City of Paradigm: Crowdfunding delivers community as well as funds

![]() Below is an excerpt from Kyt Dotson’s novel City of Paradigm, a science fiction tale about a fictional 21st century city situated somewhere in California. Each City of Paradigm column is two parts: an excerpt from the novel and an editorial describing the real-world context of the technologies described in the story. Readers may find more City of Paradigm here on SiliconANGLE.

Below is an excerpt from Kyt Dotson’s novel City of Paradigm, a science fiction tale about a fictional 21st century city situated somewhere in California. Each City of Paradigm column is two parts: an excerpt from the novel and an editorial describing the real-world context of the technologies described in the story. Readers may find more City of Paradigm here on SiliconANGLE.

![]() “Horizon Softworks started as an idea between myself and Oliver Kosma about how customers interact with virtual worlds in video games,” CEO Felicia Sterling told the sleepy-eyed men sitting around the conference table in the uncannily cold room.

“Horizon Softworks started as an idea between myself and Oliver Kosma about how customers interact with virtual worlds in video games,” CEO Felicia Sterling told the sleepy-eyed men sitting around the conference table in the uncannily cold room.

As she spoke, she clicked a remote in her hand, shifting a slideshow through increasingly saccharine, bright images of happy people and sci-fi space vistas. “The massively multiplayer game genre has seen a lot of big players recently from Blizzard to CCP Games, but we think that we can give gamers a more compelling, persistent, living world by harnessing the computing power of modern day artificial intelligence.”

Ordinarily, Jimmy Ito would accompany such a presentation but she needed him on a much more important project. Before her arrayed three representatives from the VC firm Apollo Venture—or perhaps two representatives and a secretary, Sterling could scant recall the terse introduction outside the elevators an hour before. The representatives arrived in the middle of the worst part of the storm and she met them personally to bring them in from the bleak weather. The scent of rain still followed the group everywhere in the building even though umbrellas and wet overcoats had been dropped haphazardly on the empty chair at reception.

Still, Sterling would not allow some unseasonable rainstorm to dampen her spirits, or the presentation.

“Does anyone have any questions?”

“I hear that you have an extraordinarily small team for the project that you’re undertaking,” said Cameron Hoop, he had introduced himself as a junior associate when she’d greeted him at the door. Sterling had set a meeting with their head executive, Vance Apollo, but instead of arriving himself he sent these henchmen. She wasn’t sure if there was an intended slight in the last minute change of plans, but Mr. Hoop assured her that he could make decisions for the firm if needed.

Sterling paused a moment as she thought about her answer. She folded her arms and nodded, using the remote clicker to raise the lights in the room—the presentation could wait.

“Since coming out of stealth only two months ago, our little crew has grown from thirty-five to eighty-nine people,” she said.

The man sitting next to Hoop opened a small folder, water stains from the rain still visible on its edges, and handed it to him. After a long moment of scanning the page, Hoop looked up again and adjusted his glasses.

“It says here that your company controls almost five million dollars in technological assets, split between servers, services, datacenters, and employees. Blizzard has over 4,700 employees over three different cities, it took 500 people to launch World of Warcraft. How do you expect to make Ex Astris a blockbuster with such a small team?”

Sterling smiled. Hoop had put her right in her element and even without Ito or her co-founder by her side she felt confident enough to lay all their cards on the table.

“Horizon Softworks will be one of the world’s first mostly-virtualized companies in 2014 and we put modern day technology to its full use for this. Our small team is able to raise small armies of small-task employees by leveraging the capacities of projects such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and for everything except major content components we hire on freelancers to build out new resources supervised by our in-house content team.”

The screen flickered behind her as she clicked to a new slide. “We even have a built-in customer base now with our fully funded three million dollar Kickstarter for Ex Astris. By utilizing crowdfunding, we have an entire batch of beta testers who have paid at least box price to play the game in its alpha stage. They work in tandem with our content team to continually develop and release new features as we build towards the end product. Between testers, freelancers, and Turks my small team is agile enough to rapidly develop, deploy, and prepare new projects.”

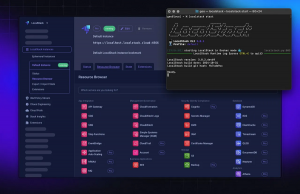

“To do this, we will be leveraging cloud-based virtual workstations that allow us to quickly change over the nature and use of entire floors of our building to suit the needs of our current development process. This section of the building currently houses the graphics department who work with multiple consulting teams across the world to build and incorporate in-game assets. In less time than it would take to eat breakfast, I could have this entire floor’s workstations ready for a team of developers to produce an entire new game mechanic.”

Hoop nodded. “I also saw that you have licensed the services of OC Lollipop from Fuji Interactive, but you have her listed as a consultant and a service rather than a media asset. Doesn’t she make music and act in audio-visual media?”

Sterling nodded sagely.

“OC Lollipop is the lynchpin of our model and the reason you all had to sign a non-disclosure agreement before we let you on premises,” she said gravely. “What I’m about to tell you represents the secret sauce of what we expect to make Ex Astris the next blockbuster MMO to hit the market.”

After taking a breath, Hoop closed the folder in front of him and slid it back to his companion. “Mr. Apollo rarely signs NDAs with new companies. Tell me, why should we be ‘wowed’?”

“The software developed to run Lollipop’s capabilities that makes her such a compelling actor and musician is active only on Fiji Interactive’s servers, however, with the assistance of a small team of Artificial Intelligence experts and a brilliant mind from MIT named Jimmy Ito, we have been able to virtualize and hyper-parallelize the software into a cloud exoscale platform,” Sterling said. “In short, OC Lollipop will become the customer-facing capability of Ex Astris providing performance for millions of non-player characters in game, personalizing the experience for every player, and giving life to what would otherwise be a sterile virtual world filled only with voice actors and scripted events.”

“Ex Astris and Horizon Softworks through our game studio, Angular Horizon, will singlehandedly revolutionize an experiment in expert systems by showing that AI-as-a-service isn’t just possible: it’s an inevitability in the consumer entertainment market. Add in all the volunteers from our successful crowfunding round currently training our AI to understand our core players and the launch product will understand the player base better than any other video game in history.”

– Excerpt from The City of Paradigm, novel by Kyt Dotson, © 2014

The story segment above is all about Ex Astris seeking investment, but one big takeaway is that the little fictional startup is already well on its way to the big leagues via leveraging crowdsourcing. The now-famous Kickstarter web page gets mentioned while CEO Felicia Sterling explains her startup’s current financial status. Previous segments examined AI-as-a-service, also mentioned, and how customers interact with developers.

Kickstarter has become a seed source for projects that otherwise might not have found the light of day in the “traditional” publishing scene. Notably, going the crowdfunding route has other benefits than simply providing funds to seed or continue a venture. Crowdfunding itself is a social experience that opens up markets, connections, provides focus, and even builds a community around a project. Most successful Kickstarters end up carrying away all of these secondary-benefits and it can have a real effect on the developer or startup that used the platform.

Only about 40% of all Kickstarter projects successfully receive funding (Kickstarter stats.) This is in part because on Kickstarter only projects that reach or exceed 100% funding receive any funds at all.

The numbers from the Ex Astris crowdfunding are a bit absurd: $3m is an unlikely goal for an unknown developer. To date, only 66 successful Kickstarter projects have made in excess of $1m, making up less than one tenth of a percent of all successfully funded projects. One of the most recognisable would be Star Citizen–which made $2m on Kickstarter–and is very similar to the fictional Ex Astris.

Of course, not all crowdfunding ends (or begins) with Kickstarter and Star Citizen has continued to crowdfund and has already exceeded $46 million with continuing crowdfunding by selling not-yet-available in game assets.

To get an idea as to how going to Kickstarter affects the development of a new project I asked the teams of three different successful Kickstarter games about their experience. MyDream produces an MMORPG with creative elements; Cubical Drift made Planets3, a sandbox game that looks like Minecraft, but with planets; and Son of Nor from StillAlive Studios, an adventure game with puzzle solving.

For all three of my examples, none of their teams started with Kickstarter in mind, but eventually sought crowdfunding for some extra funds. In each case, they did come out with the needed funds but also something extra: increased focus and a community of backers.

MyDream

![]() Allison Hunyh, Founder and CEO of MyDream, and Mark Davis, one of the lead developers, tell a story of starting out with some initial money and effort that gave them enough to get the prototype for the game produced. When it came time for the team to consider further funding, Kickstarter looked like not just a good place to get funding, but also give the game a market test.

Allison Hunyh, Founder and CEO of MyDream, and Mark Davis, one of the lead developers, tell a story of starting out with some initial money and effort that gave them enough to get the prototype for the game produced. When it came time for the team to consider further funding, Kickstarter looked like not just a good place to get funding, but also give the game a market test.

But beyond a market test and some money, MyDream found community and focus on Kickstarter.

“It was amazing,” MyDream says about their Kickstarter experience. “There was a great community of other game developers and gamers. We made a ton of contacts, learned a lot about messaging and marketing and came together internally as a company. Those are things that people usually pay for, but instead, we were able to get all that and raise over $100k.”

As for focus, MyDream says that getting a Kickstarter going gave the team a renewed vigor. The need to present the project in a particular way, market it to potential supporters, gave them a reason to simplify development and stick to a workable core.

The success of the Kickstarter gave MyDream a band of eager fans that the team now feels compelled to make sure they provide the product supporters have paid for.

MyDream aimed for $100k and ended up making $117k. For more information about the game–a sandbox-styled MMO with RPG elements–read up about the Kickstarter announcement on SiliconANGLE.

Planets3 from Cubical Drift

![]() Cubical Drift’s founder Michel Thomazeau says that Kickstarter was actually his second solution for Planets3, approached only after failing to reach “classical” investors. The game had been in development for almost one and a half years, but it was time to find a way to move on to the next stage.

Cubical Drift’s founder Michel Thomazeau says that Kickstarter was actually his second solution for Planets3, approached only after failing to reach “classical” investors. The game had been in development for almost one and a half years, but it was time to find a way to move on to the next stage.

Since Planets3 is a project started by Cubical Drift without the influence or patronage of a publisher the developers could go wherever they wanted with it. Going with Kickstarter meant that instead of attempting to woo an investor, they needed to attract gamers.

“On Kickstarter the approach is really different in comparison of traditional investors,” Thomazeau said. “You don’t need to make financial projections, but you need to really convince with your own product, with your own trailer and team.”

To reach Kickstarter readiness, Cubical Drift focused on making a working prototype of the game, which meant eschewing gameplay and mechanics for having a fundamentally sound product.

With a successful Kickstarter, Cubical Drift now has the breathing room to plan for the future and enough money to put the team on the project full time.

Cubical Drift aimed for $250k and ended up making $310k.

Son of Nor from StillAlive Studios

![]() Chris Polus from StillAlive Studios says that Son of Nor started out humbly with the team hoping to build the game by themselves and with their own money. As time went on, however, it became obvious to the team that this could not be sustained. So they turned to Kickstarter.

Chris Polus from StillAlive Studios says that Son of Nor started out humbly with the team hoping to build the game by themselves and with their own money. As time went on, however, it became obvious to the team that this could not be sustained. So they turned to Kickstarter.

“One could say Kickstarter made us put things into the game that we would not have put there if we hadn’t made this campaign,” says Polus about the experience. “On the other hand this might have been what Son of Nor needed.”

In the same way MyDream found focus when going to Kickstarter, StillAlive, it seems, found Son of Nor. In order to win hearts (and wallets) in the Kickstarter campaign, the StillAlive team realized they had to appeal to the gamers who would fund them. To do this they had to revisit the basics of the game and rekindle what made the game fun to play.

The renewed focus meant a different sort of development. One that centered on the community rather than the go-it-alone self-driven process from before.

“It is a little bit of extra effort. Sometimes it takes a week to finalize a build,” says Polus. “But then again it forced us to confront player’s feedback and build something for a release and play it ourselves to see if it’s any good. We are now forced to test our game over and over and not push testing back until the very end.”

Polus adds, “I find the pressure turns out to be a good metering tool of our own quality and product, even if it’s not always comfortable.”

StillAlive Studios aimed for $150k on Kickstarter and nailed it at $151k; but much like Star Citizen, StillAlive is continuing to take donations.

Kickstarter comes with a dose of community

In the story segment, CEO Sterling mentions that Ex Astris intends to tap into what she calls a “ready made” community of backers from the Kickstarter. This is because every successful Kickstarter builds a community of people who have a literal investment in the wellbeing of the project they supported.

Star Citizen’s continued success after their Kickstarter highlights this as a perfect example. Trading on a well known industry name, plus a highly successful Kickstarter (or other crowdfunding), means the initial “crowd” doesn’t just go away after the initial funding but remains while the product is developing.

MyDream’s sentiment went even further than just backers in finding that other developers engaged with them during the Kickstarter–opening up connections they hadn’t had before.

As well, in every case, the presence and expectation of that community led every team to find focus and emerge with a plan to wow their backers.

Image credits: “MyDream logo”, MyDream (c) 2013 (second image on page); “Earth”, Cubical Drift (c) 2013 (third image); “Son of Nor”, StillAlive Studios (c) 2013 (forth image).

A message from John Furrier, co-founder of SiliconANGLE:

Your vote of support is important to us and it helps us keep the content FREE.

One click below supports our mission to provide free, deep, and relevant content.

Join our community on YouTube

Join the community that includes more than 15,000 #CubeAlumni experts, including Amazon.com CEO Andy Jassy, Dell Technologies founder and CEO Michael Dell, Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger, and many more luminaries and experts.

THANK YOU