NEWS

NEWS

NEWS

NEWS

NEWS

NEWS

Fictiv Inc. is bringing 3D printing just a little bit closer to the mainstream.

The San Francisco-based contract prototype manufacturing firm that specializes in additive technology (also called 3-D printing), is taking its service national and has added computer numerical control (CNC) production capability to its lineup. CNC is the subtractive technology similar to that used in most manufacturing environments, in which raw materials are whittled down to finished products. It’s considered a late-stage complement to additive manufacturing.

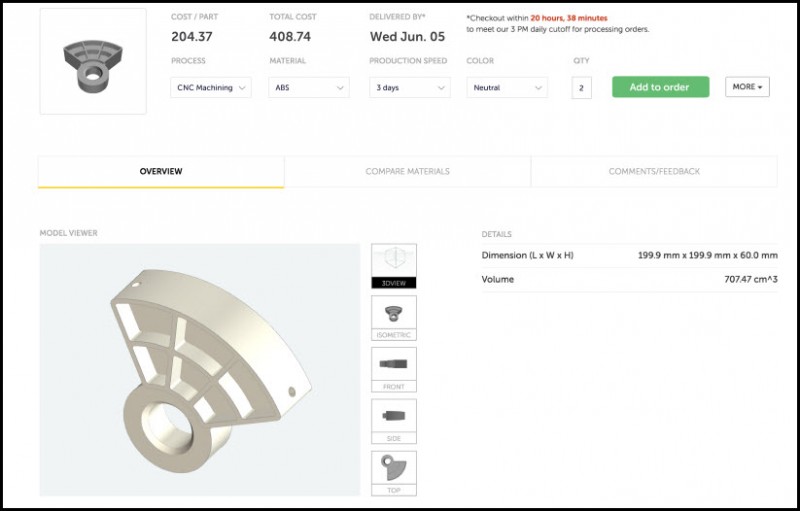

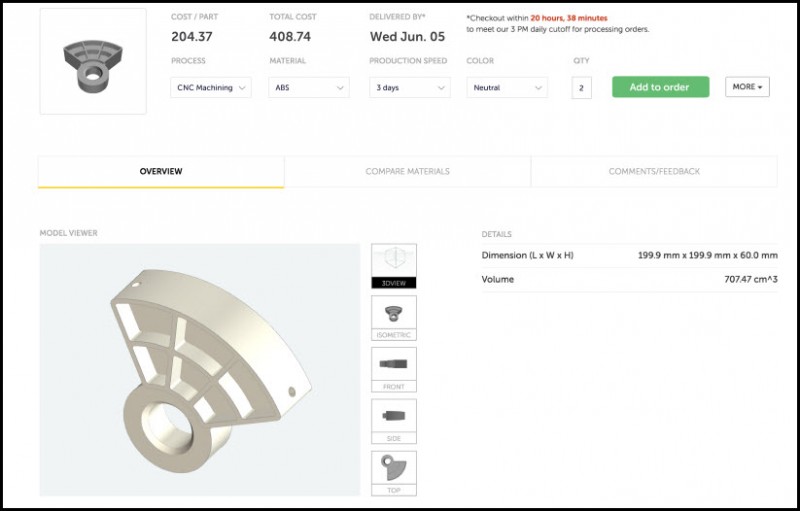

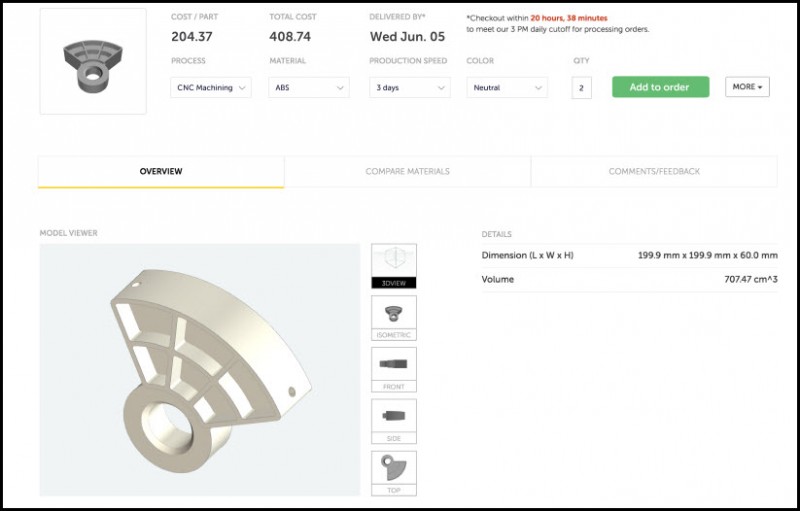

Fictiv uses a network of 3D printing and CNC machines to enables customers – who are primarily engineers – to more easily fabricate hardware prototypes. Users can upload computer-aided design (CAD) files to Fictiv servers and the company delivers 3D-printed prototypes in 24 hours and CNC machined parts in three days.

Co-founder Dave Evans got the idea for the service while working at Ford Motor Co.’s Silicon Valley Lab. A Stanford University mechanical engineering graduate, he was fascinated by the possibilities of bringing 3-D printing – which had long been available only to well-heeled corporate giants – to the mass market. Evans and his brother, Nate, founded the company in 2013 to serve the local Bay Area market, but are now taking the service national.

3-D printing services are nothing new. Companies like 3D Hubs B.V., 3D Systems Inc. and Sculpteo SAS provide them directly or connect networks of 3-D printer owners to share and exchange jobs. However, those services are more oriented toward the enthusiast or maker audience. Fictiv targets industrial designers.

In line with that, the company provides a lot of back-end support, including professionals who analyze designs for validity and cost. Customers can upload an optional part drawing for producing tight tolerance, complex parts. After an order is placed, Fictiv’s platform intelligently matches each part to an immediately available machine among its network of individually vetted vendors for rapid production.

The company can build models using four different plastic resins – Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), nylon 6/6, polycarbonate and Delrin 150 – as well as aluminum and stainless steel. It can also work with rubber and transparent plastic materials.

Additive and subtractive technologies serve different functions in the design process, Dave Evans explained. Additive technology is most useful in the design stage when quick, but not very functional, prototypes are needed. Subtractive technology comes to bear when a part is further down the design pipeline and needs to be tested for strength and manufacturability. Subtractive prototypes are closer to the finished product than additive ones.

In contrast to some of the hype surrounding 3-D printing, the technology has is limited because of the nature of the materials used. Most 3-D printers work with melted metal or plastic, which limits strength and precision. “If you think of how a 3-D part is made, it’s not as structurally strong because of the limitations of materials or tolerances,” Evans said. “Additive is good is in low-volume, high customization situations, but you’re not going to see a 3-D-printed iPhone in our lifetime.”

The company has raised venture capital but Evans wouldn’t disclose the amount.

Support our mission to keep content open and free by engaging with theCUBE community. Join theCUBE’s Alumni Trust Network, where technology leaders connect, share intelligence and create opportunities.

Founded by tech visionaries John Furrier and Dave Vellante, SiliconANGLE Media has built a dynamic ecosystem of industry-leading digital media brands that reach 15+ million elite tech professionals. Our new proprietary theCUBE AI Video Cloud is breaking ground in audience interaction, leveraging theCUBEai.com neural network to help technology companies make data-driven decisions and stay at the forefront of industry conversations.