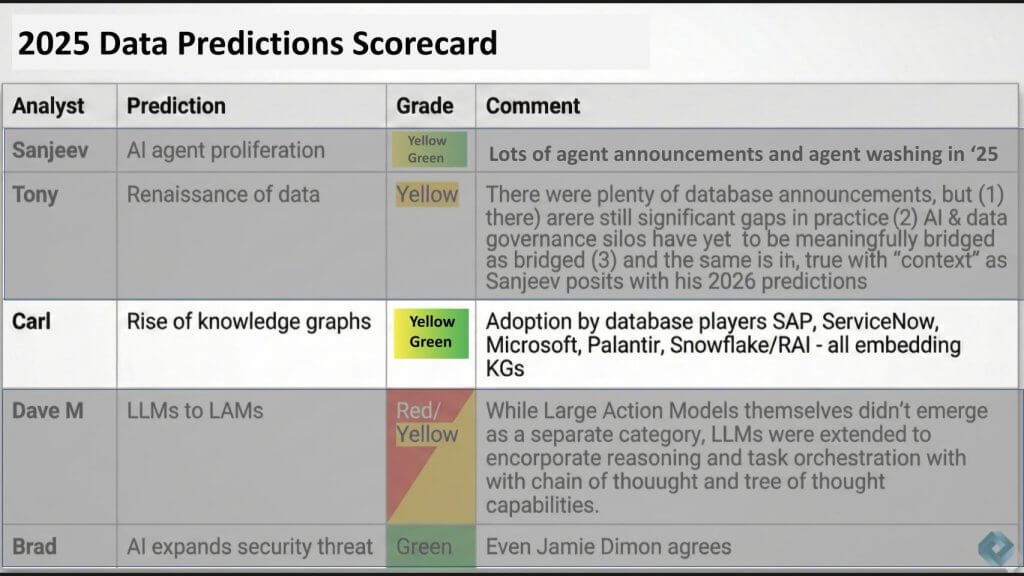

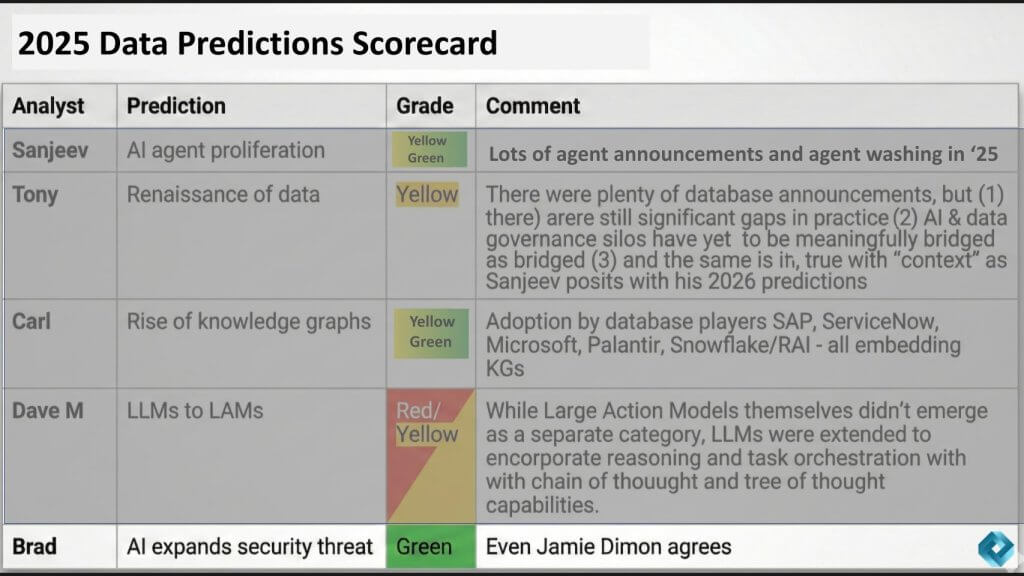

OK, with that as background, let’s get into the 2025 prediction review. The graphic below shows all of the 2025 Data Gang predictions for each analyst in one table.

It shows the prediction and a self-analyst rating on whether the prediction was a direct hit, which is green, a glancing blow, which is yellow, or a miss, which is the red. So a quick scan of the heat map shows you the data gang had a mixed performance in its 2025 predictions. Each of our analysts will now review and you can decide on the rating.

Watch Sanjeev’s look back on his 2025 predictions.

Sanjeev Mohan opened the 2025 prediction review by revisiting his forecast that AI agents would rise and proliferate. In his view, the call was mixed, largely because what counts as an “agent” has become highly elastic depending on who is answering the question.

Mohan’s core point was that the market has clearly moved in the direction he anticipated – agents are everywhere – but that breadth has come with semantic drift and rebranding. He observed that “everybody rebranded” and that “everyone now has an agent doing all kinds of things,” creating the impression of over-proliferation. In other words, the label has spread faster than the substance, and that made it difficult to give himself a “clean green” rating.

At the same time, he argued, there are tangible wins in narrow domains. Mohan pointed to single-task agents, with coding as the most visible example. He cited a claim attributed to Anthropic’s chief technology officer that “100% of Claude’s new additions have been done by Claude Code,” calling that “phenomenal.” He also referenced early traction in customer service and a few other areas, reinforcing that focused agents are beginning to deliver meaningful outcomes.

Where he drew a firm line was on the more ambitious goal that agents would be embedded inside complex workflows, operating autonomously and making decisions end-to-end. On that definition, Mohan’s assessment was that the story is not complete and “we are not there yet.” The market has proven it can ship useful point solutions; it has not yet demonstrated broad, reliable autonomy inside multistep, decision-rich enterprise workflows.

Mohan also revisited a second component of his prior outlook that by this year’s panel, everyone would have personal agents. He maintained that directionally he still believes it will happen, but he tempered the timing, saying the technology remains too difficult to mainstream, and that this milestone will likely have to wait another year.

Watch Tony Baer review and rate his 2025 prediction.

Tony Baer revisited his 2025 call that the industry would see a renaissance of data, driven by the following simple premise: If AI is the spotlight, then good data becomes the fuel, and both vendors and customers would be forced to redirect attention accordingly. Baer graded himself yellow, not because the direction was wrong, but because the outcome was uneven depending on whether one looks at vendor activity or customer execution.

On the vendor side, Baer argued the year delivered unmistakable signals that data moved “front and center.” The most prominent indicator, in his view, was the rapid coalescing around Model Context Protocol. He underscored how unusual the velocity was: a framework announced “very late in 2024” becoming, within roughly a year, a de facto industry standard, and then moving into open-source stewardship “under the Linux Foundation.” For Baer, the speed of MCP’s adoption demonstrated that the industry broadly recognizes the importance of standardized connections to data.

He then pointed to what he described as a strong year for Postgres, citing “three new” Postgres platform entries and highlighting what he called “Snowbricks” – his shorthand for Snowflake and Databricks – each buying a Postgres platform to complement their analytics stacks. Baer suggested one prime use case could be a state repository or state store for agents – a place to persist agent state. He said Microsoft makes a similar argument with HorizonDB, reinforcing the theme that operational data substrates are being repositioned as foundational components for agent-driven systems.

Beyond Postgres and MCP, Baer cited several other indicators that the “data renaissance” was real in product terms:

When pressed on why, given all that, he still chose yellow, Baer said “the world is not just vendor announcements.” His expectation included customers “rising to the occasion,” and on that front he saw meaningful gaps. He emphasized that data governance and AI governance remain largely siloed, and that too many organizations are still running “the same old practices.” He also called out knowledge graphs as an area where he expected to see more progress; instead, he has seen “a lot of talk,” but not the level of adoption he anticipated.

Baer anchored this caution with a specific data point from an AWS-released study in that 40% of chief data officers still cite perennial problems with data quality and data integration. In his observation, the persistence of these “same little battles” is precisely why he resisted “declaring victory and going home.” The headline for Baer’s scorecard was not that the renaissance thesis failed – rather, that the industry’s tooling and vendor narratives advanced faster than customer governance and adoption patterns.

Watch the panel review Carl Olofson’s 2025 prediction on knowledge graphs.

The panel returned to the topic of knowledge graphs in the context of a 2025 prediction made by Carl Olofson, who was not present because he’s retired. Carl predicted the rise of knowledge graphs, and this author said he had initially graded that call green as a “knowledge graph fanboy.” However, that optimistic grading ran into a reality check from the discussion on the panel, including skepticism voiced earlier that suggested enterprise adoption may not be accelerating.

To ground the debate, Kevin Petrie provided additional context. Petrie cited a forthcoming BARC Research analysis from his colleagues. He summarized the key finding as follows: Among AI adopters, 27% had knowledge graphs in production in late 2025, compared with 26% in early 2024 – barely an uptick over roughly a year and a half. Petrie added that what declined was earlier-stage activity – evaluations and proof-of-concepts went down, suggesting that the pipeline for knowledge graph implementations has slowed.

Petrie indicated that slowdown as surprising given his belief that knowledge graphs “have a lot of value to offer.” But he also pointed to what he sees as a primary gating factor in complexity – specifically “the assembly and the preparation of inputs” needed to build and operationalize knowledge graphs. In his view, that implementation headwind is materially constraining momentum, even as the conceptual value proposition remains strong.

After hearing Petrie’s data and rationale, we revised Carl’s score in real time, moving Olson’s prediction from green to a more qualified yellow-green.

Watch Dave Menninger’s review of his 2025 prediction.

Dave Menninger revisited his 2025 prediction on the shift from LLMs to “LAMs” (large action models). In reviewing it, he positioned the call as an extension of the same theme raised earlier in the discussion – the gap between single-task wins and complex agents that can coordinate actions across multistep workflows.

Menninger’s starting point was his prior assessment of what was missing in LLMs. In his view, LLMs were – and largely still are – strong at generating text, but not inherently strong at planning and executing a series of tasks. That deficiency is relevant because the agentic future depends on coordinated action, not just fluent output. On that basis, he predicted a new class of models would emerge specifically to address execution and planning, which he labeled large action models.

On the grading, Menninger was harsh to himself, saying the “LAMs went to slaughter.” That was the red portion of his scorecard – his specific forecast that a distinct category of “LAM” models would emerge – and did not play out the way he expected.

However, he argued the underlying premise proved out, which is why he gave himself yellow alongside red. The market did, in his estimate, have to confront the planning/execution gap, and it was addressed – just not through a separate model category. Instead, the path forward was that mainstream models were extended with the capabilities required to support agentic behavior. Menninger characterized those extensions as including:

Menninger’s conclusion was that the issue was real, but the industry arrived at a different solution than the one he predicted. That mismatch between correct problem framing and incorrect solution form-factor is what, in his view, earned the prediction a red and a yellow rather than a clean pass/fail.

Watch the team rate Brad’s 2025 prediction on security.

We wrapped the 2025 look back with a final reference point from Brad Shimmin, recalling that he “threw a bunch of cold water” on the prior year’s session by arguing that security would be the blocker to AI. The panel unanimously agreed that security is not a side issue and become a key gravitational force shaping what is possible in AI as in most enterprise markets.

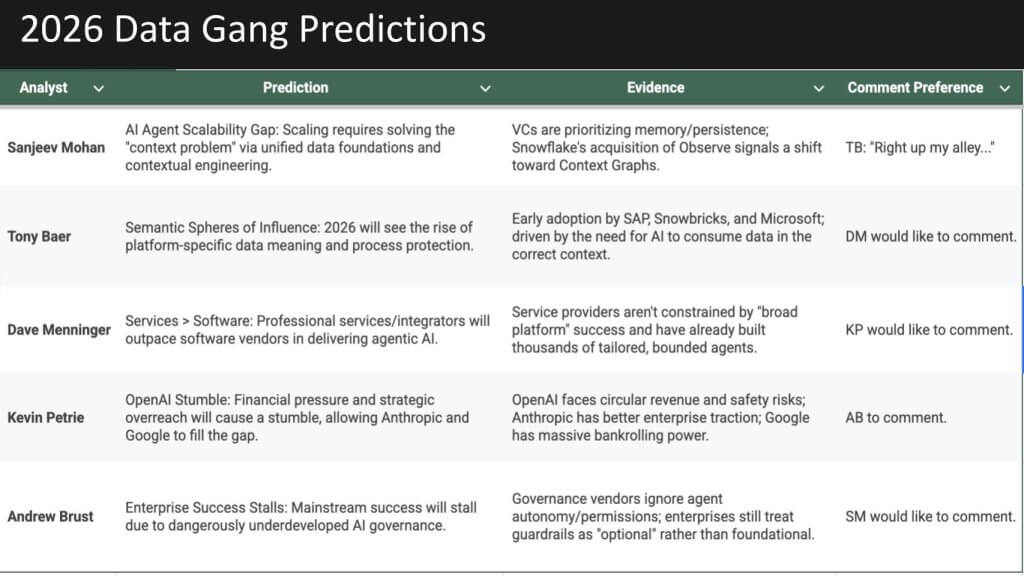

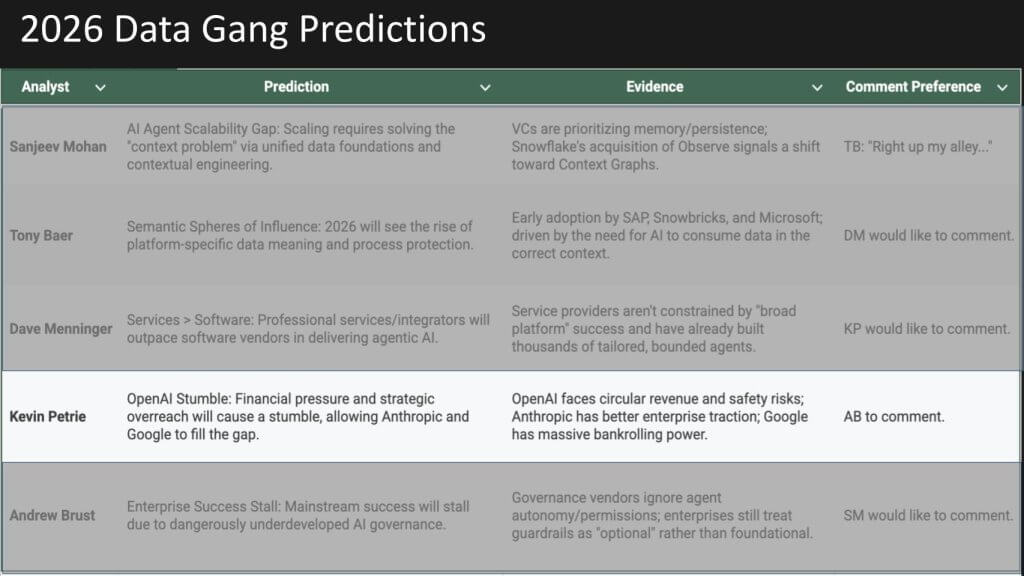

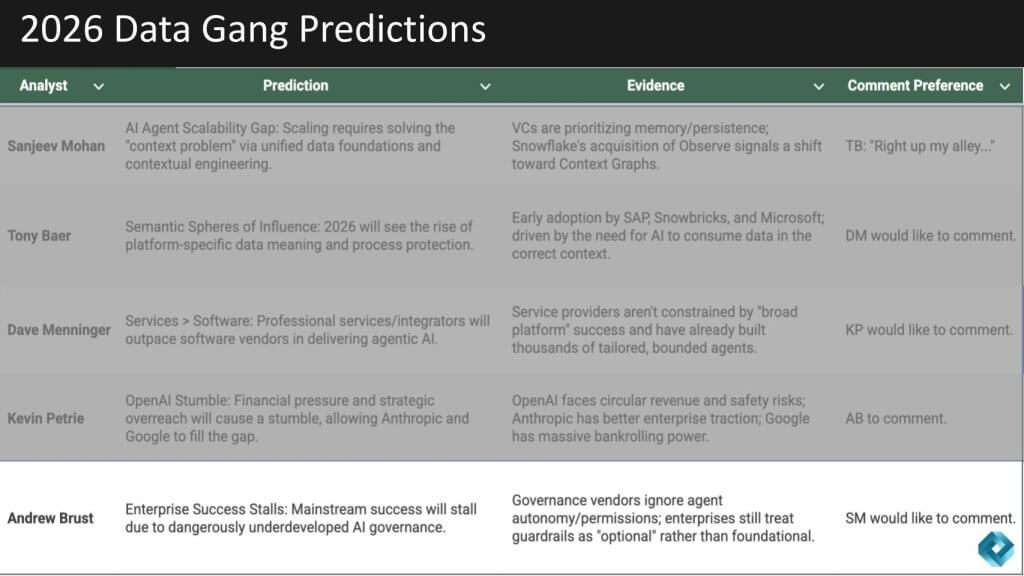

With the review of 2025 complete, we now pivot the discussion to the core of the episode – the 2026 predictions. The format is a designated analyst presents each prediction, followed by comments from one or two other analysts. As shown below, the 2026 predictions are all data-related or at least adjacent, spanning context, semantic layers and services as software, alongside skepticism on OpenAI and governance as a blocker. With that setup, let’s dive in.

Watch the discussion around Sanjeev Mohan’s prediction.

Sanjeev Mohan framed his 2026 outlook as the product of a midcourse correction. His initial instinct was to forecast a continuation of the “unification” narrative – more consolidation and M&A – citing examples such as Snowflake buying Observe and arguing the story is no longer just “data as infrastructure.” But early in the year, he saw a different thread take over. Inspiration came from a paper circulated on LinkedIn titled “The next trillion- dollar opportunity is context graphs,” and suddenly the platform “blew up” with daily posts about context graphs. That shift in the discourse drove what he called a “bipolar” prediction.

On the first pole, Mohan said “absolutely 100%” that large language models – and what he also referenced as large action models – will require context to do their job and be successful. On the other pole, he predicted the industry will squander the year and 2026 will be spent arguing and debating about context graphs, and “we will not have it.” In his view, the pattern will look familiar with a big concept, clear bottleneck and weak implementation reality. He compared it to data mesh – an attractive idea that triggered extensive debate but lacked durable, repeatable adoption patterns.

Mohan’s critique centered on the absence of basic foundations where there is no accepted standard, no consistent implementation model, and no stable definition. He asked pointed questions that were meant to expose the gap between rhetoric and engineering: For example: How do I know I have a “chief context graph”? Is there a standard? Is there a way to store stuff? He argued the industry cannot agree on a definition, and that even today the term context graph is being defined broadly, which sets the stage for maximal vendor and community noise without commensurate progress.

To make the concept concrete, Mohan drew a distinction between knowledge graphs and the kind of context he believes LLMs would benefit from. A knowledge graph, he argued, can help traverse traditional transactional data – who bought what and when – but it typically misses the “why.” That why lives outside the transaction system in web searches, logs, emails and support interactions. In his framing, context emerges when those signals are related back to traditional enterprise data, producing a richer picture. His prediction, however, was not that this will be broadly solved in 2026; it was that every company will claim to have a context graph, but the industry “won’t be successful.”

Tony Baer agreed with Mohan’s diagnosis and added to the critique with metaphor. He argued that “context is very slippery” and hard to define operationally. Something you recognize “when you see it,” but struggle to specify crisply in advance. Baer said Mohan’s prediction mirrors the same struggle the industry has had with knowledge graphs – trying to get arms around what knowledge is and how to structure it.

Baer introduced a modest note of optimism from his podcast partner Sudhir Hasbe (Neo4j, former Google). The thrust of that exchange, as Baer put it, was that AI can help guide the assembly process. He analogized it to how language models can inspect databases and produce ideas about schema, indexing, and related operational decisions. In Baer’s view, there may be a role for AI to assist in building and organizing context, but he “fully” agreed with Mohan that the industry will spend the year struggling to define what context is.

Additional panel comments reinforced the gap between concept and execution. The group’s sentiment was lots of discussion, little implementation, aligning with Sanjeev’s premise.

The discussion then widened into a concrete example of the spectrum of views inside the research community, with one camp arguing enterprises must do the hard work of building a knowledge graph or “4D map” of the enterprise – people, places, things and processes – akin to a digital representation of an enterprise, citing approaches associated with Palantir and referencing Celonis. The other end of the spectrum argues the problem is too complex to solve manually at scale and that AI will need to do more of the heavy lifting – echoing Baer’s suggestion that AI can help guide the outcome.

Watch the discussion around Tony Baer’s prediction.

Tony Baer positioned his 2026 prediction as a pragmatic counter to the context-graph debate. In his view, semantics are more doable than context, largely because semantics are a “known quantity” with decades of precedent. He reached back to the BusinessObjects Universe era to make the point that the semantics tier functioned like a metrics store, designed to prevent teams from “reinventing the wheel” every time they did reporting.

Baer’s argument was not that semantics solves context end-to-end. Rather, he said, semantics “goes a good bit of the way” but “doesn’t do the whole job” of establishing context. The practical insight he emphasized is that last year’s focus on “good data” proved insufficient – what matters is the right data, and that inevitably reintroduces the need for explicit meaning and relevance. He contrasted business intelligence-era semantic layers with modern AI requirements. BI operated inside a walled garden (warehouse/mart), where relevance was implicit because the data was curated for the questions being asked. With AI, the boundary goes away – systems reach beyond the walled garden – so context must be explicit, and Baer described semantics as a step toward putting the capability into operation.

From there, Baer forecast a renewed focus on semantic layers and metric stores, and he tied that to how major enterprise application vendors will extend their influence in an AI era where they must also interoperate with other systems. His claim was that vendors such as SAP SE, ServiceNow Inc., Salesforce Inc. and Workday Inc. have “always had their semantics,” but historically they “jealously guard it just like their source code.”

He argued that is changing. As evidence, he pointed to SAP’s work harmonizing its data model across its application portfolio and packaging it into what SAP calls data products – assets that cannot simply be exported, but can be shared while remaining “resident inside SAP.” Baer positions this as central to the SAP-Databricks relationship, emphasizing that these are “two fiercely independent companies,” and that the mechanism is relevant.

The panel pressed him to “cut to the chase,” and talk about OSI. OSI is the Open Semantics Interchange framework – which Baer likened to the Open Systems Interconnect model, intended to make semantics portable and interpretable across parties. In Baer’s view, OSI enables one organization to define something such as “customer” and have another system interpret it as intended, effectively aligning definitions. He said OSI is based on a framework developed by dbt Labs Inc. and is “kind of like exposing a metric store.” In his opinion, OSI “wouldn’t be happening” unless semantics were becoming central to defining a large portion of the context used by AI systems.

Baer also noted two adjacent movements – early progress “at the edges” on ontologies (which he positioned as a natural outgrowth), and interesting work such as what Microsoft is doing in Fabric IQ. But the headline prediction was directional – semantic spheres of influence are not just emerging; in 2026 they will be solidifying, and those spheres will shape how organizations use data and AI.

Tony Baer’s bottom line is the semantic layer is the most actionable “next step” the industry can take and more gettable than context graphs. The winners will use semantics not only to standardize metrics, but to extend interoperability and durable influence across ecosystems in the AI era.

Dave Menninger agreed with Baer on the importance of semantics and context for AI success, but added a caution. He referenced his team’s data and AI study, saying the No. 1 data challenge organizations face is data usability for AI, and that semantics and context are part of that challenge (though not the entire issue). Menninger acknowledged progress in that multiple vendors claim semantic-model support and many are announcing OSI support.

His critique focused on the mechanism most of these efforts use – SQL as the language for capturing semantics. In Menninger’s view, SQL is “not sufficient” to express the business rules behind how most businesses operate. Without a richer expression language, he argued, it’s not possible to provide all the context needed by AI systems. His conclusion was semantics are becoming a popular investment and progress is real, but the industry still has “a ways to go” before the problem is solved.

Panel comments reinforced that semantic layers are both old and newly relevant. One comment argued that today’s semantic models are not dramatically different from what used to be called OLAP cubes decades ago, and that their value is that when many data sources create ambiguity, semantic layers provide an abstraction layer and a single set of definitions – preventing LLMs from “playing fast and loose” by choosing among competing interpretations. In that sense, semantic layers are a practical guardrail because LLMs “have a bad habit” of making up meaning unless definitions are explicit.

Semantics are seen as a “good baby step” toward full context – going beyond metric stores to include dimensions, categories and entity definitions (product, customer, order). But the group also emphasized what semantics doesn’t cover, including temporal elements and richer relationships, echoing Menninger’s concern that SQL is not enough. Still, the panel view was that semantic layers are an intermediate step that many customers haven’t even taken yet and that those who have already established semantic hygiene are ahead for AI, even before launching major initiatives.

Watch the prediction led by Dave Menninger.

Dave Menninger’s 2026 prediction focused on a market tension he believes is about to become more prevalent: Agentic AI demand is accelerating faster than commercial software tooling can reliably support, creating an opening where services providers – especially global system integrators – thrive, even as traditional software-as-a-service vendors feel pressure.

Menninger’s prediction began with a reality check. He agreed the industry is making “great advancements,” but emphasized that key capabilities “take time” and “we’re not there yet.” At the same time, “agentic AI is everywhere,” and one of the most immediate places it is showing up is inside software platforms themselves. Menninger noted that vendors are embedding agents into their products to automate tasks or help users accomplish work, and he said that approach is “going pretty well” and “being successful.”

The harder problem, in his telling, is the leap from embedded product agents to generic agent capabilities that can do anything across any organization. That, he said, is “a real challenge.”

He supported the point with adoption data from his survey work. In a survey across roughly 1,200 use cases, about 32% are in production – up from about 15% a year ago – which implies that two-thirds are still not in production. Menninger tied that gap directly to the constraints discussed throughout the panel, and he added a particularly concrete point in that the tooling stack required to build and operate agents at scale is not yet mature.

To quantify that tooling readiness, Menninger cited a ratings exercise across “several dozen vendors” in AI platforms:

He posed the question How can you build agents and deploy them if you don’t have the basic tooling in place to support those agents? The conclusion he drew was that commercial off-the-shelf tooling is not ready for prime time. He reinforced the point with an example from a same-day vendor briefing suggesting the roadmap sounded strong, but the capabilities were still “planned” and “not in the market yet.”

That leads to the economic and competitive implication that with agentic AI “all the rage,” enterprises are not waiting for packaged tooling to catch up. Menninger said his research shows custom tooling is the second most common tooling used for AI applications right now, which naturally confers advantage to organizations that can design, integrate and operationalize bespoke solutions. He contrasted what customers hear from application vendors – citing SAP touting “150 Joule Agents” embedded into business applications – with what system integrators are doing behind the scenes.

Based on visibility his colleagues have into service providers, Menninger said, the GSIs they meet with have built hundreds and in many cases thousands of AI agents. These vary in complexity, but he emphasized that most are more focused than a general-purpose tool would need to be, enabling faster production outcomes. Because they do not have to “boil the ocean,” they can bound the problem, ship faster and deliver value to enterprise customers more quickly.

In Menninger’s view, enterprises needing working agentic outcomes now, paired with immature commercial tooling, sets up 2026 as a year where service providers thrive and SaaS vendors get squeezed, not because agents are failing, but because the operationalization burden shifts value toward those who can integrate, tailor and deploy.

Kevin Petrie agreed with Menninger’s assessment pointing to his research which shows integration complexity is a major barrier to success with agentic workflows. He argued that many organizations understand that to get real benefits, they need to bring functions together into multistep agentic workflows, and that requirement is “tailor-made for SI assistance.”

Petrie also cited data pointing to “tailwinds” for consulting firms and SIs, referencing a recent report by Shawn Rogers and Merv Adrian. The key finding he surfaced was that satisfaction levels are higher with external consulting firms than with internal IT departments. He acknowledged this is “not unprecedented,” but emphasized it reinforces the idea that SIs have substantial value to add as enterprises attempt to stitch together agentic workflows across systems.

Watch the prediction led by Kevin Petrie.

Kevin Petrie’s 2026 prediction was a direct challenge to private investment enthusiasm related to OpenAI’s reported $100 billion raise. OpenAI is a higher-risk bet than the market is pricing, and it could trip up. Petrie anchored the prediction in an historic pattern he says he has seen repeatedly during innovation booms – rapid adoption and excitement can cause both technologists and investors to lose sight of fundamental risk.

Petrie framed his skepticism through personal career context. He started as a financial journalist in the dot-com era, watching metrics such as “eyeballs matter more than profits” eventually collapse. He drew a second comparison to 2005, when retail investors viewed collateralized debt obligations as a risk-reducing path into mortgages – another case where risk fundamentals were misunderstood. The point was not that history repeats exactly, but that human nature repeats. In boom periods, risk is underweighted until it suddenly isn’t.

From there, Petrie argued that one doesn’t need an MBA to become concerned about OpenAI – just “the numbers” and the magnitude of the company’s aspirations. He acknowledged OpenAI’s “dazzling success” and cited several scale indicators: 700 million users, which he characterized as 8% of the globe as weekly active users, and raising $60 billion, “more than any private company ever.” His central concern was what comes next in that OpenAI “want[s] to raise another $100 billion,” which he called “pretty brave,” noting it would exceed what any company has raised on the public markets.

Petrie then pivoted to how the capital is being used and what it implies about sustainability. He estimated OpenAI had roughly $13 billion in revenue in 2025, with a possible $20 billion exit run rate, but argued losses exceed that. He cited information inferred from Microsoft’s financials and other sources suggesting $11 billion lost in the third quarter alone. He floated a further concern – explicitly calling it speculative – that OpenAI could be losing money “on every inference task,” implying negative operating margins and cost structure pressure.

The bigger strategic critique, in Petrie’s narrative, is that OpenAI is making enormous infrastructure commitments in pursuit of artificial general intelligence that may not match near-term practitioner demand. He said OpenAI has signed letters of intent to add $1.3 trillion of data center capacity to train “super-smart models,” while his data indicates what practitioners want now is data quality, integration assistance and better-trained workers – not AGI. He also claimed OpenAI “owes Oracle Corp. $300 billion,” arguing this creates an uncomfortable situation in that new fundraising may be needed to meet existing commitments.

Petrie contrasted OpenAI’s position with Google’s. In his view, Gemini now has “commensurate” model performance, and Google can fund investments with existing cash rather than relying on massive capital raises. He suggested there are questions about OpenAI’s strategic direction as it makes “massive bets” on AGI while also attempting to learn chip-building and partner with Broadcom to design chips. He argued OpenAI should “draw a little more focus,” and pointed to Anthropic as a comparison. Anthropic, he said, is more focused on safety, fewer safety “blowups” and greater strategic clarity. Petrie also cited profitability timelines – Anthropic “predicting it in 2027” versus “2029 for OpenAI,” as he recalled it.

His guidance for enterprise data and AI leaders was to ask fundamental questions about vendor stability before committing, because the switching costs are rising. Petrie argued it is getting harder to change gen AI models because of metadata tied to capabilities and the ways models must be integrated into governance architecture. The implication is vendor risk increases when switching is expensive, and in his assessment, OpenAI is “much higher-risk” than alternatives such as Anthropic or Google.

Andrew Brust largely agreed that model leadership is fluid but pushed back on the idea that OpenAI’s position can be evaluated purely on current technical standing. He observed that many smart people he knows are using Anthropic/Claude and finding it superior, and even using Claude Code for non-coding tasks as a kind of personal and business AI. But he cautioned that foundation model providers are “leapfrogging each other every few months,” making it hard to pick a winner based on the current moment. He cited Google’s resurgence as an example: many thought Google was behind, and now Gemini is “enjoying a great status.”

Brust also argued OpenAI has a distinctive form of first-mover advantage – brand defaulting. He compared it to “Kleenex” or “Google” as a generic verb. He offered an anecdote that younger users refer to ChatGPT simply as “Chat” (“I looked it up in Chat”), and tied that to the prevalence of shadow AI in enterprises – often ChatGPT – because people started with it at home and are comfortable with it. He suggested this could become influential later.

Finally, Brust drew a historical analogy where Amazon.com Inc. was unprofitable for a long time and looked like a money pit, yet market share and first-mover advantage across commerce markets ultimately won the day. The implication is that long periods of losses do not automatically disqualify a company if it can convert adoption into sustainable advantage.

The panel’s comments pushed the debate further. For example, Amazon became profitable in retail, but its real margins came from AWS – an “act two.” Without AWS, Amazon might have been “a bigger Walmart.com.” That comment suggested the real question for OpenAI is whether it can build a comparable adjacent profit engine, and whether current initiatives (for example, shopping) show evidence of that. Another comment questioned monetization more bluntly in that broad usage is not the same as paid usage (“Is he paying for it?”).

Additional panel discussion introduced usage data that complicates the competitive analysis. In a reference to the same 1,200-use case dataset, while “custom” was the second most common tooling, the most common tooling was ChatGPT. Gemini and Claude had roughly one-third the usage of OpenAI in that sample.

The other question posed: Is OpenAI is “too big to fail?” — reinforcing the idea that scale and default status can create resilience independent of near-term profitability. Though it’s unlikely the government would save OpenAI if it ran into deep trouble, it’s quite possible that the industry collectively (Nvidia Corp., Microsoft and others) would step in.

Other panel comments expanded on the cost debate, suggesting inference costs are likely to decline materially as infrastructure improves, which could change unit economics over time. At the same time, the panel returned to the sheer magnitude of the revenue trajectory implied by OpenAI’s ambitions, describing the required growth as “mind-boggling.” Indeed some forecasts show OpenAI exceeding $300 billion in revenue by the end of the decade.

After some debate, we gave Petrie the last word on his prediction. He closed with a clarification that his claim about negative operating margins on inference was speculative. He attributed the source to Ed Zitron, a commentator known to be “a bit of an AI skeptic,” who wrote in November that his estimate was that OpenAI’s inference costs exceeded revenue to date for that year. Petrie offered that as context for the concern, not as a definitive financial statement.

Overall, Petrie’s prediction boils down to a warning that OpenAI’s adoption and cultural cachet are undeniable, but the scale of capital, commitments and strategic breadth introduces a risk profile that data and AI leaders cannot ignore – especially as switching costs rise and governance architectures harden around chosen vendors.

Watch the prediction led by Andrew Brust.

Andrew Brust’s 2026 prediction was a wakeup call, warning that enterprise AI will stall this year – not because models aren’t ready, but because governance isn’t. In his view, capability is accelerating “gangbusters” while controls are lagging and enterprises cannot tolerate that widening gap for long. The result is experimentation surges, pilots ship, but scaled deployments slow down or reverse when risk increases.

Brust’s argument starts with enterprises having standards around foundational controls, and he contends agentic AI is now moving faster than those controls can be built and operationalized. The critical missing pieces he highlighted were concrete mechanisms around controlling levels of autonomy, workflow approval, lifecycle governance and the ability to test agents before deployment. Until those are in place, Brust argues, many of the productivity gains being discussed – across semantics, context and agentic workflows – remain largely theoretical. His reasoning is that without discipline, “pretty much anything runs rogue,” and if agents run rogue, they will get deployed and then rolled back because “the liabilities are just going to be too broad.”

Sanjeev Mohan’s follow-up didn’t dispute governance as a blocker but it challenged the idea that governance stops the train. Mohan’s view was that AI is “flowing everywhere” and “you cannot stop it,” so businesses will work around governance gaps by choosing use cases with lower embarrassment risk, lower blast radius and fewer crisis scenarios. He argued that 2026 is likely to be the first year since ChatGPT’s release where the industry begins to show real progress on governance – precisely because the risk is now too obvious to ignore.

Mohan gave credence to Brust’s prediction, however, and cited a briefing with a major vendor earlier in the day, in which governance questions hit hard, and the vendor effectively admitted they were not as far ahead as they wanted to be – and that “there’s really nothing out there yet.” In Mohan’s opinion, that admission is itself evidence that governance is behind the market’s capability curve, but also that the industry is beginning to treat it as a first-order problem.

From there, the discussion broadened into a set of reinforcing panel comments that converged on a central theme that enterprises don’t deploy agents; they deploy systems of accountability and agency. One comment emphasized “gravity” – adoption will lag until vendors ship governance that matches the enterprise risk profile, and even when organizations push deployments forward, disillusionment will trigger slowdowns if agents can’t be controlled in a disciplined way. Another comment reframed the moment as “some assembly required” – like a child’s Christmas gift – suggesting governance won’t stop deployments outright, but enterprises will have to address missing pieces themselves before production is viable.

The panel also surfaced other practical nuances. There was broad agreement that the agentic wave is still early – agents only entered mainstream discussion roughly 18 months ago – and that it’s unrealistic to expect maturity now. The more grounded expectation was that agents will appear first in well-defined, self-contained processes and special-purpose roles (including examples such as agents for data science), while claims of near-term, broad “agentic transformation” across enterprises are likely overstated. Related comments suggested that much of what’s being counted as “agents in production” may actually be agentic features inside existing software, rather than autonomous multistep workflows operating across systems.

A final thread that emerged alongside governance was that the enterprise opportunity is real, but the blockers are multidimensional. Panel comments pointed to data quality rising to the top of obstacles over the past year and a half, alongside the “people problem” – for example,, training workers and building an operating model for consistent enterprise usage. The panel also noted signals that knowledge-worker AI usage inside enterprises may be declining – attributed to job-security anxiety, lack of focus, and the absence of replicable processes – further reinforcing the idea that governance and operating model maturity are prerequisites for successful deployment.

In sum, Brust’s prediction underscores a universal truth in enterprise tech in that lack of governance produces risk, and risk produces stall. Nonetheless, the consensus view is AI won’t pause for governance, so enterprises will navigate around the gap with bounded use cases while the industry builds the accountability systems that scaled agentic AI requires.

Thanks to the panel for the thoughtful predictions. We’ll be back next year to rate our accuracy and look ahead to an exciting second half of this decade.

Support our mission to keep content open and free by engaging with theCUBE community. Join theCUBE’s Alumni Trust Network, where technology leaders connect, share intelligence and create opportunities.

Founded by tech visionaries John Furrier and Dave Vellante, SiliconANGLE Media has built a dynamic ecosystem of industry-leading digital media brands that reach 15+ million elite tech professionals. Our new proprietary theCUBE AI Video Cloud is breaking ground in audience interaction, leveraging theCUBEai.com neural network to help technology companies make data-driven decisions and stay at the forefront of industry conversations.