POLICY

POLICY

POLICY

POLICY

POLICY

POLICY

Technology generally and Big Tech specifically are regularly cited by politicians, media and governments around the world as the root of many societal problems today.

Accusations such as privacy invaders, fake news amplifiers, job destroyers, discriminators and more are commonly lobbed at technology firms with little recognition for the substantial value large tech companies have delivered over the decades. Moreover, many powerful government officials have rewritten the history of effective government oversight and are attempting to apply antitrust law in novel ways that have virtually killed mergers and accquisitions and threaten to stifle American exceptionalism and innovation.

In this Breaking Analysis, we welcome David Moschella, CUBE alum, author and senior fellow at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. Moschella and Robert D. Atkinson have written a new book, parts of which we’re going to explore today: “Technology Fears and Scapegoats, 40 Myths About Privacy, Jobs, AI and Today’s Innovation Economy.”

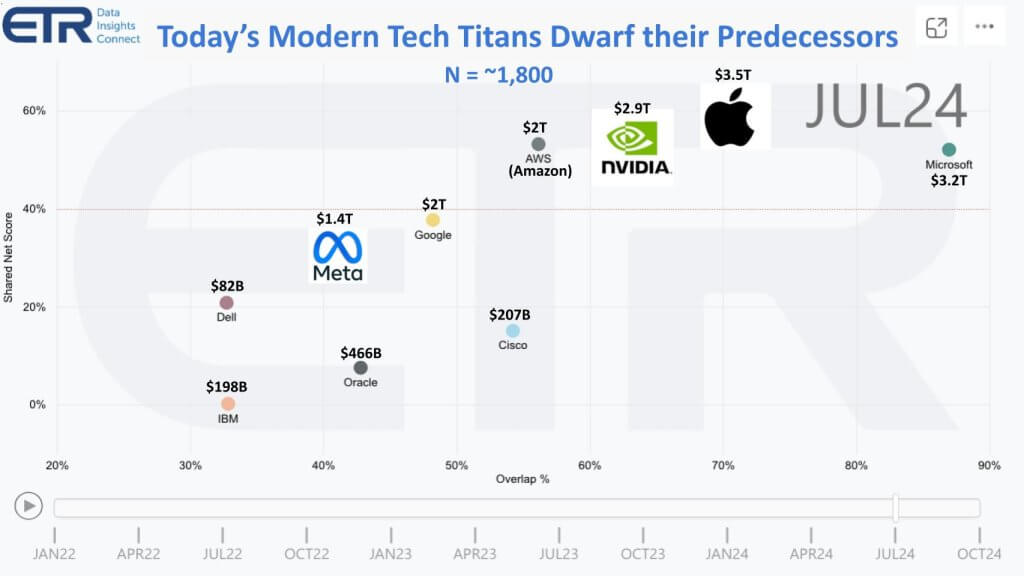

We’ve cherry picked seven of the 40 myths that we’re going to dig into today. But before we do, let’s take a quick look at some of the spending data from Enterprise Technology Research to frame the conversation. If you watch this program, you’re familiar with this format where Net Score or spending momentum is on the vertical axis and penetration into the data set is on the X axis. The red line at 40% indicates a highly elevated spending velocity.

ETR focuses on the enterprise, so we’ve superimposed the logos of those firms we don’t track and along with the valuations. There are six with market caps in excess of $1 trillion as of this morning: Meta Platforms Inc., Google LLC, Amazon.com Inc., Nvidia Corp., Apple Inc. and Microsoft Corp. And the point is that these firms now dwarf to a large degree the valuation of past leaders such as Dell Technologies Inc., IBM Corp., Cisco Systems Inc. and Oracle Corp., whose combined value is less than $1 trillion.

Q1. These six trillionaires take a lot of shrapnel and are often the targets of the vitriol. Now, importantly, we’re not saying monopolies that break the law should be allowed to do so. Absolutely not; and in your book, you and Rob Atkinson said that you wanted to lay out the facts and a balanced view of the issue. But please describe in your own words why you and Robert wrote the book.

Moschella: Thanks, Dave. And yeah, like you, I’ve spent my whole career in the technology business and for the vast majority of that time, people were very optimistic and had favorable views of our business, particularly those of us who were up in Massachusetts where tech sort of revitalized the economy here and then later helped America defeat Japan in the electronics business and all the benefits and great things that have happened through the internet.

But really starting around 2017 with both the election of Trump and the Brexit referendum in the U.K., perceptions of our business started turning negative and it’s actually been getting worse for the last six or seven years so that people want to ban things like facial recognition or something like AI comes out with all of its incredible potential and yet 90% of the stories are about the downsides and risks and what to so-called do about AI.

So Rob Atkinson and I really tried to take this head on. And we basically came up with a list of 40 things that people say all the time about the tech business and really have come to define pretty much today’s conventional wisdom. And we wanted to see how well they really hold up to a reasonable scrutiny. And we’re not saying that these fears, these complaints, these scapegoats are wrong.

But we are saying that often, they’re more wrong than right. And in many cases they’re highly exaggerated. And so the book is really a way to walk through that. The book is called “Technology Fears and Scapegoats” because sometimes that’s sort of the generic fear that people have of the future.

And other times, people are just looking for scapegoats of who to blame for all the problems that we have in the world, be it polarization, misinformation, bias, discrimination, job loss, all these things and people looking for something to blame. Unfortunately, tech gets far more of its share than deserves. So yeah, the book basically tries to make that case and, as you say, give a more balanced perspective on really what’s happening.

There are 40 myths in the book and we don’t have enough time to go through even half of them. The authors penned 20 each and we’ve highlighted six of our favorites.

[Listen to David Moschella on why this book, why now?]

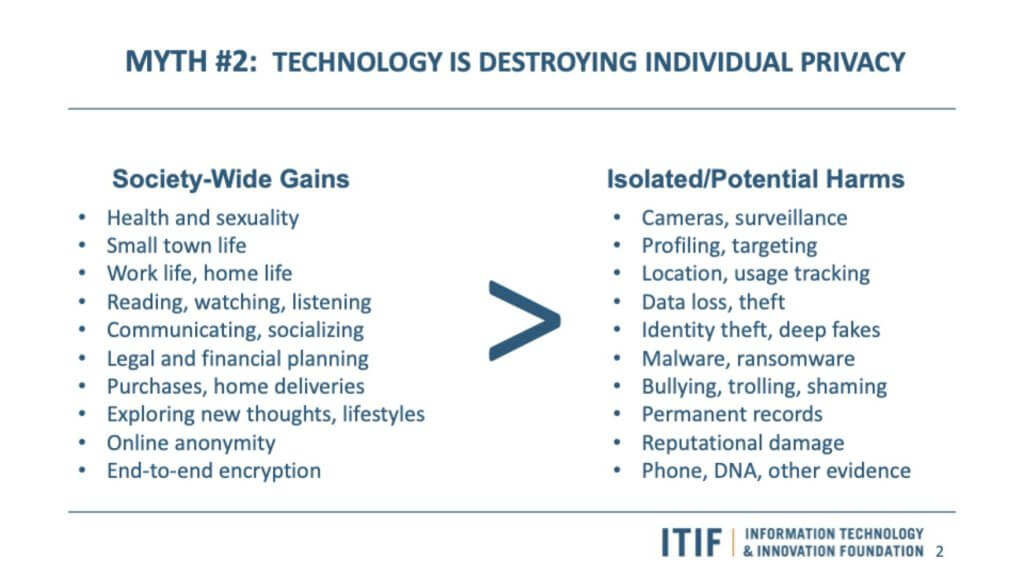

The first one we’ll explore is Myth No. 2 in the book, Technology is Destroying Individual Privacy. The premise put forth in the book for this myth is that despite the issues the media often points to about privacy concerns, technology actually has built in a lot of controls into its products and services.

Q2. In the book you write that technology has created far more privacy than it has destroyed. Yet the sentiment against Big Tech in this regard is universal. Please explain the myth.

Moschella: Yeah, it’s a classic. What people often forget is that before technology and before the internet, most people had no privacy whatsoever. If you lived in a small town, basically everybody knew your business at the local pharmacy, the local shop or the local bookstore or whatever. If you wanted to look up some sensitive issue about health or sexuality or gender or beliefs, there were very few places and often times no cases where you could do that in any sort of confidential manner. So the internet has essentially brought massive amounts of privacy to virtually every American.

How many of us have never searched on something that you did because you’d rather not talk about it with someone else and you wanted to get some information. And we all do that. And when we do that, we’re essentially making a bet and we’re betting that, all right, the servers at Google or Amazon or whatever, they might in some ways know what we’ve asked, but the odds of that coming back to embarrass you or hurt you in any way are very, very small.

So people make that bet, and by and large, it’s been an overwhelmingly winning bet. And that isn’t to say that there aren’t real privacy risks with today’s technology. We all know this. Cameras are everywhere, there’s lots of surveillance, we’re profiled, we’re targeted. Our locations are tracked. Data is retained forever. China shows us every day what a surveillance state could look like.

But if you compare those and you say, “All right, hundreds of millions, virtually every American and really billions of people around the world benefiting from the confidentiality of a standard search versus a smaller number, it’s hard to say exactly how many, but in my view, at least one order of magnitude, probably two orders of magnitude of people actually hurt in any serious privacy way, you see that the balance is overwhelmingly positive.” And yet you almost never read a positive story about the internet’s ability to increase privacy.

The organization I work with, the ITIF, they’re a digital policy organization and we spend a lot of time in Washington. And when you listen to the way, say a congressional hearing talks about privacy, they treat a Musk or a Zuckerberg or Google folks, treat them like criminals of basically abusing people’s privacy to make money and almost never a good word. And I like to say, well, if just once they might start one of those hearings by saying, we’re really grateful for all the privacy that technology does create in our lives, the ability to read something without everybody knowing what you’re reading or to watch something rather than go to a video store and rent a DVD. That all of these forms of privacy that are created, people should appreciate those.

And then, OK, let’s focus on, we don’t want to be like China. We don’t want to surveil everything. We don’t want to keep data forever and have it so that the worst thing you’ve ever done, it might be what shows up on a Google search about you and those sort of real issues. But they’re manageable as long as we keep in context that the overall situation is not just positive but overwhelmingly positive.

[Listen to Moschella explain how tech has done more than people realize to protect privacy.]

Q2a. A couple followups. Is it correct to assert that credit card companies have a lot of information, even prior to the internet, that they collect on us? Are there restrictions on credit card companies or the kind of animus toward those companies and the financial institutions that possess similar data on us? How is that protected and why do you think that that’s not been as much of an issue?

Moschella: It’s clear that the information business is a really complex ecosystems of banks, credit card companies, governments, healthcare organizations, insurance organizations, law enforcement, all kinds of people with all kinds of data out there. So why does tech get singled out? I think it’s pretty clear. They get signaled out because they have the money and they have the power. They have the visibility.

But those other firms that you mentioned, they’re really in the business of trading that data. The Big Tech companies, yeah, they want to sell ads, but their primary business is to get people to use their services. So I think they get way more of the blame than they really deserve.

And even if you ask people, would you pay for this service or would you rather get it free with ads, the overwhelming share of people say, “I want it for free.” And people who’ve tried to make a $20 a month service for this or that, it’s tough going. And that may change. There are certainly people out there who want to take on the advertising model and that’s part of the tech competition and business. But thus far, consumers really like free. Who doesn’t?

Moving on to the next Myth No. 3 in the book: Social Media is Polarizing America.

Q3. All right, moving on to the next myth. It’s No. 3 in the book. Social media is polarizing America. The conventional wisdom here is that social media certainly amplifies our divisions and creates this flywheel effect that exacerbates polarization. Is that not the case? Please explain your thinking on this one.

Moschella: The privacy myth is one of a fear. It’s an issue where people are worried about that. This one to me is overwhelmingly an issue of scapegoating that, when people try to say, “Why is America so polarized?” it’s so easy to blame it on social media. But the reality is, we’re polarized for real issues. Donald Trump is a uniquely polarizing figure, whether you like him or not. The country is deeply divided over abortion and guns and immigration and climate change. Our political system is a 50-50 tribal system that clearly leads to a polarization built into that. You have the mainstream media, whether it’s Fox News or CNN, they’re polarized themselves and contribute to this.

So there are all these real sources of polarization. And to me, they’re actually extremely similar to what America was like in the 1960s. In the ’60s, America was incredibly polarized by an unpopular war, by assassinations, by riots, by protests, by drugs, by the counterculture, and all of these things. And all of those polarization happen without any social media whatsoever. You look at Trump, Trump was polarizing whether he was on Twitter or kicked off of Twitter. It made no difference really at all. And so I think a lot of it is scapegoating, but as you say, yes, social media amplifies it. People say more harsh things sometimes when they can be anonymous.

Filter bubbles and algorithms and these things have their place and there’s propaganda and fake news. All the things are out there, but to me they really are sort of drops in the bucket compared to the main issues. And so why are we so focused on social media? I think it’s primarily a question of scapegoating and convenience. What’s more appealing to politicians or mainstream media than saying, “Well, the problem isn’t us. The problem is this new stuff.”? And in fact, you could easily title this section, Mainstream Media Agrees that New Media is the Problem. It’s basically just shifting the blame to the newcomer or the new way. And that’s a familiar pattern, but I don’t really think it really holds up to scrutiny.

[Listen to Moschella’s explanation of the real issues around polarization.]

Q3a. When you think about nation state hackers, the big four are China, Russia, North Korea and Iran. They are using social media to foment dissent. And of course then there’s the TikTok piece, which is quite interesting and we’ll see what happens there. You’ve always been a proponent of approaching that from the standpoint of, hey, if you’re going to not allow our platforms to participate in an open way in China, then you can’t do so in the United States. Any thoughts on these two points?

Moschella: Yeah, two things here. The TikTok thing, as you say, although I’m generally in favor of all kinds of free speech and open platforms, in this case where the situation is so unbalanced that Google and Facebook and X cannot operate in China. So why on Earth would we allow TikTok to operate here? It’s a simple matter of fairness and reciprocity.

You don’t even have to get into all these national security things, which in many cases, I think are exaggerated. You mentioned the Russia and China and Iran and North Korea and yeah, they try to interfere with elections, but I’ve got news for you, we try to interfere with people’s elections all time around the world. To me, this whole storyline goes back to the election of Trump where so much of it was blamed on Facebook and Cambridge Analytica and Russian bots and all of these things. And I think most of that, the impact of those efforts has been largely debunked, but the myth lives on.

I’ll just give you one fact on it. By most estimates, people think that Russia perhaps spent $100,000 or $200,000 on bots and various propaganda efforts that they made. Well, the campaigns spent over a billion each to get their message out. So you either have to assume that it’s a drop in the bucket or Russia’s so much smarter and somehow is using things so much more effectively. And there’s no reason to think that. I think, again, this was primarily a way for, in this case, the people on the losing side of the election to find this scapegoat. Why did we lose? We lost because of Cambridge Analytica and Facebook and Russian bots and all of these things. And I think that is just people just kidding themselves.

Stealing secrets and ransomware those are much, much bigger problems without question. And we’re not very good at that. We do change the subject matter onto things that inflame people for little reason without taking actions on the things that really matter.

[Watch and listen to what’s the right approach to Tik Tok according to David Moschella.]

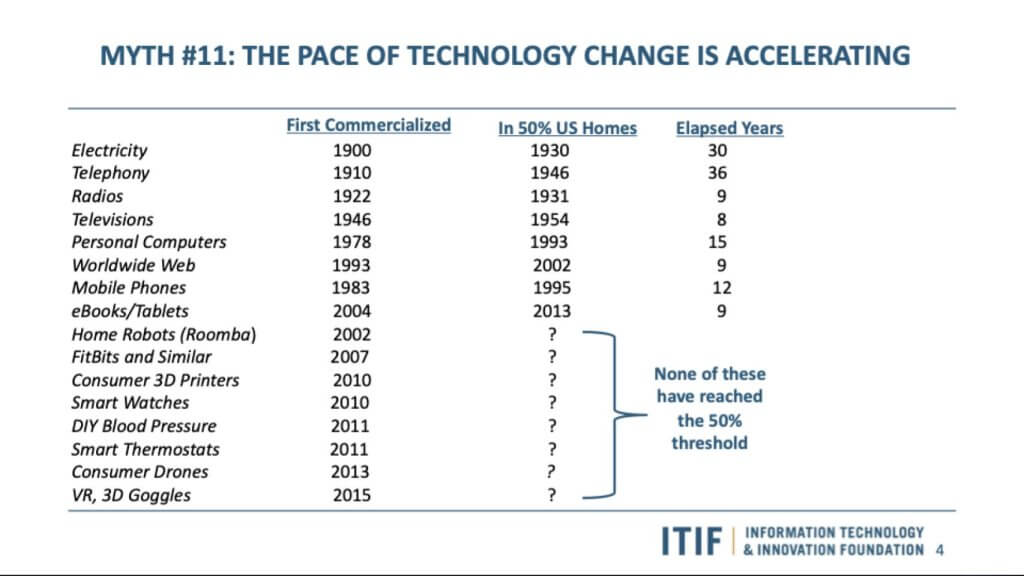

Next we move to Myth No. 11 in the book: The Pace Technology Change is Accelerating.

Q4. This one was a bit surprising because today we’re seeing new large language models come out daily, the number on Hugging Face is nearing a million. But your angle on this comes from one of user/societal adoption. Please walk us through this somewhat contrarian analysis.

Moschella: A standard way of looking at the pace of change for any particular technology is just ask how long does it take for half of the people to have this device? And if you look at that over all the things you see [on the chart above], starting with electricity and phones and going up to the 3D goggles, what you see is a very consistent pattern.

The first two there, electricity and telephones, it took a long time because you had to wire the nation and that was very complicated and very difficult and took many, many years. But since then, if you look at radios and televisions, they were adopted extremely quickly. Within less than 10 years, over half of Americans had them once they were commercially a viable product. Much faster than PCs, roughly the same as the internet, a bit faster than mobile phones.

So if you look at that data, you can’t make really any case that the pace is accelerating and that is strengthened when you look at sort of all the new stuff, home robots, Fitbits, 3D printers, smart watches, blood pressures, thermostats, not one of which has reached the 50% adoption.

So the rate of adoption is not accelerating. But there’s some other ways to look at this question too. Sometimes the sort of companion argument here is that the impact is greater, is accelerating. And that’s not true either, that the tech industry is roughly 60 years old, from the 1960s to today. If you just look at the 60 years before then, the technologies of those 60 years are far more impactful on people’s lives. Electricity and lighting and heating and cooling and air conditioning and movies and telephones and planes and cars and trains and all of these. And you could go on and on and on. Many of us, as it gets hot in the summer, we wouldn’t trade the entire internet for our air conditioners.

And so those innovations of the physical world are clearly more important. I don’t think it’s accelerating and I don’t think the impact is getting greater. And I’ll just throw one other thing out there. Another way of looking at the speed of change is to look at the so-called eras, you know the mainframes, minis, PCs. Each of those eras, mainframes came out in the ’50 and ’60s, the minis in the ’60s and ’70s, the early ’80s, and PCs in the ’70, ’80s and ’90s. And mobile in the 2000s and tens and social in the ’20s and now AI in the ’20s and ’30s. And those eras are all roughly a dozen years each. So even within the IT sector, the pace of major shifts in paradigms is actually remarkably consistent.

So why do people think that it’s getting faster? Well, one of the reasons is they sort of conflate applications with platforms. So sure, ChatGPT gets 100 million people in a couple of months. But why is that? Well, they didn’t have to buy anything. I didn’t have to install anything. I could just go use it. And to me, that’s no different than saying that the Milton Berle show on TV went from no users to 50 million users in a year because all you had to do was turn on the station. And so the applications, whether it’s Facebook or Google or ChatGPT, it’s much easier to put an application on top of a radio program, a television or a computer or the internet than to buy a new platform.

So when people throw those numbers around, it’s like, yeah, that’s great. One hundred million is unbelievable, but it’s because it’s so easy. It was no more difficult than doing a Google search. Billions of people already knew how to do that rather than having to go buy something and learn how to use it. So all of those things, I think, are basically just loads of exaggeration.

Q4a. Do you think that will change? Because as you said, electricity and telephony, you had to put in all this infrastructure, the power grids, the phone lines. Do you think that that will change given that we do have the internet, that we do have all this computing power to leverage? Do you think that the pace will change?

Moschella: I’m not sure I want to make a prediction whether it will or won’t. I’m pretty comfortable saying it hasn’t. And when I look at AI, AI itself, the basic logic of neural networks and machine learning is 60 years old. People understood these concepts in the ’50s and ’60s. It’s taken all that time to become a usable, powerful thing.

And now it’s in its growth phase like an iPhone and everything is flying around it. But it doesn’t mean that AI is a year old and everything’s happened in a year. It took forever to get to this point. And like all of these eras, it has its run of 10 years, and I don’t make any pretense to look beyond that. But I would say this, that as amazing as AI is, and we may get to this later in the talk, the needs and challenges and demands and importance of the physical world is still far more important.

Q4b. So just to understand when you said the tech industry is about 60 years old and AI has been around for at least four decades. So in that case are you saying the clock in your chart for AI would have started 40 years ago? Where would you put AI on this chart?

Moschella: I wouldn’t put it on there because it’s not a device. I would [call that] an application, like “Seinfeld” or “Friends” or “The Milton Berle Show” or Facebook.

The one thing I would say is I think it is true that the impact of the waves gets bigger and bigger. So the impact of the mobile era or the internet era was much bigger than the impact of the mainframe or the mini computer era. And it’s entirely possible that the impact of the AI era will be bigger than the impact of any of the previous ones. That, I totally agree, the impact is greater, but the speed is not.

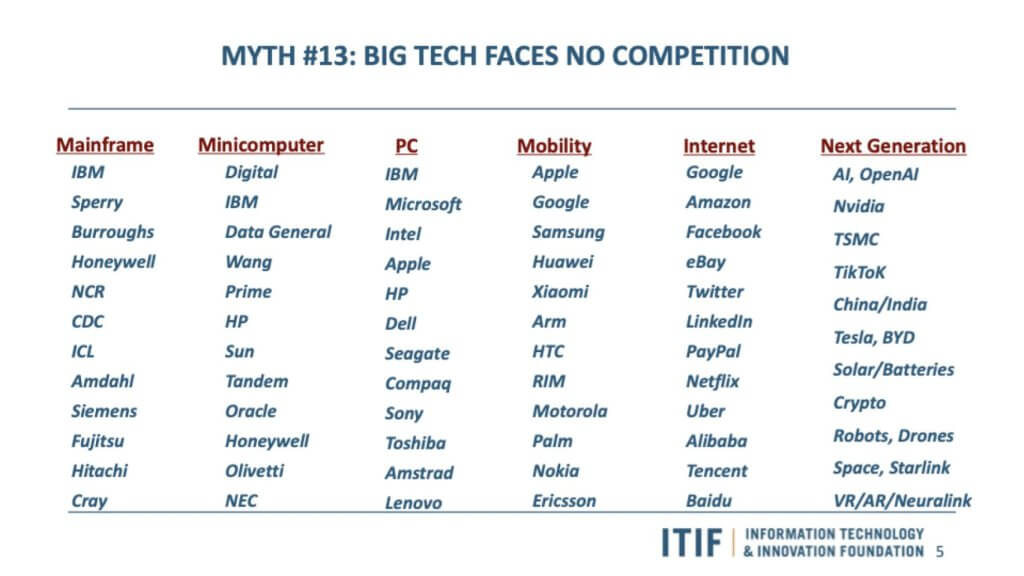

The next one is Myth No. 13 in your book, Big Tech Faces no Competition — that these large companies are just so powerful and insurmountable. You gave a speech in 1995 at the IDC briefing session where you said it felt like Microsoft had reached its peak of power. That’s the year that they were really at the peak with Windows 95 and people thought you were crazy. But it proved correct until Satya Nadella became CEO.

Q5. Below on this chart, you show the leaders of each era and how they come and go. And in the case of Microsoft, they even come back, although somewhat surprisingly you don’t have them in this next-generation column. Walk us through this myth, please.

Moschella: People say that Big Tech faces no competition. They’re being just ahistorical because competition has defined this business. All you have to do is open your eyes to see that a new generation of leaders is already out there. I mean, you see that the list here of companies that have come and gone and some of them lasted an era or two or three, but most of them don’t.

But I think that if you simply look at, all right, who are the leaders of this next generation? Well, AI, it’s Nvidia, it’s TSMC. They didn’t even exist in the previous era. Well, I look at China and India for this all the time. How much of the technology leadership is simply going to [companies in these regions], that weren’t even players in any of the previous eras?

India already today dominates the computer services business probably more than the Asia dominates the hardware business if that’s even possible. And so you look at Tesla and BYD and Crypto and SpaceX and Starlink, the leaders are right there. And yeah, probably you could easily add Microsoft in the next generation and hats off to them for making the recovery and what they’ve done in revitalizing themselves and doing that, which was not an easy thing to predict. And maybe we’ll talk about that more when we get to the antitrust stuff.

But in general, every one of today’s market leaders, the so-called Titans, the Googles, Amazon, they all have serious competition. China is doing everything it can to make it so they don’t need Android phones and they don’t need Intel, and they’re going to pull that off.

Look at what TikTok has done to Facebook. The competition is there. And to me, the key thing on this chart is, here we go again. It’s the same pattern, that it’s very hard for new companies to lead in new areas and we’ll see how Google does with AI and search, and that will be really, really interesting to see how it plays out. But history, you already see, the scenarios for change there are huge.

[Big Tech is defined by fierce competition according to Moschella.]

Q5a. Something you said about China is worth exploring further. Specifically, in the book, you talked about the potential for automation bringing back American manufacturing and the same time you indicated that it’s a hard lesson learned. That U.S. companies became so reliant on China for so much of our manufacturing that it’s problematic. At the same time, others have said, “You know what, China and you outsourcing that manufacturing has really enriched Silicon Valley. It’s not necessarily such a bad thing.” But today we see Huawei basically copying Apple’s format when launching a new phone. They’re high-fiving people as they walk in an all-glass retail store. The associates are clapping as customers enter the store from a long queue. So it seems more insidious than benign, what are your thoughts?

Moschella: I’m glad you brought that up. The book defends the tech business. But we criticize [tech] on three main grounds: 1) a pretty lousy job on security with ransomware, malware and identity and all that stuff; 2) pretty lousy job on protecting kids from harmful content and more could be done there; and 3) a pretty lousy and short-term view of taking all the advantages of globalization and not realizing where that was going to take you; and now finding themselves in a world where they’re completely dependent on Taiwan and China for things that may not be in their interest in the long run. And if there’s anything I would fault the big titans for, it’s not realizing that … they’re global companies, but first and foremost, they’re American companies and need to at least be seen as caring about that issue.

I don’t think they’ve done a very good job of that. That’s become the issue over the last year or two. And it’s just going to become even more of an issue because the China challenge ain’t going away. They’re going to be strong across the board.

It’s not just the question of protecting the American market. The global market is up for grabs in many cases. So I think that is probably their biggest challenge. They can make money today by selling their advanced stuff to China, and they can keep doing that, but is that going to be the right thing in the long run? It’s that general tension between short-term benefits and particularly very long-term ones, and they’ve ridden that China gravy train since China went into the WTO in 2001. So it’s been over 20 years of good times. But it’s not like you couldn’t see this coming.

[Listen to the three main failures of Big Tech according to Moschella.]

This next myth is a favorite. When one opens the book, this myth stands right out.

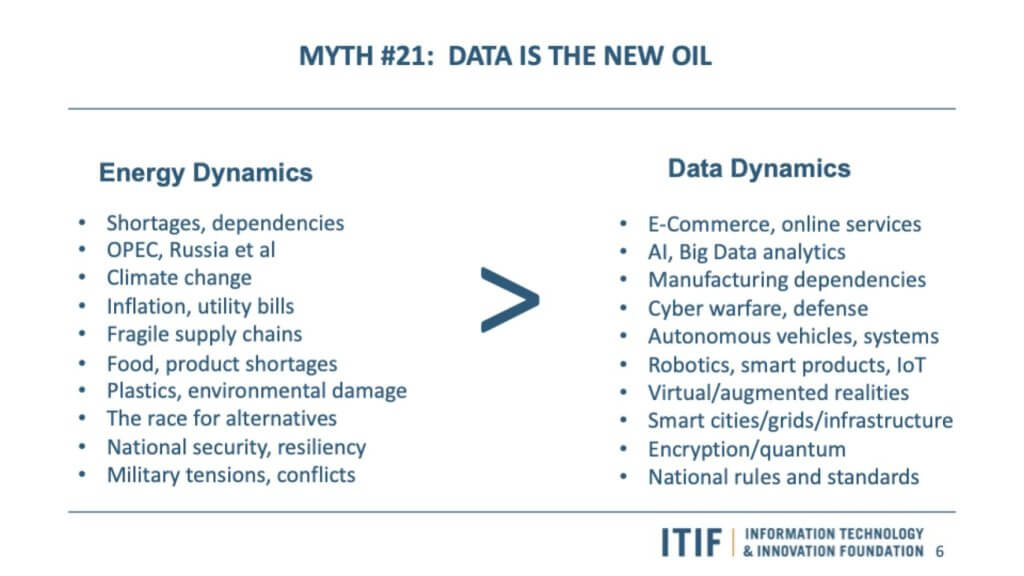

Q6. At first we expected that you would talk about how data doesn’t follow the laws of scarcity. In other words, you can use the same exact data in many ways, but you can only use a fixed amount of oil for one application at a time. You have a far more fundamental angle that you chose to highlight and that is the importance of energy in our lives compared to data. Please explain.

Moschella: Data isn’t [the] new oil. I wish it were true. If only the world revolved around computers and data and information and connectivity and networks, life would be better. But the reality is that energy is still the main force in the global economy. And energy shortages and energy prices lead to inflation and geopolitical tensions and fragile supply chains and environmental issues and race for electrification and electric cars and electric infrastructure and all of these things. In the real world, those things are more important to national power, to national success, and in many cases to wealth than data.

There are all kinds of parallels [between] data and oil, their general purpose, they’ve created great fortunes. They come with so-called externalities. They need to be refined and they can have various side effects and things, and that’s all there.

But in the end, energy is still the most important thing. And if you just look at the electric car and the moving away from fossil fuels issue, there’s nothing comparable in the tech sector that will get society’s full attention. The bottom line, to me, is the physical world of food, shelter, transportation is still more important than the virtual world.

And I’m not sure that will ever really change. People go to war over the physical world. They tend not to [go to war] over the virtual world. I wish it were true. I wish we were in a post-energy, post-oil world, but we are not yet.

[Data is not the new oil…Listen to Moschella’s position regarding this theory.]

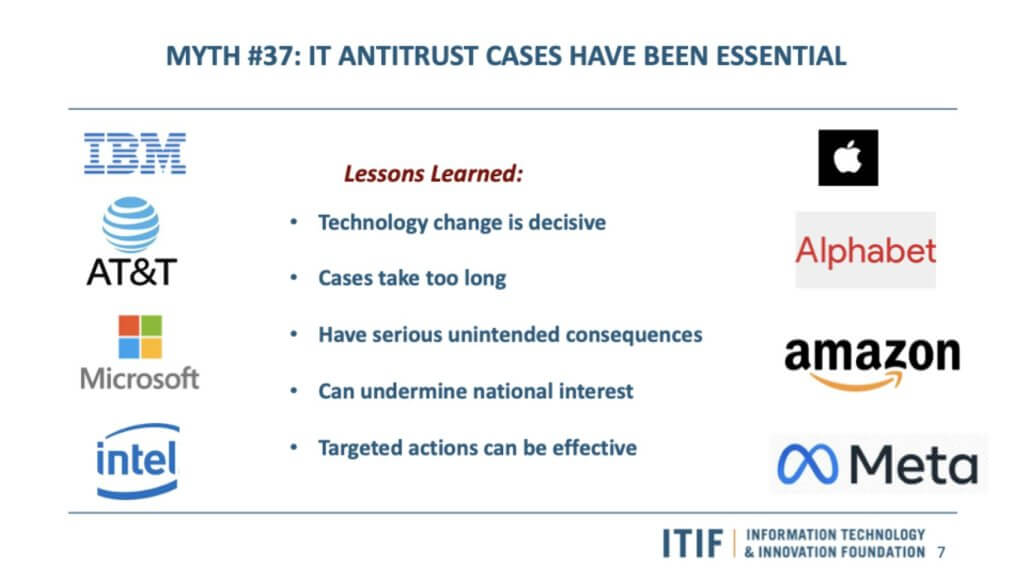

OK, the last myth we’ll touch on today brings us full circle to the intro: Antitrust cases have been essential and by implication successful at regulating Big Tech. This is another favorite as we watch Lina Khan affects the way the Sherman Antitrust Act is applied in novel ways. The point is market forces have been far more successful and effective at regulating Big Tech than broad actions like, for example, breaking up Google.

Q7. Dave, please take some time to analyze the history of government regulation in Big Tech and some of the unintended consequences. And specifically, what remedies do you think actually make sense?

Moschella: First thing is that the IT world has a very, very rich history in issues of antitrust. Why is that? Well, it has to do with some of the unique features of technology that software businesses particularly have and many Internet business have very low or [close to] zero marginal cost so that rewards scale. They’re complicated businesses sometimes, so fear and uncertainty and doubt tends to make strong companies stronger. They have these network effects so that the more people who have them, the more benefits there are. You have all of these sort of industry characteristics that tend to create increasing returns to scale. So having big, dominant companies has been the norm in our business forever, for sixty some odd years.

And every time you get a big, dominant company, someone says, “We need to break them up. This isn’t right.” They may have their case, but there’s so much evidence that indeed you don’t [need to] because technology deals with these problems. People thought IBM was unbeatable, unstoppable, all-powerful and all-knowing and would go on to dominate telecom and banking and factory automation and all of these fields.

But in fact, the simple innovation of the microprocessor, which led to the personal computer, which led to local area networks and then much more, basically obsoleted everything IBM was doing. And that was what took care of IBM’s power. Everybody thought that AT&T monopolized the telecom network and had to be broken up and it was broken up into seven little mini AT&Ts, and people thought that was a great thing.

But what really changed the network? Well, it was the shift to wireless networks. It was the shift to packet switch networks. It was the switch to broadband cable networks. These are the things that brought AT&T down and IBM and AT&T are still successful companies, but they took away any notion of them being monopolies and all-powerful.

And the same thing with Microsoft. If you go back to the ’90s when people used to refer to him as “Tyrannosaurus Gates.” He was going to take over every thing related to technology because he was a predator and he was unstoppable. And then, oh yeah, they missed mobility and oh yeah, they missed the Internet. And they eventually recovered and did great things, but those sectors, they still never really got a position in those businesses of any great significance.

So it was again [similar]. And then there’s Intel, same thing, they have too much control over personal computers and that’s the foundation of everything and everything. Well, of course Intel missed mobile and now it’s missing AI, their position has weakened. But all four are still here. They’re not monopolies and technology change took care of all four of them quite quickly and quite handily.

You look back and did we really need decades-long antitrust suits to do things. And we’ll talk about them, and there are some benefits, but there are also some real unintended consequences that are worth highlighting. If you go back to AT&T, one of the big impacts of the breakup of the Bell system was that each of those regional ones could now buy their telecom equipment from whomever they wanted.

And oftentimes they chose other suppliers from around the world. There was really no home anymore for then Western Electric and then Lucent… Western Electric went from the world’s biggest telecom equipment manufacturer to nonexistent and was actually bought for a song by Nokia. And to this day, America has a very, very small place. It’s dominated by European, Japanese and Chinese suppliers. Same thing with Bell Labs. Once the world’s greatest research center by obviously unanimous views, disappears. No more funding from it in that model. So the AT&T one, especially in Washington, is always cited as a tremendous success.

It is very hard to look back and say that was the case. Yeah, America shifted to wireless and internet, so did everybody else around the world and they didn’t have to do it this way. And the same with Microsoft. That case didn’t last as long, but there was very strong effort to break up Microsoft. They wanted to split the operating systems and applications businesses. And if they had done that, the profitability of both of those groups would have lagged. And the recovery that Microsoft has made and who it is today, you can make a good case, it never would have happened. And that if they had broken them up, who knows what things would look like, but a good chance it wouldn’t be the way it is.

So for the company, for those shareholders, and if you like, what Microsoft has done, which I’m pretty positive about, that scenario is not there. And the same thing with Intel. The government sort of forced Intel to make life easier for AMD and for a long time that actually helped consumers with some lower prices. But it weakened Intel fundamentally, and it also accelerated the fabless view of that business and it reduced Intel’s profitability. And it’s at least partly responsible for the very weakened Intel that exists today. So the unintended consequences are tough, but as you say, there have been some targeted benefits that have been good, and we can go into those if you want.

Just to comment on that: It’s hard sometimes to remember because it was so long ago, the dominance of former monopolies like IBM. At one point, IBM had three-quarters of the industry’s revenue and 50% of its profits. In today’s terms we’d be talking about a $2 trillion revenue company, not market cap, revenue. But in the case of IBM, Microsoft and Intel, market forces and hubris were factors. IBM unwittingly outsourced the microprocessor and the operating system to Intel and Microsoft, respectively. Intel chose not to participate in smartphones initially. Microsoft for its part tried to make Windows phones which no one wanted. Today we have the government talking about breaking up Amazon, investigating Nvidia, which went through major struggles and stock pressure to get to where it is today.

Q7a. But let’s go to those targeted measures because as we’ve said, if a company has a monopoly and is breaking a law, for example bundling or doing things that do violate the Sherman Antitrust Act, they should be punished and there should be remedies. What should those remedies be in your view?

Moschella: There have been remedies throughout the history and sometimes they’ve been very good ones. In IBM’s case, and you, Dave, know this better than anyone, it was government pressure that forced IBM to make it possible for third-party providers of disk drives and tape drives to connect their products to IBM big systems and companies that did that. And that was a really good thing. Unbundling their IBM software really helped establish the software industry. In AT&T’s case, they were forced to allow third-party modems to connect to their network, something they didn’t want to do. They were forced to allow a carrier like MCI to connect to their network, something they didn’t want to do. And similar sort of interoperability things were there with Microsoft and Intel as well.

So the pressure is to open up their platform to make it easier for competitors to have some sort of specifications and standards. These have a pretty good history. It’s the breakups and the threats of breakups and all that where I really draw the line. That, to me, is the big problem that I would have with Lina Kahn, that she believes that bigness in and of itself is a problem and ultimately will harm consumers. I think that’s wrong because as I say, the tech business has increasing returns to scale. So bigness is part of the business and really can’t be taken away. And I still got a problem too with, you had IBM was one monopoly and Microsoft maybe was one, but today they talk about Google and Amazon and Meta and Apple.

They said they’re all monopolies. You can’t have five monopolies. Mono means one. And they all do compete with each other so they’re not monopolies in any sense that IBM would recognize. As you said, IBM had 75% of the entire computer business. That was a monopoly. And so I think I have no issues with the FTC looking at business practices and seeing which ones will help make for a better environment. But when they try to say that they’ve abused this and they need to be broken up and these huge fines and these long cases, those things have not worked so well in the past.

Q7b. What do you make of the Nvidia investigation? Nvidia 15 years ago decided to basically risk everything and start investing in its software platform. It bought Mellanox, and its stock got crushed at times during this timeframe. True, it virtually has no competition. So in that sense, it’s a monopoly, but it has earned it through foresight and maybe a little bit of luck and tailwinds. But what have they done wrong? Do you have any thoughts on that?

Moschella: They’re doing what’s always been there, the leader in their market and everybody gravitates around them for as long as they are the leader in their market. And good on them. So I don’t see it. And you talk about these sort of breakups, there’s nothing more easy and sort of fun with this armchair analysis like, oh yeah, I could break Google up into their phone business and their search business and their documents business and YouTube business. That would be sort of interesting. Oh, maybe Amazon should be broken up. Their cloud and their retail, and Facebook should be broken up.

It’s so easy to see how that might be tempting people, but the history of all those isn’t good. And as you say, at a time when all of those companies are gearing up for battle with China, do you really want to hobble them and weaken them for the hope that it might lead to stronger competition when there’s really no evidence? If you took those pieces apart in Alphabet, do you really think that’s going to strengthen the American competitors? I sure don’t.

[Listen to the unintended consequences of Big Tech antitrust.]

THANK YOU