CLOUD

CLOUD

CLOUD

CLOUD

CLOUD

CLOUD

In 2013, IBM Corp. got a wakeup call when it lost an important cloud computing deal at the Central Intelligence Agency to Amazon Web Services Inc.

IBM protested the contract, exposing previously confidential details. In a high-profile decision, Judge Thomas Wheeler ruled against IBM despite the apparent higher bid submitted by AWS. The bottom line: AWS’ cloud offering was viewed as superior to IBM’s.

Less than 24 months into her tenure as IBM’s chief executive, Ginni Rometty (pictured) understood the imperative. IBM had to make a move to get into the public cloud game or it would be left out in the cold, much like Hewlett Packard Enterprise Co., Cisco Systems Inc., EMC Corp., VMware Inc. and other large tech firms at the time. IBM paid $2 billion to acquire SoftLayer and has since transformed the platform into a viable offering from which it intends to rewrite the cloud narrative.

Here’s a paraphrase of the premise put forth by Rometty at this week’s IBM Think conference in San Francisco:

Chapter one of the cloud represented about 20 percent of the workload opportunity. It was largely about moving a lot of new and customer-facing applications to the cloud. Chapter two is about the hard stuff. It’s about scaling artificial intelligence and creating hybrid clouds. It’s about bringing the cloud operating model to all those mission-critical apps and enabling customers to manage data, workloads and apps and move them between multiple clouds. This is a trillion-dollar opportunity and IBM intends to be No. 1.

IBM is not alone in its aspiration. Large companies such as Cisco, VMware and even HPE have somewhat similar aspirations. As does ServiceNow Inc. and a host of smaller specialist firms. And of course, the public cloud giants, including AWS and Microsoft Corp., have their own ideas about chapter two of the cloud era.

To claim a leadership position in this next chapter, IBM is spending $34 billion to acquire open-source software leader Red Hat Inc. This is a huge move on the chessboard, underscoring that the IBM Cloud and a decade of trying to commercialize the AI-powered Watson system aren’t enough to win the day. Rather, it sees open source, Kubernetes, containers, microservices and developers as a lynchpin to success in the next chapter of cloud.

There’s much debate about who first created the term cloud computing. There’s little doubt, however, that AWS evangelist Jeff Barr’s blog post in the summer of 2006, announcing AWS’ Elastic Compute Cloud, ushered in the modern era of cloud — chapter one. In his post, Barr wrote:

With Amazon EC2, you don’t need to acquire hardware in advance of your needs. Instead, you simply turn up the dial, spawning more virtual CPUs, as your processing needs grow.

His assertion underscored the most fundamental value proposition of cloud: Pay only for what you use. This of course was the first of numerous innovations and functions — all available with the swipe of a credit card, to be dialed up on demand. Startups flocked and tapped world-class data center services previously available only to large companies.

The economic downturn of 2007-2009 led chief financial officers to mandate a shift from capital expenditures to operating expenses, and when the economy turned up, businesses realized that their cloud experience enabled much greater agility. Shadow information technology powered the next phase of growth and as “cloud creep” permeated the market. IT departments hopped on board and haven’t looked back.

Notably, Microsoft transformed itself to the cloud using the formula of: 1) An open-source mindset with alignment and support on open compute, Linux on .Net and the like; 2) cloudifying all things Microsoft and making Azure, not Windows, the center of its universe; and 3) bundling office 365 to show revenue from not only infrastructure and a service but software as a service.

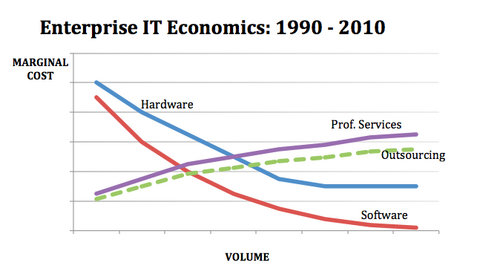

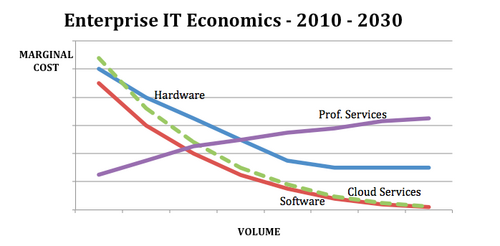

Joined by Google, which used its dominant global search infrastructure to stake its claim in cloud, the big three paved the way for a new economic model based on scale, innovation and automation, applying software economics to the concept of infrastructure deployment and management services (figures below).

Key points in the charts:

Before diving into the Red Hat piece of the puzzle, we have to point back to data. In our view, IBM is working closely with customers to build a digital business fabric where data remains the underpinning of its strategy to drive a new era of analytics based on AI. IBM sees data as a fundamental ingredient to bringing contextual relevance to business applications. What we’re seeing is because of IBM’s massive services business and deep industry expertise it has earned the right to help customers build digital networks and transform business models.

IBM’s large customers are getting this. They’re not looking to IBM to simply deliver services or secure their infrastructure or sell them SaaS. Rather, they’re looking for IBM to help them transform and deliver new business models. We’re seeing this in healthcare, financials services, agriculture, energy, insurance and virtually all industries in which IBM has a presence globally.

IBM’s opportunity as we see it is to help companies understand how to make money using data — not necessarily by directly selling their data but figuring out how to monetize data. What we see IBM doing is taking what have been largely piecemeal, data-oriented AI projects and creating what Rometty calls “Outside/In”: customer experience oriented applications and “Inside/Out” — that is, workflow and new ways to work applications — both which contribute to bottom-line results. More importantly, IBM wants to help customers completely transform their business operations.

To accomplish this, IBM is delivering a business platform fueled by data and a machine intelligence platform, meaning tooling and capabilities to extract value from data and operationalize AI.

IBM didn’t release any new details about Red Hat at Think, presumably because of regulatory concerns. But with Red Hat, IBM can enable a new breed of application developers — for businesses — using cloud-native tooling. Data is the key ingredient to emerging business applications, and with Red Hat in its portfolio, IBM can “cloudify” and “data-fy” businesses and position itself as modern and relevant. More importantly, it can dramatically scale Red Hat’s business globally.

Red Hat for IBM emerges as a vehicle for generating derivative leverage out of IBM ecosystem software and industry knowledge. With RHEL, OpenShift and 8 million Red Hat developers, IBM can help its customers modernize their application portfolios and transform business operations — creating a new breed of digital business developers.

Consider statements made by Rometty and Red Hat CEO Jim Whitehurst during their mini-roadshow after announcing the Red Hat acquisition. Rometty kept saying, “This isn’t a backend-loaded deal.” What did she mean? In our view, she was essentially explaining the business case for IBM paying a 60 percent-plus premium over Red Hat’s stock price prior to the deal being announced. Specifically, IBM has a huge installed base of services clients (a $20 billion-plus captive opportunity in our estimate) at which it can point Red Hat PaaS tooling to modernize application portfolios and build the future digital business platform for and with customers.

So out of the chute, IBM can immediately begin scaling Red Hat’s business, marrying deep industry expertise, the sprawling IBM SaaS portfolio and where applicable the IBM Cloud, AI-infused everywhere, and Red Hat platform as a service to connect customer data, workloads and applications to any cloud or on-premises installation.

Longer-term, IBM can, along with its clients, fully adopt modern application development practices to codify its deep industry expertise and build out transformative business and AI platforms to help incumbent companies compete in the digital era.

If you don’t own a public cloud, you go hard after multicloud. To wit: VMware exited public cloud after years of trying to commercialize VCloud Air. It finally settled on a deal with AWS and sold off its public cloud. VMware is Dell’s ace in the hole for multicloud.

Cisco recently announced its multicloud strategy at Cisco Live Barcelona that comes at the problem from a strong position in networking. As networks flatten, Cisco can be the glue between clouds with a software management and orchestration framework for networked data — not a bad strategy. HP tried and failed in the public cloud game and HPE is trying to be a provider of multicloud services, but it’s largely relying on packaging its hardware, services and some minimal software content.

Of these players, only Cisco has any meaningful presence with developers. IBM with Red Hat gets access to 8 million devs.

As a result, IBM has a stronger position than these players — albeit more complex. It owns a public cloud presence and though not nearly as large as AWS in IaaS, IBM has a large SaaS portfolio. Like Oracle, it doesn’t have to compete for commodity business against AWS. Rather it can sell value “up the stack” using SaaS as a high-value play. As well, its AI runs in the cloud and it just announced at Think that it’s opening up Watson to run on any on-premises, public or hybrid cloud (a long overdue move in our opinion). Previously, if you wanted Watson, you could only get it on IBM’s cloud.

Microsoft clearly will have its say in chapter two of the cloud. With its acquisition of GitHub and its large software estate, combined with a leading cloud at scale, Microsoft holds a lot of cards. It is investing in AI and has a strong data angle.

Google Cloud is resetting with new management and is playing the long game. It clearly has AI chops and a strong data angle.

Then there’s AWS. Amazon’s announcement of Outposts shows that it can and will evolve and change its spots. Today, AWS makes a strong case for a single versus a multicloud approach — arguing that multiple clouds are less secure, more complex and more expensive. While credible in its position, the reality is multicloud is like multivendor. There’s not a procurement czar inside every company that will dictate a single cloud. As such, if AWS sees an opportunity to manage multiple clouds it will enter the space, in our view.

The new “innovation cocktail” combines Data + AI + Cloud. A common data model brings competitive advantage in a digital world. Machine intelligence, or AI, applied to data drives insights and cloud enables scale and attracts innovation through ecosystems. IBM is combining these three elements to compete in the next chapter of technology industry growth.

IBM, like Microsoft, is cloudifying its offerings to support its clients’ digital transformations. By bringing cloud to its products, building data networks with customers, applying AI everywhere and leveraging Red Hat, it can catalyze a new class of business developers and go hard after the multicloud opportunity that exists.

We believe, however, that the multicloud world will be messy. Today, multicloud is as much a multivendor occurrence as a deliberate strategy. Nonetheless, buyers will continue to choose horses for courses — meaning the right cloud for the right workload — and that will inevitably lead to multiple clouds and opportunities for simplified management, security, governance and data leverage.

Today, about half of IBM’s revenue comes from so-called Strategic Imperatives. That piece needs to grow faster than the other half declines. Moreover, about 60 percent of IBM’s revenue comes from consulting and professional services. The good news there is that it gives IBM deep visibility and relationships into virtually all global industries. The downside is that business doesn’t scale as well.

As such, IBM’s greatest strength is also its greatest challenge. The unique opportunity facing IBM is to codify that deep industry expertise in software, using data as the key ingredient for new business applications built on cloud native PaaS tooling and scaling to the cloud — any cloud.

That is a differentiating story and one that protects IBM from getting “Amazon’d” while at the same time allowing the company to drive margin improvements over time. Rometty has spent the last five to six years preparing the company for this next chapter. Now Big Blue needs to show that elephants can dance, sprint and run marathons.

Support our mission to keep content open and free by engaging with theCUBE community. Join theCUBE’s Alumni Trust Network, where technology leaders connect, share intelligence and create opportunities.

Founded by tech visionaries John Furrier and Dave Vellante, SiliconANGLE Media has built a dynamic ecosystem of industry-leading digital media brands that reach 15+ million elite tech professionals. Our new proprietary theCUBE AI Video Cloud is breaking ground in audience interaction, leveraging theCUBEai.com neural network to help technology companies make data-driven decisions and stay at the forefront of industry conversations.