CLOUD

CLOUD

CLOUD

CLOUD

CLOUD

CLOUD

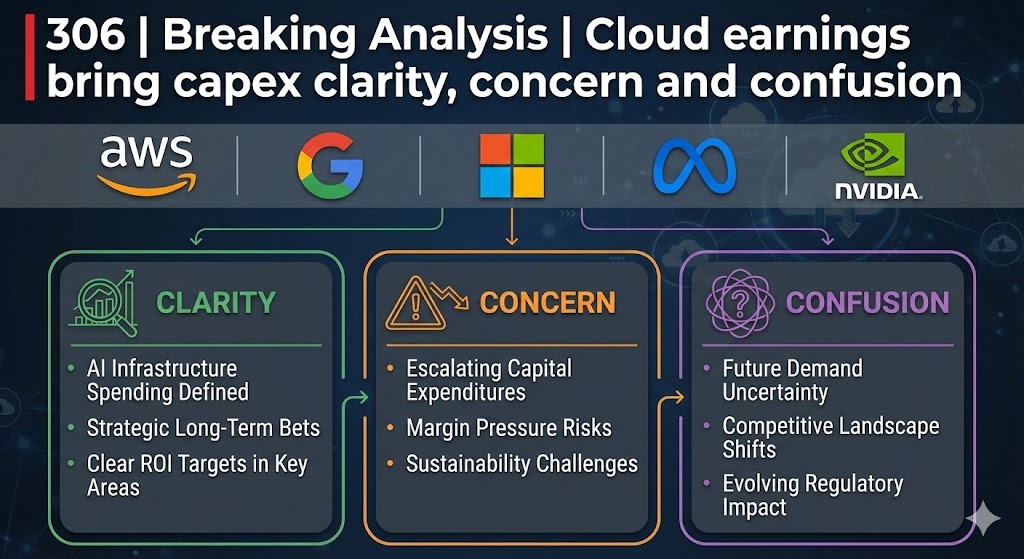

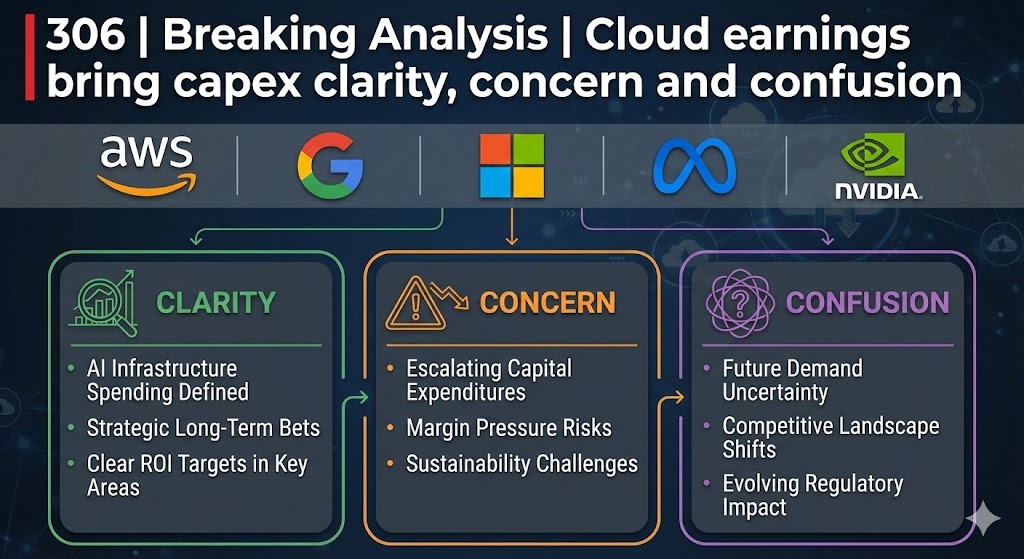

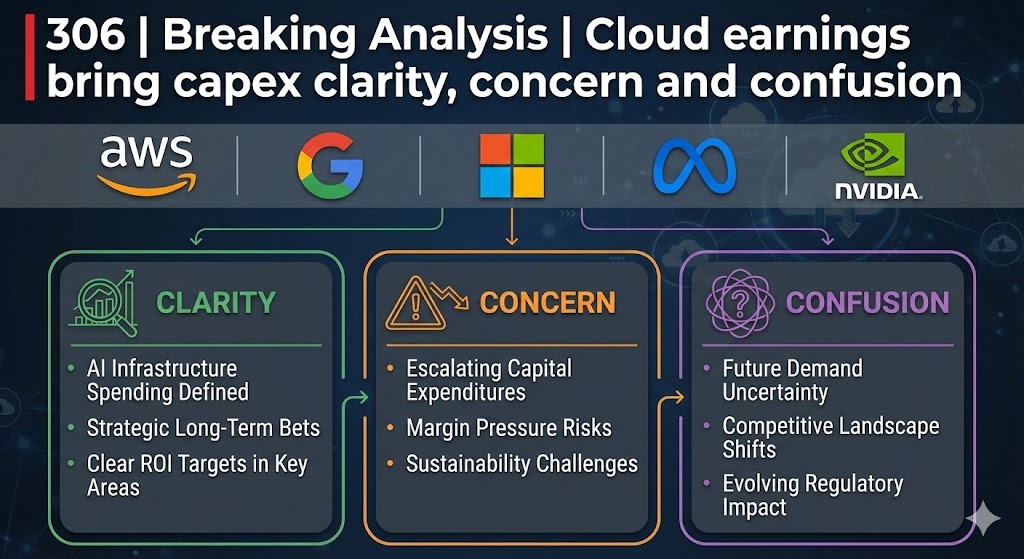

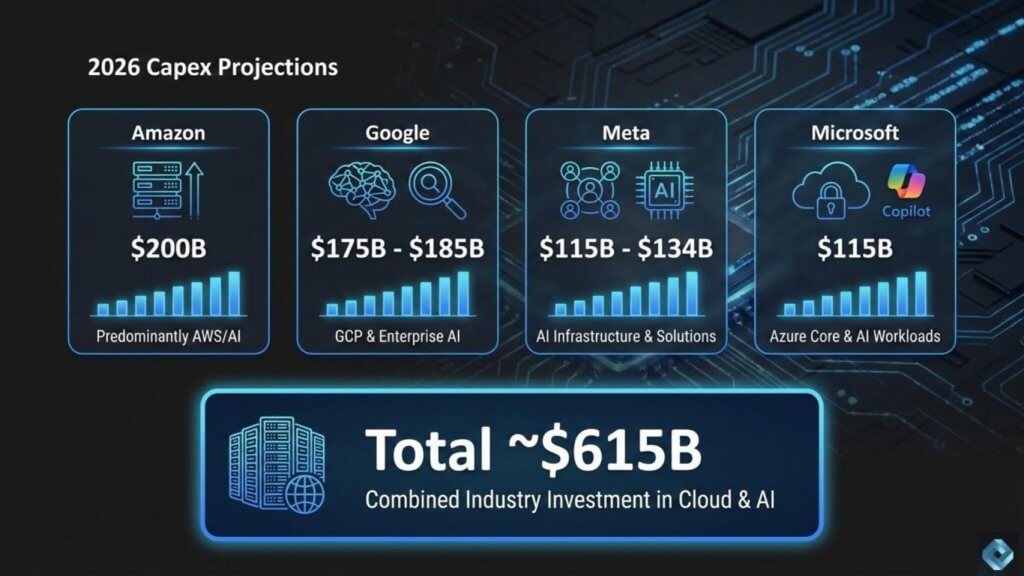

This winter’s 2026 hyperscale earnings prints from Meta Platforms Inc., Microsoft Corp,, Alphabet Inc. and Amazon.com Inc. made it quite clear that capital expenditures are accelerating. Combined, these four firms will spend more than $615 billion in capex this year, an increase of approximately 70% over what was already considered an inflated 2025.

Despite strong fundamental artificial intelligence and general-purpose computing demand, this news caused significant concern for market watchers because the aggressive spending has murky payoffs. Coupled with the Anthropic PBC-infused software-as-a-service attack, investors took stocks down for most of the week, including Nvidia Corp.

Confusingly, much of the capex spend is going to Nvidia – perhaps as much as 60% of the AI portion of the capex will go to that company – a point investors seemed to overlook. Notably, the market bounced back Friday after this week’s earlier rout.

In this Breaking Analysis, we parse through the statements made by company managements on this week’s earnings calls, including what we see as some assumptions that conflict with our scenario for how the AI buildout will evolve. In particular, though operators are understandably focused on paying for Nvidia’s gross margins, we believe observers are underestimating the cost advantages that Nvidia will have relative to graphics processing unit alternatives, including those from Advanced Micro Devices Inc., Intel Corp. and hyperscalers.

The capex story is impossible to ignore. Amazon came out Thursday night after the close with a $200 billion capital expense forecast for the year and the stock was well off Friday on that news, combined with a conservative outlook. Google is right there as well with north of $175 billion for the year. Meta telegraphed a similar hefty appetite for capex earlier. Microsoft increased its capex spend, but Azure growth decelerated sequentially by a point and was below the buyside expectations. That catalyzed a selloff because investors saw a divergence between capex growth and Azure growth and immediately questioned the timing of the payoff.

We believe the market is recalibrating to the scale of what is underway. The numbers are extraordinary. When you add up the big players, we are talking about roughly $615 billion in capex spend in the coming year. Most of that is aimed squarely at cloud and AI. Put that on top of more than $300 billion and change last year and the step-up is more than concerning to observers.

But we see this as a buildout cycle that is being seeded by capital expenditures. The market is trying to answer two questions at the same time: 1) How long does it take for this infrastructure to be stood up, get utilized, translate into revenue and ultimately deliver operating leverage; and 2) How much of the near-term upside is constrained by supply, deployment times and the practical work of integrating AI into products and enterprise workflows.

The Microsoft example underscores the situation as we discussed last week. The company spent more, but Azure growth did not accelerate. Investors expected the two to move together, and when they didn’t, the stock took the hit and the narrative became negative. We believe the same concern is now being applied to Amazon and Google. And yet both Amazon Web Services and Google Cloud accelerated cloud growth. So what that tells is that the burden of proof has shifted from “AI is the future” to “Show me the money.”

Let’s go to management commentary. Microsoft has already been covered in depth last week. The focus here is what Amazon Chief Executive Andy Jassy says about AWS and what CEO Sundar Pichai says about Google, because their explanations will tell us whether this capex surge is building ahead of demand, in response to demand, or simply trying to stay in the race. Hint: We strongly believe it’s all of the above, including securing allocation of the latest and greatest technology from Nvidia.

Net-net is we believe the market is entering a new phase of the AI trade where capex scale is no longer celebrated in isolation. Investors want tighter linkage among infrastructure spend, growth and return.

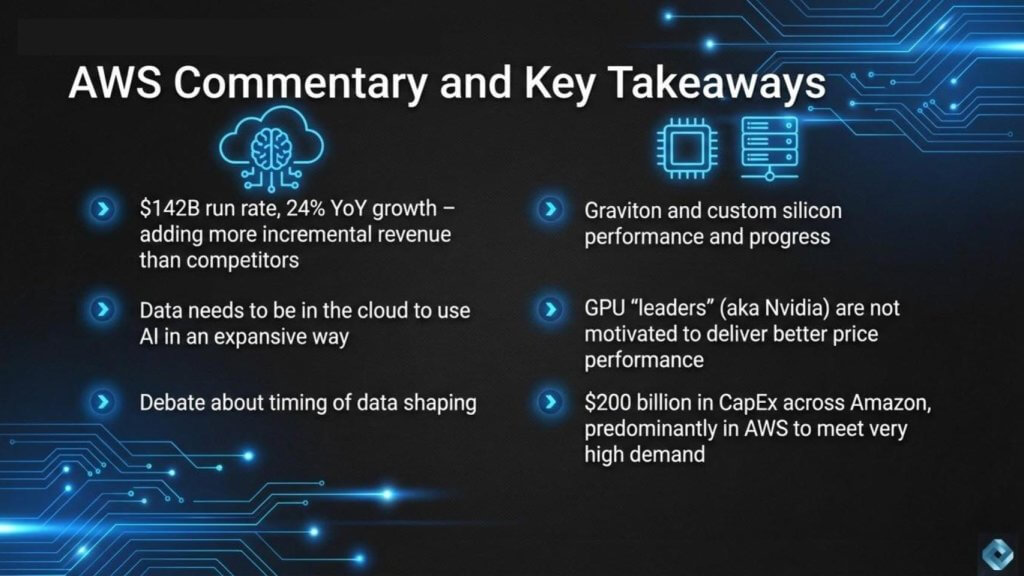

AWS put up a better quarter than expected. At a $142 billion run rate, the business grew 24% year over year. That’s stronger than the 21% to 22% growth range that was in our model. The results set a baseline for how investors interpret the $200 billion capex estimate. If AWS is still growing in the mid-20s at this scale, and possibly accelerating growth, it says the demand is intact. The debate is around where the returns accrue and who controls the unit economics.

Andy Jassy leaned into the “large base effect” argument, saying it is very different to grow 24% on a $142 billion run rate than to grow at a higher percentage on a meaningfully smaller base. He explicitly stated that AWS generated more incremental revenue year over year than competitors. That point applies to most competitors, but it does not apply across the board. Microsoft Azure is not a small base business anymore, and Jassy’s claims about incremental revenue dollars simply does not apply to Azure. Specifically, by our estimates, Microsoft Azure added about $2.5 billion more incremental dollars than AWS in calendar year 2025.

Two other parts of the commentary are important because they reveal how AWS wants the AI story to be understood.

First, Jassy emphasized that expansive AI adoption requires data and applications to be in the cloud. That is a direct attempt to link the AI cycle to cloud migration patterns. The underlying message is that AI is not just another workload. It is a forcing function that pulls data gravity and application placement toward the cloud. Though it’s true that the cloud continues to far outpace the growth of traditional on-premises spending, customers continue to report frustration over cloud costs and all major firms we talk to are experimenting with on-prem AI stacks to balance costs, sovereignty and trust.

Second, he highlighted a shift in how enterprises may want to shape models. The prevailing pattern has been to apply enterprise data late in the lifecycle through fine-tuning and post-training. Jassy said there is a debate and AWS believes enterprises will want models trained on their data earlier, at the pretraining stage if possible. We agree with Jassy and have discussed this in Breaking Analysis.

The top leaders we talk to are not waiting for perfect data conditions. The pattern that shows up repeatedly is that AI helps organizations find what matters in messy data, clean what needs to be cleaned for the outcome, and move faster than the “get your data house in order first” narrative suggests. JPMorgan Chase & Co., Walmart Inc., Dell Technologies Inc., IBM Corp. and AWS itself are all examples of organizations leaning into that approach.

Where the call really gets interesting is silicon.

Jassy described a $10 billion run rate business in silicon and made two key points. The first is that AWS is expanding core compute capacity daily and that most new capacity is running on Graviton. He cited Graviton as up to 40% better price-performance than leading x86 processors and said it is used by over 90% of AWS’ top 1,000 customers. We have written extensively about Graviton and Nitro. Graviton was a direct attack on x86 economics at a time when the x86 performance curve was flattening. Annapurna Labs had an early lead, and AWS exploited that window effectively.

The second point is our interpretation is that AWS is now applying the Graviton playbook to AI accelerators. Jassy argued that inference cost needs to come down for AI to be used expansively, and that a significant impediment is the cost of AI chips. He said customers want better price-performance and that the dominant early leader is not in a hurry to deliver it, which is why AWS built Trainium. He claimed AWS has landed more than 1.4 million Trainium2 chips, described it as the fastest-ramping launch ever, and said Trainium2 is 30% to 40% more price performant than comparable GPUs.

We buy part of that narrative and reject part of it.

Trainium benefits from a supply-demand imbalance. Nvidia cannot satisfy all demand, and any viable alternative will soak up undersupply. That does not diminish AWS’ silicon efforts. But it explains why the ramp is happening in a market where buyers are capacity-constrained.

The part that doesn’t hold up is the suggestion that Nvidia is not driving better price performance. Nvidia is driving aggressive improvements in performance, throughput and cost per token on an annual cadence. The pace off innovation and economics is the lead story. The market is moving fast, and Nvidia is moving faster than anyone else. Despite Jassy’s disclosure of a $10 billion silicon run rate business, Nvidia continues to be the leader with easily 10 times the volume of AWS. This is why we believe the low-cost curve and the supply curve remain tightly linked to Nvidia’s roadmap. AWS can capture meaningful share because the market is enormous and supply is constrained, but competing with x86 is not the same as competing with Nvidia.

That brings us back to capex. AWS is building at a scale that forces hard choices, and the silicon strategy is an attempt to control unit economics and reduce dependence on a single supplier. The question investors are really asking is how quickly that capex converts into sustainable monetization and whether the custom silicon strategy improves margins over time.

The other key point we want to make clear is it is our belief that Nvidia will be the low-cost supplier and operators that cannot secure allocation of the latest and greatest Nvidia technology will fall behind. Whether Trainium, tensor processing units, application-specific integrated circuits or alternatives, Nvidia in our working model will be the most economical solution and lack of access to its technology will hinder competitiveness.

AWS delivered stronger growth than expected, and Jassy used the call to tie AI demand to cloud placement, push the model-shaping debate earlier in the lifecycle, and double down on custom silicon as a unit economics lever. Graviton is a proven playbook. Trainium is the same playbook applied to accelerators in a market defined by Nvidia’s pace and a supply-demand imbalance that creates some room for alternatives. But much of the $200 billion capex number will go to Nvidia because without access to Nvidia technology, operators, including AWS, will fall behind. This all keeps the pressure on execution, but the AWS message is that capacity, silicon and cloud placement are the knobs it can turn that determine who wins the AI infrastructure cycle.

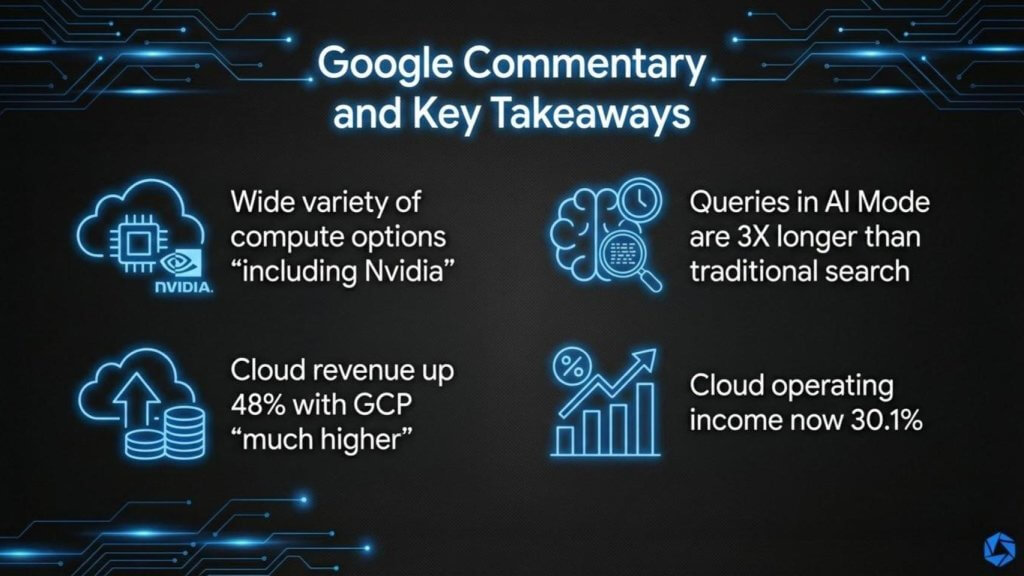

Google’s commentary had a different tone than AWS. The focus was more on the demand behavior and what that implies for Google’s infrastructure roadmap. Sundar Pichai made two points for 2026 that caught our attention. First, Google is expanding compute choice in a way that includes both its own TPUs and Nvidia GPUs – because in our view he absolutely needs the latter; and the same dynamic applies with TPUs as with Trainium, although Google has been at the accelerator game longer. Second, the demand profile for AI-powered search experiences is changing usage patterns in ways that will drive more compute intensity and higher unit costs.

Pichai has now referenced Nvidia multiple times as a key partner. This time, he said, “This includes GPUs from our partner, NVvidia, who announced at CES that we’ll be among the first to offer the latest Vera Rubin GPU platform, plus our own TPUs that we’ve been developing for a decade.” The takeaway is that TPUs are important, but the hyperscalers still need access to Nvidia’s latest platform. To repeat, we believe Nvidia remains the low-cost provider on the leading edge, even for inference, because the cadence and cost-per-token improvements are coming faster than anyone else can match. The insiders understand that if they are not on allocation, they fall behind. That is why the Nvidia callouts keep showing up.

Google’s demand dynamics were equally notable. Pichai said usage (for AI tools) increases once people start using the new experiences. “In the U.S., we saw daily AI queries per user double since the launch and AI overviews continue to perform very well.” He followed that with a tidbit that is relevant for cost structure: “Queries in AI mode are 3X longer than traditional searches,” sessions are “more conversational,” and a meaningful portion of AI mode queries lead to follow-ups. He also said “nearly one in six AI mode queries are now nontext, using voice or images.”

What he didn’t discuss is the cost of AI queries. We believe those metrics describe a fundamentally different workload profile. Traditional search is optimized to fractions of a penny per query. AI mode is orders of magnitude more expensive – perhaps 100X. Longer prompts, follow-ups and multimodal inputs drive higher inference cost per session. That is why cost per token and tokens per watt per dollar have become central metrics across the industry.

The business model tension is embedded in the usage curve. Google’s stock is on a tear and social media is ripping forecasts by talking heads such as Brad Gerstner from six months ago pointing to the demise of Google’s search business at the hands of OpenAI. But this story is not over, in our view, and will play out over the next several years.

This dynamic is showing up in competitive behavior. There is a public marketing battle emerging around ads and consumer positioning (such as the Anthropic Super Bowl ad attacking OpenAI). The strategic question how AI ads are done. The Anthropic ad implies OpenAI will bring a terrible ad experience to its users. But what if it actually reimagines advertising, not as a “blue link” but as a true research-driven experience. This will require a new relationship with both brands and users that Google would have to match. Not that Google couldn’t match the experience; it clearly can. But to Gerstner’s point that he’s getting criticized for today, it’s hard to see how Google’s margins and dominance would be preserved in this new era.

The key issue for OpenAI is whether it can pressure Google’s transition to this new model as AI shifts user behavior toward higher-cost interactions. If Google is forced to defend share while retooling the economics of search, it creates pressure on margins and reinvestment capacity. The risk for the challenger is, of course, focus. Competing across consumer, enterprise, silicon ambitions and multiple distribution fronts at once is a hard execution problem. But in our view, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman’s flip flop on advertising (post the code red) is designed to reduce Google’s ability to address the shift at its own pace.

The most concrete evidence of Google’s current momentum is in cloud. Google reported cloud revenue up 48%, to $17.7 billion, in the quarter, and cloud operating margin rose to 30.1%, up sharply from 17.5% a year ago. Management described the quarter as “outstanding” (we completely agree) and attributed performance to strong demand for enterprise AI products. They also pointed to strength in GCP specifically, noting that GCP continued to grow much faster than overall Google Cloud revenue. Google does not break out GCP revenue directly, but the implication is AI demand is driving infrastructure demand and acceleration in its cloud business. Moreover, the company is finding operating leverage at the same time.

We believe this combination of accelerated growth and improved profitability increases its ability to fund the AI buildout. That buildout still leans on both TPUs and Nvidia GPUs. TPUs help improve economics and help fill supply gaps. Nvidia provides the leading-edge cost curve and performance cadence. In our view, the two are not mutually exclusive. They are complementary in a market where demand is expanding faster than supply. But to be clear, our assumption is that Nvidia will continue to pull away from the TPU and ASIC pack with respect to performance and cost.

Google is showing strong execution in cloud and clear signs of accelerating AI-driven demand, but the economics of AI search are moving toward higher compute intensity per user session. Pichai’s repeatedly emphasized on being early to Nvidia’s Vera Rubin platform, which reinforces our view that hyperscalers still desperately need Nvidia allocation to stay on the lowest-cost curve, even as they push internal silicon. The cloud results suggest Google has momentum and operating leverage, and the next question is how quickly it can translate rising AI usage into sustainable monetization while managing a shift in its core search business that is inherently more expensive.

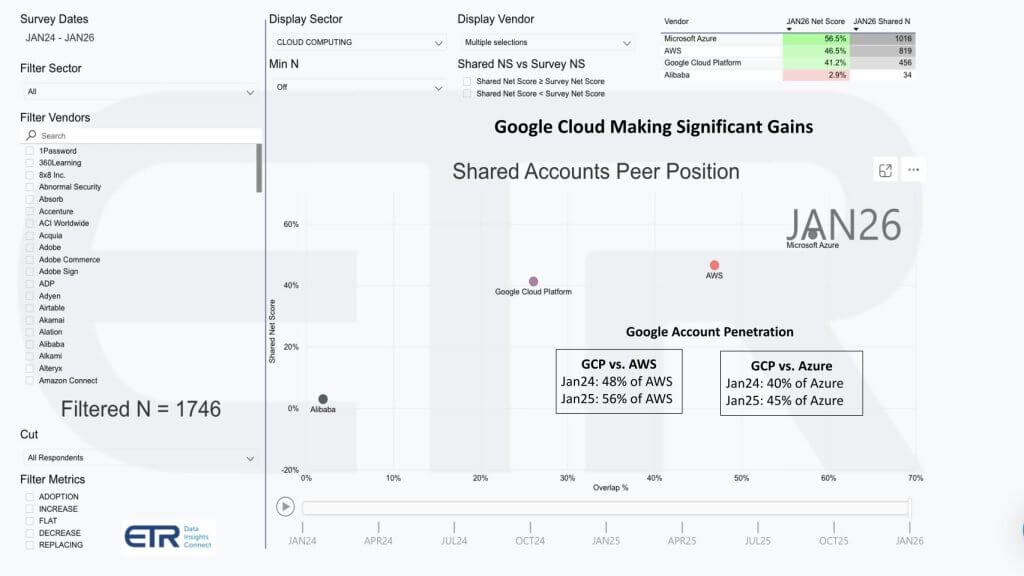

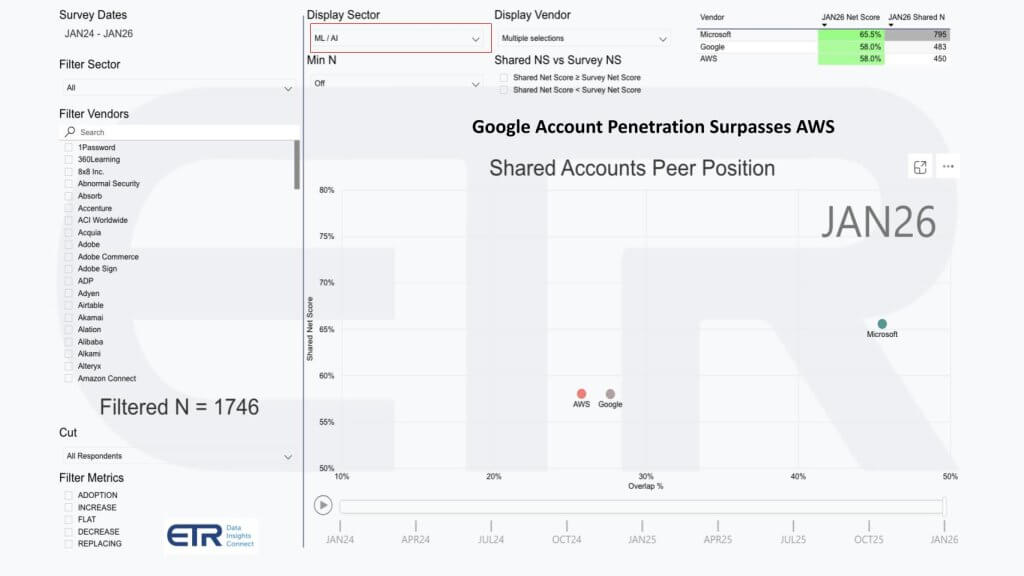

This ETR chart below is one of the cleaner ways to cut through the noise because it is account-based and forward-looking. The dataset is from the January survey with 1,746 accounts. The vertical axis is Enterprise Technology Research’s proprietary Net Score, a proxy for spending momentum. The horizontal axis is overlap, which reflects penetration inside those accounts. The plot shows Azure, AWS, Google Cloud Platform, and Alibaba Cloub. Alibaba has a small shared N of 34, so it is not really the story here.

The first thing to note is that the Big Three are all above the 40% Net Score mark, which we consider highly elevated. Azure is in the upper right and the numbers are exceptional with a roughly 57% Net Score and a shared N of about 1,016. That is what “ubiquitous and still accelerating” looks like.

AWS is also highly elevated with a Net Score around 46.5 and a shared N of roughly 819. The interesting movement is Google. GCP is sitting at roughly 41.2 Net Score with a shared N of about 456, which puts it above the highly elevated threshold while still trailing the top two on account penetration. The question to ask is whether that penetration gap is narrowing. The answer is yes.

The simple way to see it is the relative penetration math we added on the graphic. In January 2024, GCP’s overlap was about 48% of AWS’. In January 2025, that ratio moved to about 56%, using the current shared Ns as the proxy, 456 divided by 819. That is meaningful progress. Against Azure, the ratio also improves, just not as much. GCP is going upmarket, but Azure’s footprint is massive and it is holding its position.

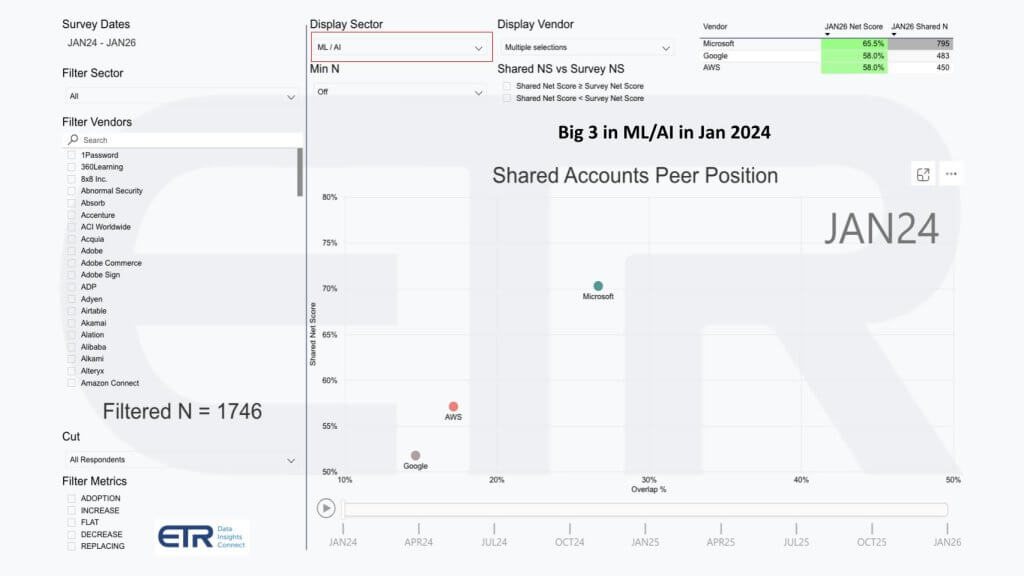

We believe the driver is AI and machine learning, and the follow-on charts below reinforce this. In the ETR data set, for the machine learning and AI sector, Google moves from trailing AWS on overlap (first chart below – Jan 2024) to overtaking it (second graphic – Jan 2026), with comparable spending momentum in the high-50s and Microsoft higher in the mid-60s.

The point is that Google’s AI and machine learning strength and its data platform story are not just creating momentum inside the ML/AI sector. They are creating a tailwind for the overall cloud business, and this cloud sector view shows that tailwind starting to translate into higher enterprise penetration.

The message is that Azure remains the most dominant cloud platform in ETR’s enterprise dataset, AWS is still highly elevated and GCP is gaining penetration at a pace that is now visible in account-level survey data. Google’s strength in machine learning and AI is pulling it forward, and that AI-led momentum is showing up as a meaningful tailwind in the broader cloud sector.

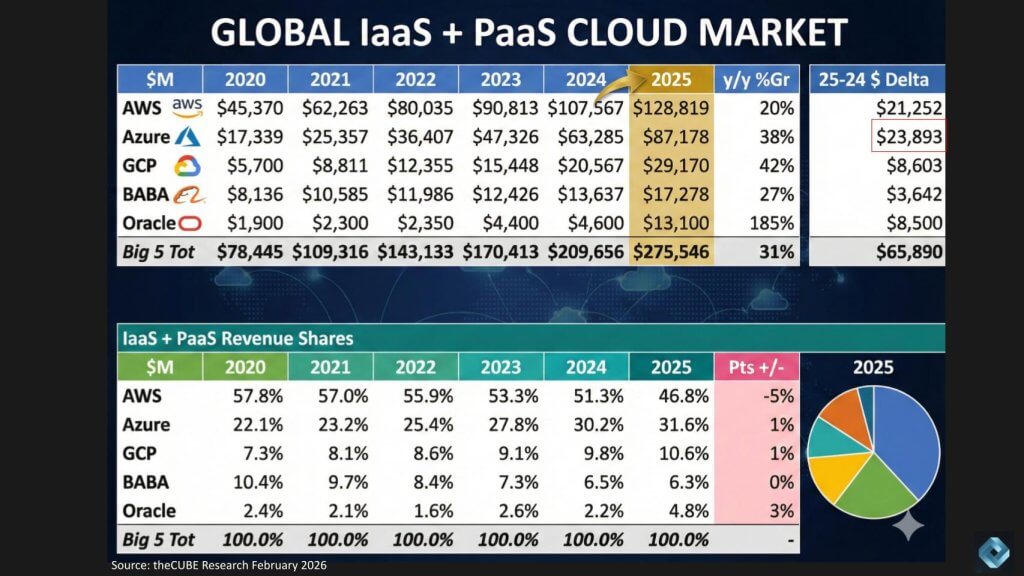

The chart below shows our updated view of global infrastructure-as-a-service and platform-as-a-service revenue market share. We shared a version of this last week and have updated it again for full year 2025. Alibaba and Oracle Corp. still have earnings ahead, so those numbers will get refreshed once the prints come in. Azure is also a moving target because Microsoft reports on a fiscal basis and does not disclose Azure revenue directly, so these are calendar-year estimates based on our triangulation.

The scale of the market remains staggering. AWS comes in at $129 billion in IaaS and PaaS revenue for 2025, and the quarter’s growth rate was 24%. That keeps AWS as the largest player by a wide margin.

The key point, however, is what happens when you look at incremental revenue dollars rather than just growth rates. Jassy said on the call that it is very different to grow 24% on a $142 billion annualized run rate than to grow at a higher percentage on a smaller base, and he went a step further by implying AWS is adding more incremental revenue and extending leadership. That statement holds for many competitors. Jassy’s claim does not hold versus Azure.

On the calendar-year view above, Azure added approximately $23.9 billion in revenue year over year, while AWS added about $21.3 billion. In other words, Azure added more incremental revenue dollars than AWS, directly conflicting with Jassy’s statement. This is relevant because through 2024, AWS could claim “incremental dollars” is an important metric in which AWS leads. It can no longer make that claim.

Nonetheless, AWS remains the scale leader. Azure is taking share and is doing it with a very large base. Note that these are estimates from theCUBE Research as Microsoft does not report clean Azure revenue. But our research shows Azure has made significant progress, which calls into question Jassy’s claim.

Google continues to show meaningful progress and is growing faster than all competitors. We have GCP growing over 50% YoY in Q4, significantly faster than Google Cloud overall. One interesting historical trend to note is that GCP is around $25 billion in annual revenue. You have to go back to 2018 and 2021 to when AWS and Azure were of comparable size respectively. Their growth rates at that time were in the high 40s, whereas GCP by our estimates is in the low 50s.

This supports the broader point that the cloud market remains structurally strong and still expanding at a high rate. We’ll update our 2026 forecast shortly but preliminary data suggests these cloud players will add $75 billion to $100 billion of incremental revenue to the market this year. Moreover, the competitive story at the top of the market is tightening, and the Azure versus AWS delta is now measured both growth and incremental revenue dollars that are too large to hand-wave away or obfuscate in earnings calls.

The bottom line is AWS is still the biggest IaaS and PaaS platform on the planet, but the incremental revenue math shows Azure is not a “meaningfully smaller base” competitor anymore. By our estimates, Azure added more revenue dollars than AWS in 2025, and that is the reality investors need to keep in mind when vendor claims lean too heavily on scale without acknowledging who is gaining faster.

We want to close with several observations. We’ll start with some clips that pulled from the Cisco AI summit held last week. In a sit-down with AWS CEO Matt Garman, Jeetu Patel, president and chief product officer at Cisco, asked some fabulous questions and he was pushing Matt Garman on semiconductor cycles, like time to tape out.

He didn’t use that word “tape-out,” tape-out being the time it takes from shipping the design to TSM or whatever foundry for fabrication.

There are two clips that we’re going to play contiguously and we’ll put the verbatim transcript below.

Watch the discussion between Jeetu Patel and Matt Garman.

The first clip talks about the margin implication of doing your own silicon. The second clip talks about the cycle time of semiconductor design to tape out. We think both are telling and causing us to re-think our assumptions about GPU alternatives, even for inference. Notably, we are less sanguine about the hyperscalers’ ability to keep up with Nvidia.

Jeetu Patel: Do you see the economics of AWS changing where the margin structure gets even better? Because if every application has inference and you’re going to have inference capability in the stack that you have built out, does that improve your margins over time?

Matt Garman: I have no idea, that’s a good question. That’s for the bankers to guess on. But I will say it definitely, I think it improves our margins versus only using Nvidia GPUs. And they’re always going to be a big part of that, but necessarily a big part of that margin goes to Jensen and the team. And we love their products and they execute awesome. But when you have 70%, 80% gross margins, there’s room in there for somebody to take less margin, have a higher-performing part and offer choice to customers.

And so we think that we can offer better price-performance for customers, choice for customers so they can pick between the various options out there, and have the richest set of capabilities that are unique to AWS that they can’t get anywhere else. And that’s part of why we’ve invested in silicon for the last 10-plus years now, and it’s such a big part of what we deliver, which is that differentiated performance all the way down to the silicon layer, which together with our partners, offers a really rich set of capabilities that people can build on.

I think Trainium for us is a huge part of that, whether it ultimately allows us to increase margin or keep margins where they are and lower prices for customers. Frankly, I’d probably bet on the second, because that’s just how data <inaudible> operates –

Jeetu Patel: That’s how it is wired, yeah.

Matt Garman: So my guess is it’s probably more that, which we try to grow faster because we find that every time we lower prices, generally we pass them on to customers and it gives customers more budget to go build new workloads. And for us, that generally leads to a good flywheel.

Jeetu Patel: You continue to make sure that you’re building out the chips. What’s the average cycle time of chips now that you have? Every 18 months you’re getting a new version of the chip out?

Matt Garman: 18 to 24, depends.

Jeetu Patel: And that’s compressing.

Matt Garman: It sometimes is compressing generally, but call it somewhere between 18 to 24 months.

Jeetu Patel: Right.

Matt Garman: But sometimes, you’re also limited on your process generations.

The two clips from the Cisco AI Summit were useful because they put real numbers and real time frames behind the custom silicon narrative. Jeetu Patel tried to pull Matt Garman into the “cycles are compressing” discussion. Garman didn’t take the bait. He stayed with 18 to 24 months, and he added the caveat that process generation constraints still gate the speed at which you can move.

This sets up the obvious comparison that matters most: Nvidia’s cadence is blowing away everyone else’s. That is not to say hyperscalers shouldn’t design their own silicon. It does, however, in our view, underscore that their market opportunity is that which Nvidia can’t fulfill because of supply constraints. As well, we caution that the Graviton playbook relative to x86 will be much harder to replicate against Nvidia.

Finally, we believe for these reasons and the ones on which we elaborate below, that the notion competitors will erode Nvidia’s moat is rubbish.

Nvidia is operating on a 12-month cycle. Vera Rubin was positioned as 5X performance improvement, 10X throughput improvement, and one-10th the cost of the prior generation. That is a step function in a year. Against an 18- to 24-month silicon cycle, hyperscaler roadmaps are not keeping pace. Amazon’s Trainium, Google’s TPUs and Microsoft’s Maia and Cobalt can be meaningful products, but the gap gets bigger if the cycle time stays where Garman put it.

This is also why bringing the Graviton playbook to GPUs is a different animal. Graviton competed against x86 at a time when x86’s performance curve was flattening and AWS had real leverage through system design and integration. Competing with Nvidia is different. Nvidia is not standing still. It is advancing the cost curve aggressively and doing it on an annual cadence. That changes the economics of “alternative silicon” from displacement to a capacity strategy.

That brings up the second point. The suggestion that the dominant leader is not motivated to improve price-performance doesn’t hold water. Customers do want better price performance. Nvidia is delivering it. The cost-per-token improvements are the mainspring of demand expansion, and we expect Jevons Paradox dynamics to drive a 15X demand lift as costs fall and new workloads see continuously improving economics. The irony is the same dynamic that expands the market also increases the supply constraint, and supply constraint is the factor that keeps alternative silicon viable.

We’re not dismissing the supply discussion. In the Garman clip you can hear the constraint around process generations. The foundry system is tight. Nvidia has prioritized access and volume, and volume is everything. Amazon described a roughly $10 billion run rate chip business. Nvidia is operating at roughly a $225 billion run rate. That is a 20X volume advantage. Combine that with faster cadence and deeper ecosystem leverage, and the result is the cost structure and learning curve advantages compound in Nvidia’s favor.

The good news for everyone else is demand still exceeds supply. Everything is sold out. Trainium can be sold. TPUs can be sold. Maia can be sold. Workloads can be identified where those parts are appropriate, and that can persist for a long time because the market is large and the appetite for compute is growing. But the competitive position does not change. If Nvidia remains the dominant volume supplier, it has the lowest-cost curve and the best ability to drive continual cost reduction.

That leaves the edge. The market is right that inference and edge workloads change the topology. Traditional hyperscale regions are often too far away, and we expect “cloudlets” and proximate inference stacks to accelerate, sitting closer to customers and their data. The assumption some make is that Nvidia can’t compete there because it is too expensive. That argument weakened materially with Nvidia’s partnership with Groq. Groq is focused on inference and edge-style deployments, and Nvidia locking up that relationship is strategically significant. Our modeling suggests Nvidia does well at the edge, and this deal addresses a perceived gap in the portfolio.

None of this means hyperscalers abandon their silicon efforts. They probably won’t. TPUs likely have the best leg to stand on because Google has a long runway, tight integration and a clear internal demand profile. AWS is broad enough that it can place silicon across a very wide set of use cases, and Garman’s comment that AWS rarely retires an EC2 instance underscores that they will keep shipping variety and letting customers choose.

The strategic risk is not that hyperscalers build custom silicon. The risk is thinking those programs erode Nvidia’s moat in any meaningful way. They don’t. The moat is maintained in our view because of cadence and volume. And if the hyperscalers are not internalizing that reality, it starts to resemble an IBM OS/2 vs. Windows moment, meaning a technically credible alternative that loses to the dominant platform because ecosystem, execution cadence, and distribution decide the outcome.

Nvidia is the low-cost provider on a faster cycle, and that makes it the reference point for the entire industry. Hyperscaler silicon programs will ship and will sell because the market is supply constrained and demand is exploding, but they are not eroding Nvidia’s moat. The gap will widen when cycle times stay at 18 to 24 months while Nvidia moves on a 12-month cadence with 20 times the volume. The operators that secure Nvidia allocation will stay on the lowest-cost curve. The ones that don’t will be less competitive, regardless of how much custom silicon they build.

That’s our current scenario. Many of you have commented that you disagree with our Nvidia outlook. Please continue to share why as we always appreciate the feedback and debate.

Support our mission to keep content open and free by engaging with theCUBE community. Join theCUBE’s Alumni Trust Network, where technology leaders connect, share intelligence and create opportunities.

Founded by tech visionaries John Furrier and Dave Vellante, SiliconANGLE Media has built a dynamic ecosystem of industry-leading digital media brands that reach 15+ million elite tech professionals. Our new proprietary theCUBE AI Video Cloud is breaking ground in audience interaction, leveraging theCUBEai.com neural network to help technology companies make data-driven decisions and stay at the forefront of industry conversations.